A bibliometric analysis of Australia's public library adult non-fiction collections

Matthew Kelly

Introduction. This paper reports on a study that sought to understand how public librarians in Australia prioritised different types of subject knowledge.

Method. Collection data were sourced from the resources of the Online Computer Library Center (OCLC). These data were filtered by individual library to ensure only adult, English-language and non-fiction monograph titles remained. The collection data linked each title (n=2.9 million) to an OCLC Conspectus category. These data were collated to obtain a set of tiers (groups of categories with similar collection per centages) as well as a ranking of categories at individual library level and as an aggregated collection.

Analysis. Using a qualitative framework developed in a pilot study, the implications of the high preponderance of materials in categories holding one per cent or more of each individual collection was assessed.

Results. All collections had similar structures (tier per centages) and the categories with greatest representation in the sample were replicated in virtually all collections in very similar ways.

Conclusion. Adult non-fiction print and e-book selection is highly skewed towards a small number of categories in Australian public libraries and this is evident at a structural level of analysis, not just the categorical or topical level.

Introduction

This paper reports on an ongoing research project that involves the co-operation of sixty-three Australian public libraries (approximately 10% of all public libraries in the country) and the Online Computer Library Center (OCLC) in Dublin, Ohio. This is the largest bibliometric study, to date, to be conducted in Australia using public library collection data. The aim of the research is to understand the structure of the collections using the current conspectus categories that are used by OCLC in its WorldShare applications. In library terminology, conspectus refers to a subject hierarchy. The category is the intermediate level between subject and division. The concept of structure is used in terms of how diverse the collections are (often referred to as their range) but also relates to how different kinds of knowledge categories coalesce to form ontologies. That librarians have a duty to understand collections, in order to make effective selection decisions and thereby meet users' needs, may seem an unremarkable claim but in a modern management setting, where operational requirements dominate, there is a risk that the practice falls in to desuetude.

Since understanding a given collection seems to be often regarded as an exercise in evaluating moral worth, evaluating utilitarian programmes linked to collection users' demographics, matching demand with supply or even explaining how finite resources are divided up in a pluralistic environment, it seems appropriate to find a way to refigure the setting within which this methodological question is placed. This research is premised on the notion that we can only understand collections when we acknowledge that we already have a valuable history of bibliometric inquiry relating to collection development from which we can take our course (for example, White, 1995, 2008; White and McCain, 1997; White, 2008; White et al., 2009). A basic assumption is made in the research design of this project that, given the relative simplicity of the data analysis process, librarians should try harder to understand the structure of their collections. A secondary assumption is that the user-centred paradigm in collection development has become dominant, not because of any intrinsic value in circulation data, but because most librarians are left unprepared by professional education to engage in a more robust practice, that being elementary bibliometric analytics.

It is necessary to define the term collection structure. The term has made little headway in the collection management literature to date, although it is often used in nondescript ways when collections are being referred to (Baruchson-Arbib and Bronstein, 2002; Bhardwaj and Margam, 2017; Jing and Jin, 2009; Hill, Janee, Dolin, Frew and Larsgaard, 1999; Johnson, 2010; Jones, 2005; Kilarova, 2007; Koenig and Mikeal, 2010; Lee, 2005; Liu, 2017; Lutz and Meadow, 2006; Nikolaidou, Anagnostopoulos and Hatzopoulos, 2005; Parichi and Nisha, 2015; Wagner-Döbler et al., 2003). This research does not attempt to adopt any of the modalities that these authors bring to the term. The term collection structure is used, preparatory to any actual discussion of the sample structure analysed here, in a naturalistic way which simply acknowledges that qualitative and quantitative measures can be superimposed on the classificatory and holdings data.

The term collection profile is preferred in Johnson's (2018) text book and has a subtler meaning than collection structure. Collection profile refers to a type of understanding that can be related to particular collections and is widely used in a vernacular sense to describe unique features of a public library's collection that are generally only known to those involved in managing the collection. Profile in this sense can refer to how the collection is comparatively weighted towards a range of factors: material formats, languages, age of the materials, the ratio of children's material to adult material, the ratio between fiction and non-fiction material, and even reading levels (Ceynowa, 2009; Das, 2002; De Schepper, 2013; Dickey, 2011; Eberhart, 1997; Edem, 2010; Eskett, 2011; Gyeszly and Ismail, 2003; Hawkins, 2010; Henry, Longstaff, and Doris, 2008; Herzog, 2006; Ilik, Storlien and Olivarez, 2014; Intner, 2002a, 2002b; Katsanyi, 1995; Kulisiewicz, 2010; Lihua and Lu, 2006; McGee, 2015; Madsen, 1999; Nash, 2006; Paskoff and Perrault, 1990; Price and Kresh, 2002; Schaffler, 2004; Stellingwerff, 1977; Szasz, 2001; Woodward and Evans, 1984; Yan Lee and Freedman, 2010).

Within this research project the bibliometric data analysed have shown a number of similarities across the sampled collections that warrant discussion on structure. Much else of what is discussed here has a collateral relationship to uncovering (and possibly explaining) how collection structure reveals more about how we treat the concept of knowledge in a public library. While the individual subjects in the sampled collections are interesting waypoints, (certainly interesting for their commonality and difference), it is their structural relationships to each other that serve to reveal insights into how selection decisions can bind and loosen relationships of normalcy, power, knowledge and discourse. What it means to have the responsibility to influence the balance of these relationships, and just how discretion should be exercised, is under-researched at present. What our selection decisions say about us as librarians and as civic actors, and how we negotiate our freedoms and constraints to deliver a view of the world, is discussed in the results of the bibliometric analysis referenced here.

Method

The aim of the research was to understand better an important part of a national public library collection (adult non-fiction monographs) through a sampling process using a subject hierarchy, the OCLC conspectus, in order to reveal priorities in terms of subject selection.

The Online Computer Library Center conspectus as a bibliometric tool: methodological considerations

The Online Computer Library Center was approached for assistance in facilitating access to their union catalogue holdings data. These data are uploaded by individual libraries to national portals, such as Libraries Australia, and used for national purposes (such as the Australian National Bibliographic Database) and is forwarded to OCLC for inclusion in its union catalogue. Sixty-five Australian public libraries were recruited as anonymous participants in the study over a period of twelve months (2014-2015). The data from two libraries were found to be insufficient for comparison (which was conducted on the remaining sixty-three). All libraries had had a history of active engagement with the Libraries Australia and OCLC catalogue records system. Twenty-eight per cent of the libraries surveyed were regional and 72% were based in a state capital city. Population figures show 81% of the population resident in capital cities (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2018a).

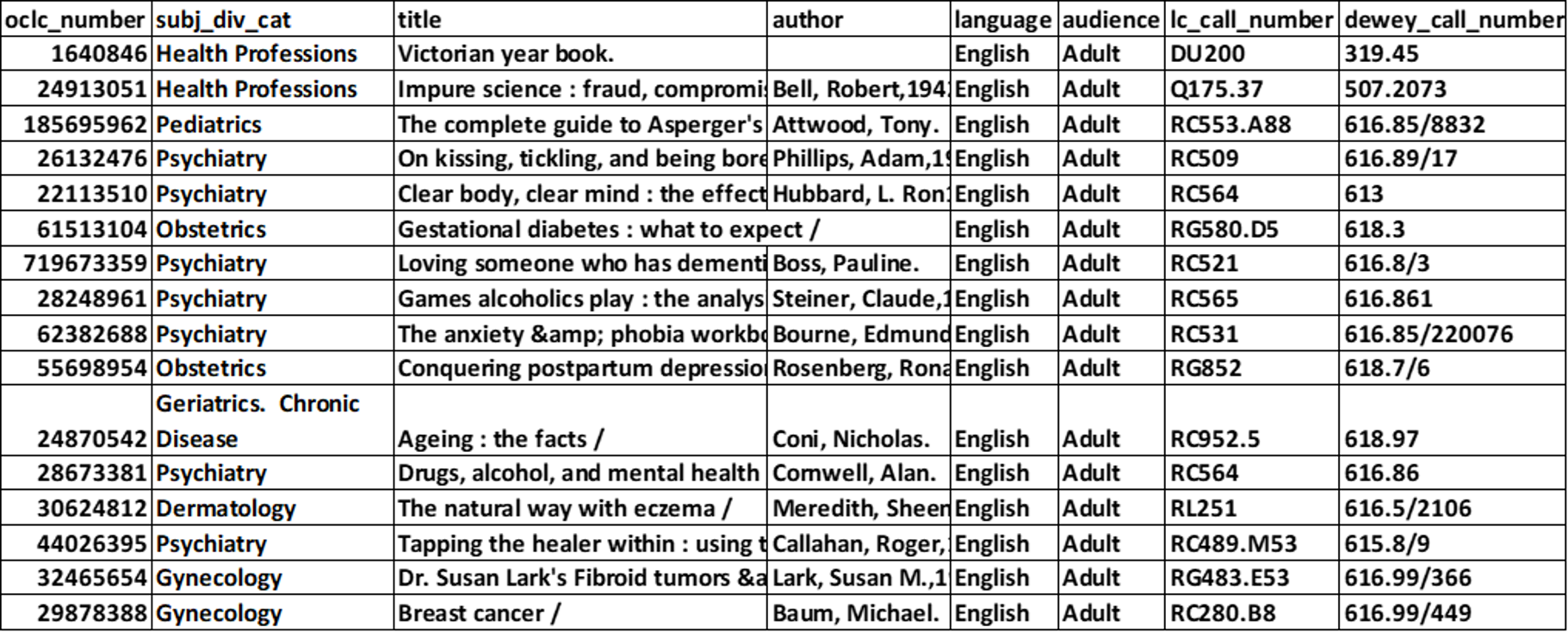

OCLC provided customised records of the research partner libraries' collection records in support of the research. The spreadsheet format of the download is shown in Figure 1. The aim was to filter these data to be able to tabulate the numbers of titles in each subject category. An outline of the data analysed after filtering out non-relevant material (audio-visual material, fiction, juvenile and non-English language works) is below:

- Total titles: 2,945,912

- Library collections sampled: 63

- Mean number of sampled titles per library: 46,760

- Range of sampled titles per library: 8,166-155,666

- The range of category holdings were 329 through to 467 or 67% through to 91% of the possible 512 categories.

Figure 1: Example of spreadsheet data provided by OCLC (column formatted)

SPSS statistical software was used to analyse the spreadsheet data because spreadsheet software was not capable of handling the large number of data lines. Titles were counted in each library so there is significant replication of individual titles in the sample. The point of the research is not to delineate title data but only to show how titles, as representatives of broader subject categories, impact upon the topicality of collections. The OCLC conspectus allows a collection to be broken down into thirty-one divisions (the broadest categories of knowledge), 512 categories (a secondary division) and 7695 subjects (the most detailed description of a topic). The thirty-one OCLC conspectus divisions are reproduced in Appendix 1.

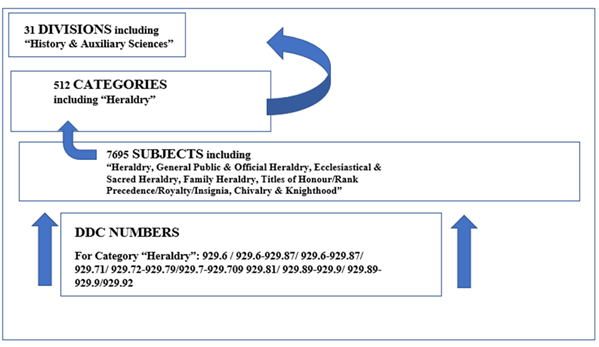

The 512 categories are the subject of this research and fit within a tripartite arrangement as follows, using the example of the category Heraldry in Figure 2. The randomly selected sample category, Heraldry, is defined as a sub-division of the History and auxiliary sciences division. In turn, Heraldry is divided into subjects that interpolate into the category (as the category does into the division): Heraldry, General public & official heraldry, Ecclesiastical & sacred heraldry, Family heraldry, Titles of honour/rank precedence/royalty/insignia, Chivalry & knighthood.

Figure 2: Relationships of OCLC conspectus divisions to OCLC categories, OCLC subjects and Dewey Decimal Classification

Each subject has a higher domain category and each category a higher domain division. We can see with the category Heraldry that it has a subject with the same name as well. This reflects the specific treatment of heraldry as a topic in its own right as well as the need to use the term as a broader descriptor. In Figure 2, it is also possible to see a graphic representation of how in this research Dewey Decimal Classification numbers associated with heraldry are linked with the subjects delineated as heraldry and which in turn constitute the category of heraldry.

The research discussed here sought to obtain a better understanding of what topics are prioritised in Australian public library adult non-fiction collections. The conspectus divisions are too general in nature to provide illumination of the problem. Similarly, the detail involved in utilising conspectus subjects would create a fairly confusing plethora of topics for analysis. The conspectus categories are at the right level of generality to enable comparison to be made and specific enough to promote meaningful ontological analysis. In Appendix 2, the relationship between divisions, categories and subjects can be seen with reference to the five most highly represented categories in the research sample.

Development of the collection tier concept: making sense of subject scattering

A pilot study of eight libraries was undertaken in 2015. The results of this study (Kelly, 2015) were reported as revealing (i) a marked tendency for a small percentage of subject categories to constitute a large proportion of the potential topicality that might have been represented in these types of collections; (ii) distribution of the aggregated collection conformed to a power law distribution (80/20) so that approximately 80% of the collection was represented by 20% of the subject categories (where Trueswell (1969) found 80% of circulation was met by 20% of titles, this research shows that 80% of titles are found in 20% of conspectus categories); (iii) there were significant commonalities in the types of subject categories that were found in the designated tiers and that it may be possible to develop ontologies that correspond to the collection tiers.

Collection tiers are analogous to the zones identified by Bradford (1934), although the concepts differ in that Bradford zones are constructed as ranking, in a collection, small numbers of productive journals and their associated large number of publications, whereas the collection tiers in this study use fixed percentages of the sample libraries' collection that are not directly correlated with usage output. The collection tiers were constructed from approximately 25,000 data points (each one, one of the 512 conspectus categories) and the significance of how to interpret the sixty-three sets of data that constituted the sample required a well-articulated and cogent approach to scattering. Hood and Wilson (2001b) discuss Hjørland's (2001) notion of scattering (which he credits to discussions inspired by their paper ‘The scatter of documents over databases in different subject domains: How many databases are needed?' [Hood and Wilson, 2001a])

Hjørland (2001) suggests that at a deeper and more theoretical level, scattering among databases is related to different kinds of scattering within the journal articles. He proposes three types of scatter: lexical scatter or the scatter of one word (as in his search #4 Shakespeare); semantic scatter or the scatter of one concept with different synonyms (as in his search #10 dark matter) and subject scatter or the scatter of concepts useful to a problem (as in his search #9 hair loss). The gradation of scatter is from simple to complex, with lexical scatter being the most objective and subject scatter the most problematic, requiring a comprehensive search formulation. Furthermore, the degree of semantic and subject scatter may be important indicators of interdisciplinarity. A logical progression of this research is to investigate further the underlying mechanisms for the types of literature scatter so as to answer suggested questions, such as: ‘To what degree is the overlap caused by overlap in the indexing of the same journals in different databases?' and ‘To what degree does overlapping terminology and concepts in different fields cause the overlap?' (Hood and Wilson, 2001b, 1253-1254).

In a later work, Hjørland and Nicolaisen (2005) attempt to disentangle Zipf¨s law as it relates to lexical scattering (the ‘number of occurrences of a given word in a long stretch of text is the reciprocal of the order of frequency of occurrence' (p. 102)) from semantic scattering where domain classifications come up against synonymous or rival interpretation. There is also the intention to disentangle both of these from subject scattering which Hjørland and Nicolaisen see as key to Bradford's law; it is domain analytical in its approach (and hence ‘task-useful') and already ‘determined by given theories in the subject field' (p. 104) with associated implications for how we deploy and interpret relevance. Hjørland and Nicolaisen make the observation that citation patterns are one important way to better understand ‘subject relations as relations of relevance or usefulness' (p. 104). This subject scattering, while it has some connection with lexical scattering, is more useful when combined with semantic scattering approaches; this helps to ease the difficulty of making ‘operational implications of "subjects"'. What makes a subject is variable for us ontologically but we also need to ‘generalise views about subjects' and this, as a result, opens debate within epistemological contexts.

Hjørland and Nicolaisen (2005) believe that at least one implication of this move towards an epistemologically informed approach to our view of subjects is that ‘a pure mechanical view of selection must consequently be replaced by a reflective view in which the selector must justify the selection on axiological arguments' (p. 104). Hjørland and Nicolaisen (p. 100) reveal the assumptions associated with the unity of the sciences approach that Bradford links with the distribution of references. Bradford's self-declared unity of the sciences approach has significant potential when understood in the context of how a concept such as scattering might be connected to, say, interdisciplinarity (the greater the interdisciplinarity the greater the scattering). Distribution of scattering is similarly related to how we designate borders to subject fields (or just subjects).

The pilot study helped to determine a rigorous methodological approach to looking at collections based on a category's percentage of titles in relation to the collection sample. Categories could be aggregated as tiers of the collection based on their percentage of the (sampled) collection. These were delineated based on the data (nothing was over 10%, most everything was under 1%, so a mixture of simple fractions such as halves, quarters and tenths were chosen) for ease of manipulation. While there are five tiers in this system, four, six or ten could easily have been chosen. Some method of structuring the percentage of the total collection was needed to gain perspective on the categories (what was being collected and in what quantities), especially as they formed aggregated sets (within and between collections). The tiers from the pilot study were carried over to the present study and are as follows:

- 1% or more of the sample – Tier 1

- 0.5% - 1% of the sample – Tier 2

- 0.25% - 0.5% of the sample – Tier 3

- 0.1% - 0.25% of the sample – Tier 4

- 0.1% or less of the sample – Tier 5

Analysis and results

Structural analysis

Two sets of analysis are presented here. The first (analysis by tier) involves looking at the results with the sixty-three collections unaggregated (categories are left in situ) and compared using analysis of each library's set of tier percentages which are then compared for the mean. The mean is then used as the basis of comparison. In the second analysis (by aggregated OCLC conspectus categories) each of the sixty-three sample collection's category percentages are added together to form an aggregated analysis. The aggregation of the collection analyses allows for comparison to be made with the pilot study, which also used this method, and allows for:

- a comparison to be made as to whether aggregating the collection category percentages (which does not account for size of each collection sampled) makes any significant difference in the results;

- an aggregated ranked set of categories from which to develop further qualitative inquiry (this method prioritises data collection with reference to the categories, which allows for a range of engagements at the domain analytic level to be considered, while the former tier method does not record category names).

In Table 1 (analysis by tier) an outline of some of the more significant structural results of the research is reported. Each of the sixty-three library collections was split into tiers based upon the percentage of each collection as a proportion of their entire sampled collection. The average percentage of each sampled collection by tier was obtained for all five tiers. The range of categories represented in each tier was tallied and an average calculated from which the data were normalised from Tiers 1 through 5 (average minus prior tier average: Tier 1, 23-0, Tier 2, 47-23 and so on). The normalised average number of categories per tier was divided into sample collections' average percentage of collection by tier to get the Sample collections' average category percentage of collection by tier by normalised average number of categories per tier.

In plain language, this is the average proportion a category in a tier has of the entire collection based on aggregating each sample collection's tier data and dividing this by a set number of categories. For example, in Tier 1 the average of all sixty-three Tier 1s was 49.68%. This tier average is divided by the normalised average number of categories per tier. The range of tiers for each of the sixty-three sample collections was calculated. In Tier 1 there are no earlier data to impact upon the average number of categories so the average number of tiers is used without modification. Note that what is represented in Table 1 on the Tier 1 line in the last column is the Sample collections' average category percentage of collection by tier (49.68) divided by the Normalised average number of categories per tier (23) to generate the resulting Tier 1 measure (2.17).

For the four remaining tiers the same process is undertaken except that an average is calculated for the Range of categories represented in each tier and the previous tier's Normalised average number of categories per tier is subtracted from that to provide a more accurate basis for comparison. It is worth noting how this method of normalising average number of categories per tier leads to a Sample collections' average category percentage of collection by tier by normalised average number of categories (Table 1) which is highly correlative with both the 2018 and 2015 data in Table 2 (Tier average category percentage). Based on the analysis undertaken here we are of the view that it is possible to be 95% confident that the identified structural tier averages for this type of collection in Australian public libraries (adult non-fiction monographs) fall within a reasonably narrow range (about 1% or less). These averages are reported in Table 1.

| Tier | Sample collections' average percentage of collection by tier | St. dev. | Confidence interval (95%) | Range of categories represented in each tier | Normalised average number of categories per tier | Sample collections' average category percentage of collection by tier by normalised average number of categories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 49.68% | 0.03 | 48.94-50.42 | 1-27 | (23-0) = 23 | 2.17% |

| 2 | 15.99% | 0.02 | 15.49-16.48 | 18-56 | (47-23) = 24 | 0.66% |

| 3 | 14.68% | 0.02 | 14.15-15.22 | 42-101 | (89-47) = 42 | 0.35% |

| 4 | 11.57% | 0.02 | 11.27-11.87 | 71-193 | (163-89) = 74 | 0.14% |

| 5 | 7.93% | 0.01 | 7.69-8.18 | 194-468 | (421-163) = 258 | 0.03% |

| Note. The round off error for Sample collections' average percentage of collection by tier is 0.05. n is the number of sample collections used for the analysis. | ||||||

In Table 2 (Analysis by aggregated OCLC conspectus categories), the Average tier percentage of sampled collections by aggregated OCLC conspectus categories (all the sampled library collection categories are added together to make a single collection) are measured and averaged to create a new set of tiers. The difference between the tier percentage data in this analysis and that in Table 1 can be accounted for in terms of categories at the borders, with other tiers' ranked category positions impacted in a different statistical manner when the sample collections' categories are added together. While the Table 2 measure, as indicated above, does not take into consideration overall sample collection size it seems to represent category size somewhat better. Where libraries have collected significant percentages of their collection (at the level of the tier) in a particular category this category will be bolstered in its representation in a tier, with the reverse also being the case. The aggregated analysis saw approximately 1.5% of the sampled collections by tier move from Tiers 1 and 2 to Tiers 4 and 5, with Tier 3 remaining essentially unaffected by the change in analytical method.

| Tier | Average tier percentage of sampled collections by aggregated OCLC conspectus categories | Average tier percentage of sampled collections by aggregated OCLC conspectus categories 2015 pilot results | Tier average category percentage | Tier average category percentage standard deviation | Tier average category percentage confidence interval (95%) | Tier average category percentage 2015 pilot results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 48.68% | 48.15% | 2.03% | 0.01 | 1.58-2.47 | 1.92% |

| 2 | 15.03% | 12.09% | 0.68% | 0.00 | 0.62-0.75 | 0.71% |

| 3 | 15.37% | 20.5% | 0.35% | 0.00 | 0.33-0.37 | 0.35% |

| 4 | 12.22% | 11.33% | 0.16% | 0.00 | 0.15-0.17 | 0.15% |

| 5 | 8.70% | 7.93% | 0.03% | 0.00 | 0.02-0.03 | 0.03% |

| Note: n is the number of sample collections used for the aggregated collection analysis. | ||||||

When compared to the pilot study data, which used the same method of aggregated category analysis, the results were similar with the largest difference being the three and a half percentage points' growth in Tier 2 in 2018 while Tier 3 lost five and a half percentage points in 2018. While these were significant changes (25% readjustments on the pilot study's data) the readjustments seem to be tier exchanges at the margins; it seems likely that the bulk of the fifty-five library collections (which when combined with the eight libraries surveyed in the pilot made up the 2018 study) had a tendency to hold categories which had collection percentages in the 0.5-1% tier rather than the 0.25-0.5% tier range (which correlates to smaller ranges of categories with larger overall percentages of the collection). The tier average category percentages remained consistent from the pilot study through to the 2018 study with the average percentage in each tier only changing by between 0.01-0.11%.

Growth in number of categories per tier was noticeable as more libraries were added to the sampling process. When the 2018 analysis is measured against the pilot study, Tier 1 dropped 1 category (-4%), Tier 2 added 6 (+35%) new categories, Tier 3 lost 16 (-27%) while Tier 4 added five (+6%) and Tier 5 added 64 (+24%). These changes would seem to be consistent with adding significantly more data (nearly eight times greater). Of interest is how the total number of extra categories added is only 59 (+22%) or the equivalent of 11% of possible categories (OCLC categories, n=512). The amount of data added between the pilot study and this study was very large (8.6 times as much) but the number of categories added was only 11%. We are not seeing categories grow at any type of commensurate or consistent rate, regardless of how many collections we add to our sample.

The number of categories per tier in the aggregated category analysis saw decreases in Tier 1 (from 25 to 24) and Tier 3 (from 58 to 44) while Tier 2 increased (17 to 22), Tier 4 increased (73 to 78) and Tier 5 increased (264 to 327). In a similar way to the data reported in Table 1, based on the analysis undertaken here we are of the view that it is also possible here to be 95% confident that the identified aggregated category tier averages for this type of collection in Australian public libraries (adult non-fiction monographs) fall within a very narrow range (while it is about 1% for Tier 1 it is statistically insignificant for the other tiers).

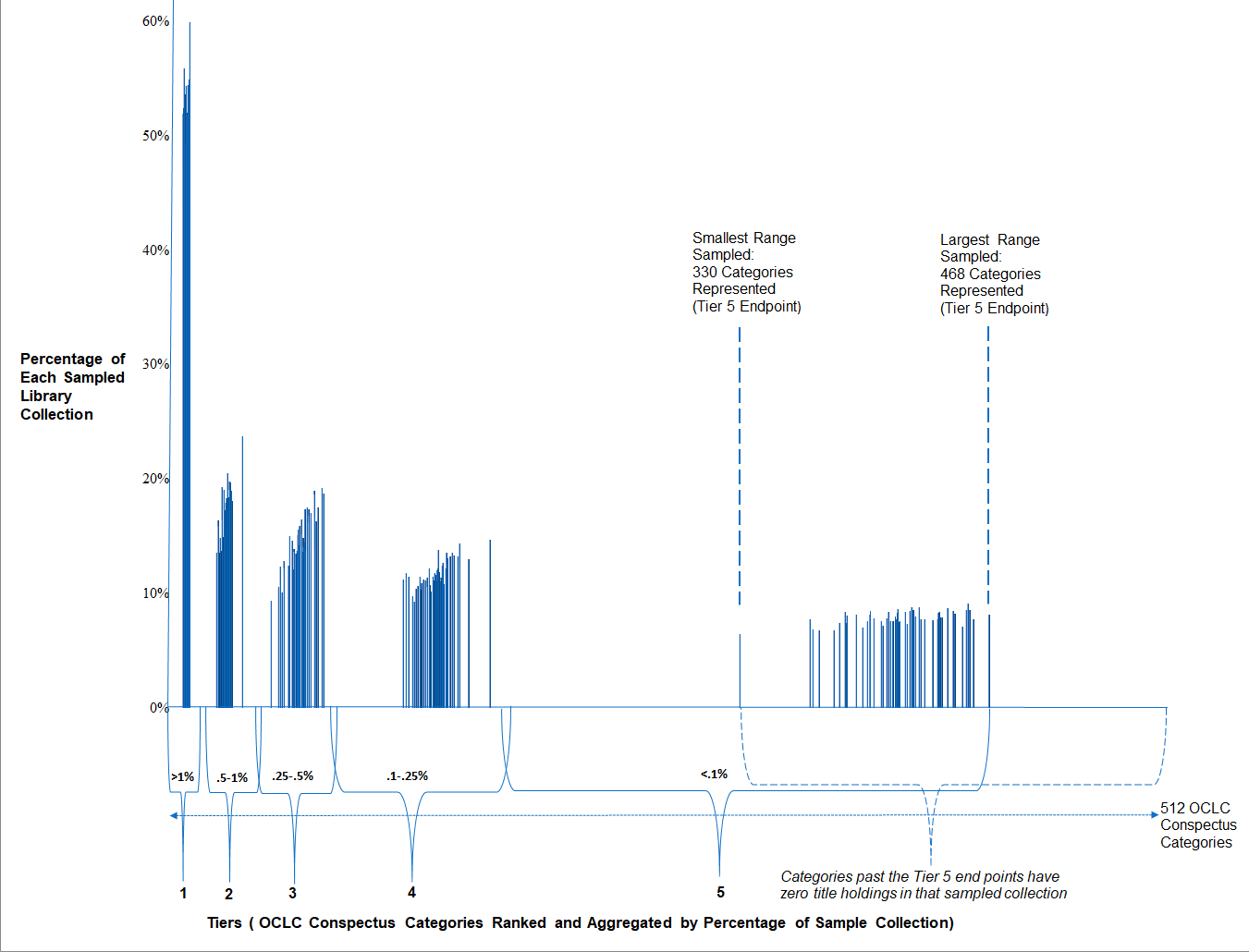

In Figure 3 it is possible to see how each collection is represented in each tier (the data are the 2018 tier mean analysis reported in Table 1). As was indicated earlier, category names were filtered out of the individual collection data sets and what remained for analysis was only the ranked percentages of each individual sample collection. These ranked categories in the tiers were now, in a sense, placeholders to facilitate structural analysis, the ranked positions and percentages in the tier being of interest. As outlined above, these were then aggregated (within each sample collection tier) and tier means were obtained for each sample library collection (at each of the five tier points) which is what is displayed in Figure 3. Figure 3 helps to clarify how all of the sample libraries' Tier 1 representations are within an extremely narrow band of categories (on the x axis). These become progressively broader from Tiers 2-5 for all sampled library collections (representing greater diversity in categories selected but also reduced title numbers selected per category). The chart also gives an indication of how many categories are in the tier. The further along the x axis a sampled collection tier endpoint appears, the greater the number of categories represented for that sampled library's collection. While the clustering that occurs in Tiers 1 and 2 is most pronounced, the chart also shows the significant clustering of sampled collections in Tiers 3, 4 and 5.

Figure 3: Aggregated collection tiers as a percentage of each sampled collection (n=63)

As Table 2 helps to make clear, the average number of categories for Tier 1 is 24. Tier 2 is highly clustered like Tier 1 with far less representation in each category, up to three times less than Tier 1 by virtue of the number of categories represented. This sample indicates that monograph materials (when reduced to categories) in Tier 1 are approximately sixty times more likely to be held in an Australian public library than their counterparts in Tier 5 (see Table 1: Sample collections' average category percentage of collection by tier by normalised average number of categories per tier).

It is important to remember that in this modelling:

- A title is assigned a conspectus category as a result of its classification number

- All titles in that conspectus category are tallied and then the conspectus category is assigned a percentage based on its relationship to the total number of titles (the collection)

- All conspectus categories' percentages are added together so as to form a collection tier (1% and above, 0.5% to 1% and so on)

- The titles and the conspectus categories are not important at this stage. What is sought is a breakdown of each individual collection in terms of these structural tiers, and also, the opportunity to identify similarities and differences.

What we see is significant uniformity in the sixty-three sampled collections in terms of how all collections had prominent Tier 1 representation making up about half of all titles they held in their individual libraries. Tiers 2, 3, 4 had similar ranges of percentage for each individual collection for the categories represented within them (15.99%, 14.68%, 11.57%). Tiers 2, 3 and 4 hold similar proportions for each individual collection (albeit representing almost a doubling of categories represented per tier as we move down the tiers). Tier 5 has a large number of categories (on average about two-thirds of all possible categories) and each category represents a small number of titles held in an individual library. The range in which sampled collections held categories in Tier 5 was much larger than in any other tier; the smallest number of categories held across all tiers was 330 while the largest was 468 (see also, Oliphant and Shiri, 2017). There is noticeable clustering in terms of how each library's Tier 5 percentage of sampled collection was very similar with little deviation from the mean.

Category analysis

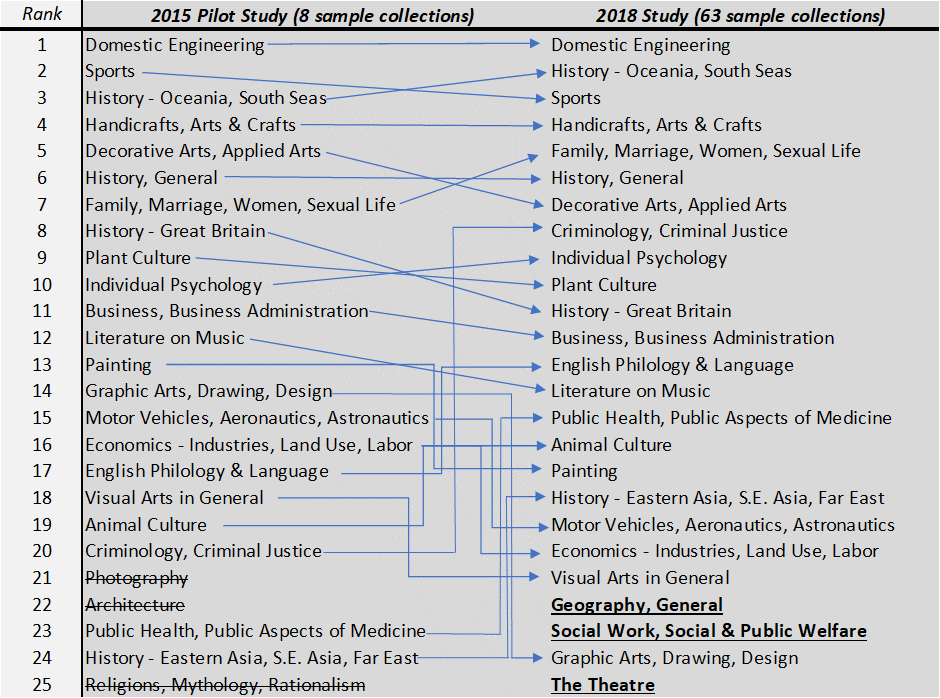

While the structural analysis of the collections is considered to be the most important innovation reported here, especially in terms of the degree of similarity displayed by the sample collections studied, there remains the important factor relating to categories as means to express topicality at a broad, intermediate level suitable for a civil society knowledge setting. By tracking their degree of representation within each collection and in an aggregated form, we are able to gain a better understanding of how particular categories express their importance to library collections (and, of course, implicitly to librarians and users). As can be seen in Figure 4, the ranking of the top seven categories remained very consistent with the pilot study results. All of the top twenty categories in the pilot study retained their place in the top twenty categories in the 2018 study. Three topics represented as Tier 1 in the pilot, (i) Photography, (ii) Architecture and (iii) Religions, mythology, rationalism dropped back to Tier 2 in the 2018 study while (i) Geography, general, (ii) Social work, social & public welfare and (iii) The theatre took their place in the top twenty-five categories.

Figure 4: Category rankings 2015 and 2018 (aggregated sample collections)

The pilot study (reported in Kelly (2015)) identified the difficulty of aligning a collection to meet universal needs and that bibliometric analysis of this sort should not be driven by conventional user-focused concerns. It made explicit how studies of this sort can never be more than the sum of knowledge aggregated by the non-fiction publishing industry over a given period of time. It was possible, even with the small scale of the pilot sample to begin to understand how, at least in the Australian context, ‘subject category priority… in the practical arts of domestic life or the generalisable narrative of history' (p. 9) is prioritised. While the study was a very small sample, the similarity of the sampled collections helped to make it possible to begin to advance the view that some ‘domains are more specifically articulated as knowledge that defines…the types of knowledge that civil society demands and deserves in its libraries' (p. 9) and that ‘the types of knowledge that we do maintain in civil society libraries reflect the epistemic priorities that we set' (pp. 9-10) rather than being selected in unsystematic ways or reflecting knowledge simply as a scientific construct. The thematic designations identified in the pilot study (p. 9) as possible tier ontologies were as follows:

- Tier 1: The self: home and family

- Tier 2: Outside of the self: the civilised mind

- Tier 3: Onward the Enlightenment: specialised science, history and culture

- Tier 4: Democratising knowledge: the world of generalities

- Tier 5: Deep natural and social science: the borders of academic knowledge

While no further work has been conducted to date on assessing whether these ontologies are valid, the similarity of the Tier 1 categories in the 2018 results to those in the pilot study, and the proportion of the sample collections which they represent, makes it possible to say with a degree of confidence that Australian public libraries do have a significant focus in their non-fiction monograph collections on topics that address a user's sense of self and link closely with their experience of home and family. For example, the top seven categories, Domestic engineering; History–Oceania, South Seas; Sports; Handicrafts, arts and crafts; Family, marriage, women, sexual life; History, general; Decorative arts, applied arts all have a focus on what is of parochial concern. Many of these categories can be seen as hobbies as well as related to the duties of managing a home. The history topics relate to parochial history (while the category indicates Oceania and the South Seas, it is predominantly Australian history in the sample collections) and the history of twentieth century wars Australians have participated in. History is present in such a prominent way it would seem, not for its own sake, but as part of its ability to reflect or reinforce aspects of personal identity. History-Great Britain is also prominent in Tier 1. This is not surprising as not only are there significant cultural ties to the United Kingdom (with the majority of Australians tracing their family origins there within the past 200 years) but 5% of the Australian population at the time of the study (approximately 1 million people) was born in the United Kingdom and emigrated to Australia (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2018b).

It is possible to sort the remaining categories in Tier 1 around the themes of self-actualisation or the management of home and family:

- Criminology, criminal justice: understanding criminal behaviour to facilitate personal/family safety or the hobby of reading true crime.

- Individual psychology: understanding mental health for self or family.

- Plant culture: hobbies or growing foodstuffs for self or family.

- History–Great Britain: parochial interest in history, history of one's family.

- Business, business administration: how to run a business to support oneself and one's family.

- English philology and language: this category is largely composed of readers to help migrants learn English.

- Literature on music: this category is largely associated with musical entertainers and relates to ‘personal entertainment'.

- Public health, public aspects of medicine: maintaining the health of self and family.

- Animal culture: keeping pets as a hobby.

- Painting: painting as a hobby but also fine art as entertainment.

- History–Eastern Asia, S.E. Asia, Far East: Australia has a large population originating from Asia and was involved in four wars there in the late twentieth century. It is also a major tourist destination.

- Motor vehicles, aeronautics, astronautics: this category is largely about do-it- yourself motor mechanics which is both a hobby and a part of household management.

- Economics–industries, land use, labour: the works held in this category are mostly about management leadership and business development and relate to how to be personally successful.

- Visual arts in general: fine art and art history as a hobby.

- Geography, general: these works are mostly about exploration and travel as a hobby.

- Social work, social and public welfare: these works are about parenting, the elderly, dealing with addiction and delinquency.

- Graphic arts, drawing, design: graphic arts as a hobby or a profession.

- The theatre: theatre as entertainment, actors' biographies.

In the 2018 study the top seven categories accounted for a quarter of all titles held in the sixty-three collections sampled with the remaining eighteen above rounding out just short of half of the sampled collections' holdings. It would seem that, even just on a prima facie analysis of the state of the collections sampled here, it is evident that there is a significant over-representation of non-fiction adult monographs in narrow category bands in Australian public libraries when five per centof the potential topicality makes up half of the sampled collections. Given this state of affairs, it is worth re-emphasising that with some exceptions, such as Howard White in the bibliometric realm and Birger Hjørland in refocusing our information science theory back to the domain, collection priorities are ‘rarely interrogated for what they represent about our critical or hermeneutic assumptions' (Kelly, 2015, p. 10).

Implications for sociology of knowledge

For more than fifty years the relationship between information science and other disciplines in the social sciences has been an interesting case study in interdisciplinarity, with periods of aloofness (Wilson, 1980) and co-operation (Larivière, Sugimoto and Cronin, 2012; Odell and Gabbard, 2008) being chronicled. While this study is primarily directed at the information science community, it is hoped that the results may also help stimulate interest in how bibliometric methods can supplement inquiry in the sociology of knowledge. Among the potential topics of interest to those outside the information disciplines include the relationships between collections and knowledge, how collection planning has sociological and philosophical implications, and the cultural differences which impact upon selection for civil society readers (with an array of possible factors being considered ranging from the historical and the gendered to the geopolitical and economic).

It would seem straightforward to advance the view that, at least at the level of national history, how Australia's public libraries select from diverse sources will differ somewhat from other Anglophone societies, but to what degree are collection structures and category selection similar? Questions arise about how topically similar Australian public library collections are to:

- those in the USA, UK, Canada or New Zealand (countries that are culturally and linguistically similar);

- those in continental Europe (countries that are culturally similar but linguistically different); or

- those in affluent East Asian democracies such as Singapore, Japan or Korea (countries that, historically, have been culturally different, are linguistically different but economically are similar).

The questions are worth considering for what is revealed in terms of the knowledge base deemed appropriate for civil society readers. Similarly, differences in how knowledge is portrayed for civil society (when the broader social context is a liberal democracy, an illiberal democracy or an authoritarian society) are of interest for scholars both inside and outside the information discipline. There are political, epistemological and praxis-oriented implications of these relationships that can be uncovered by looking at the types of knowledge available in public libraries (Knudson, 2018).

This research has identified structural problems with selection practices in the Australian context that make it possible to question just how far the conventional wisdom relating to the association of public libraries with democracy and humanism (Knuth, 2003, p. 51) can be maintained. Assuming the model identified here resonates beyond the sample, could we not say that libricide (Knuth's term for acts of commission relating to destroying collections) might not also be applicable to acts of omission (allowing significant parts of adult non-fiction collections to be sequestered for entertainment rather than learning)? While entertainment should also have a prominent place, it would seem that both structurally and with reference to topicality, the picture of public library collections as pillars of democratic humanism may be, in the Australian context, unsupportable given the new evidence outlined here.

Valuable as they are, neo-liberal discourses of the library such as Knuth's fail to take into account the limited use to which we can put a sociology of knowledge that remains wedded to ideology as the appropriate level of analysis. Stark (1950, p. 288) argues that as a result of a form of historicism (or more properly historicity) relating to developments in modernity, we are forced to engage in an analysis of historical, cultural or class-based issues as objects. These objects are, at one level, alien to us and leave us questioning how we can understand others' lives when they are not close to our own milieu. Revealing our own libraries' unconscious bias, the cultural blind spots, and investigating those that cultures removed from our own maintain as well, provides a more nuanced sense of how we actually do incorporate (or inculcate) social knowledge into our daily lives and our institutional frameworks. While undoubtedly much effort to select diverse and worthy materials is undertaken, the strength of the evidence for structural failings (too many works being selected in too few categories) from this study suggests that root and branch reform is warranted to create collections that are really worth patronising.

Conclusion

A significant part of how library collections can help to define what the sociology of scientific knowledge means to civil society is through helping to draw a linkage between what non-fiction knowledge is, or is not, represented in public library collections and how we understand the sociological factors that contribute to acts of selection or non-selection. The civil society cohort at its most basic level, is not more defined than all users and potential users of a library. This cohort has been referred to previously as worthy of deeper theoretical attention (Kelly, 2014, 2018). Differentiating who is the civil society cohort in this context is rather simple: it is all readers whose reading needs cannot be met by either an academic library or through recourse to private resources. While some academic libraries will not place limits on the types of knowledge that they collect, they will, quite obviously, prioritise knowledge that has merit for scholars. The civil society knowledge mandate, at one level, cannot be restricted. Potentially, any material in demand by a public library user might reasonably be acquired.

However, we generally only rule out routinely acquiring works that are of interest to students or researchers in academic environments, or works that are of professional interest to those engaged in a particular industry or sector. Both of these types of materials and, importantly, the reading culture that accompanies them, are not subsumed within the notion of a civil society library that is presented here. It is entirely possible that small numbers of works that fit the academic or professional library might be collected but the point is that either the category or subject are not of critical interest to a given civil society cohort or, more likely, the particular topicality of an individual work is itself not of interest (i.e., the level of treatment of the topic by the work is presently beyond the ability of civil society to appreciate).

The question of how we draw the boundary of what topics or what treatments of topics are beyond the abilities of civil society to appreciate at any given time is a sociological question. While we may have answers in terms of language complexity or skills acquisition (mathematical, logical or discipline specific in nature), there are other factors that contribute. The ability to engage with extended argument; the perceived right to know certain material in terms of one's identity (class, gender, ethnicity, sexuality, political affiliation, age, disability status); the utility of materials toward goal formation in terms of personality or cognition: all of these factors contribute something to defining a boundary as reasonable or not (Bowker and Star, 1999). Based upon the results of the research presented here, at least in the Australian context, public libraries are putting too many boundary markers up in the form of limiting selection decisions to a narrow band of knowledge domains. This has potentially serious implications for the institution but more than that, potentially serious ramifications for learners seeking an accessible resource of cosmopolitan cultural and scientific materials.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank the Online Computer Library Center for their generous assistance in making the collection data available, the public libraries who provided permission to access this data and two anonymous reviewers whose helpful comments and suggestions improved the final version of this paper.

About the author

Matthew Kelly is a doctoral candidate at the University of South Australia where he is researching the epistemic factors influencing non-fiction selection in public libraries. E-mail contact: mattkelly.curtin@gmail.com

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2018a). Regional population growth, Australia, 2016-17. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/3218.0 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/78ryLfLLD)

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2018b). Migration, Australia, 2016-17. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved from http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts /3412.0Main%20Features42016-17?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=3412.0&issue=2016-17&num=&view= (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/78rz3WmEd)

- Baruchson-Arbib, S. & Bronstein, J. (2002). A view to the future of the library and information science profession: a Delphi study. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 53(5), 397-408.

- Bhardwaj, R. K. & Margam, M. (2017). Metadata framework for online legal information system in Indian environment. Library Review, 66(1/2), 49-68.

- Bowker, G. C. & Star, S. L. (1999). Sorting things out: classification and its consequences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Bradford, S. C. (1934). Sources of information on specific subjects. Engineering, 137(3550), 85-86.

- Ceynowa, K. (2009). Mass digitization for research and study: the digitization strategy of the Bavarian State Library. IFLA Journal, 35(1), 17–24.

- Das, L. H. (2002). Library partnerships in The Netherlands. School Libraries Worldwide, 8(2), 82.

- De Schepper, G. (2013). Elektronische stadspublicaties: bewaren en toegankelijk maken [Electronic city publications: preserve and providing access]. META: Tijdschrift voor Bibliotheek & Archief, 89(7), 34-35. Retrieved from https://www.vvbad.be/meta/meta-nummer-20137/elektronische-stadspublicaties-bewaren-en-toegankelijk-maken (Archived by WebCite® http://www.webcitation.org/78rzITBSI)

- Dickey, T. J. (2011). Books as expressions of global cultural diversity. Library Resources & Technical Services, 55(3), 148-162.

- Eberhart, G. (1997). The outsourcing dilemma. American Libraries, 28(5), 54-56.

- Edem, M B. (2010). Gifts in university library resource development in the information age. Collection Building, 29(2), 70–76.

- Eskett, P. (2011). Strong foundations on shaky ground: the Upper Riccarton school/public library, New Zealand. Australasian Public Libraries and Information Services, 24(4), 172–181.

- Gyeszly, S. D. & Ismail, M. (2003). American University of Sharjah library: a collection development project. Collection Building, 22(4), 167-176.

- Hawkins, D. T. (2010). Necessity is the mother of invention: the 29th Charleston conference. Information Today, 27(1), 25-26.

- Henry, E., Longstaff, R. & Van Kampen, D. (2008). Collection analysis outcomes in an academic library. Collection Building, 27(3), 113-117.

- Herzog, G. (2006). The ‘zentralarchiv des internationalen kimsthandels ZADIK'. Art Libraries Journal, 31(1), 11-16.

- Hill, L. L., Janee, G., Dolin, R., Frew, J. & Larsgaard, M. (1999). Collection metadata solutions for digital library applications. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 50(13), 1169-1181.

- Hjørland, B. (2001). Towards a theory of aboutness, subject, topicality, theme, domain, field, content – and relevance. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 52(9), 774-778.

- Hjørland B. & Nicolaisen J. (2005). Bradford's law of scattering: ambiguities in the concept of ‘subject'. In F. Crestani & I. Ruthven (Eds.), Context: nature, impact, and role: CoLIS 2005. Berlin: Springer. (Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 3507).

- Hood, W. W. & Wilson, C. S. (2001a). The scatter of documents over databases in different subject domains: how many databases are needed? Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 52(14), 1242-1254.

- Hood, W. & Wilson, C. (2001b). The literature of bibliometrics, scientometrics, and informetrics. Scientometrics, 52(2), 291-314.

- Ilik, V., Storlien, J. & Olivarez, J. (2014). Notes on operations metadata makeover: transforming MARC records using XSLT. Library Resources & Technical Services, 58(3), 187-209.

- Intner, S. S. (2002a). Ten steps to great collections. Technicalities, 22(4), 1–5.

- Intner, S. S. (2002b). Voodoo accounting in collection development. Technicalities, 22(5), 1–10.

- Jing, G. & Jin, C. (2009). The innovative university library: strategic choice, construction practices and development ideas. Library Management, 30(4), 295-308.

- Johnson, J. (2010). From real challenges to virtual reality: realising your collection through digital partnership. Computers in Libraries, 30(9), 18-22.

- Johnson, P. (2018). Fundamentals of collection development and management. Chicago, IL: ALA Editions.

- Jones, R. A. (2005). Empowerment for digitisation: lessons learned from the making of modern Michigan. Library Hi Tech, 23(2), 205-219.

- Katsányi, S. (1995). Párhuzamos életrajzok. Gulyás Pál, Szabó Ervin és a korszerű közkönyvtár gondolatának kibontakozása [Parallel biographies: Pál Gulyás, Ervin Szabó and the idea of a modern public library]. Könyvtári Figyelő, 41(2), 199-208. Retrieved from https://epa.oszk.hu/00100/00143/00014/pdf/EPA00143_konyvtari_figyelo_1995_2_199-208.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/304O7wp).

- Kelly, M. (2014). Assessing the relative value of domain knowledge for civil society's libraries: the role of core collections. In Libraries in the Digital Age (LIDA) Proceedings, Vol. 13, 8p. Retrieved from http://ozk.unizd.hr/proceedings/index.php/lida/article /viewFile/127/229 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2YRy7lb).

- Kelly, M. (2015). An evidence-based methodology to facilitate public library non-fiction collection development. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 10(4), 40-61. Retrieved from https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/eblip/index.php/EBLIP/article/ view/25414 (Archived by WebCite® http://www.webcitation.org/78rzfaUwd)

- Kelly, M. (2018). Non-fiction: an unnaturally naturalised concept for collection development. Collection and Curation, 37(2), 65–78.

- Kilarova, I. (2007). Verejne kniznice v statistickych udajoch a vysledkoch vyskumov o mieste kniznic v systeme miestnej kultury [Public libraries in statistical data and research results relating to the position of libraries in the system of local culture]. Kniznica, 8(2-3), 3-17.

- Knudson, S. (2018). Exploring engagement with non-fiction collections: sociological perspectives. Collection and Curation, 37(2), 43-49.

- Knuth, R. (2003). Libricide: the regime-sponsored destruction of books and libraries in the twentieth century. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

- Koenig, J. & Mikeal, A. (2010). Creating complex repository collections, such as journals, with Manakin. Program, 44(4), 393-402.

- Kulisiewicz, W. (2010). The Sejm Library, 1919-2009. Library Trends, 58(4), 486-501.

- Larivière, V., Sugimoto, C. R. & Cronin, B. (2012). A bibliometric chronicling of library and information science's first hundred years. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63(5), 997-1016.

- Lihua, W. & Lu, L. (2006). User profiling for personalised recommending systems—a review. Journal of the China Society for Scientific and Technical Information, 25(1), 55-62.

- Lee, H.-L. (2005). The concept of collection from the user's perspective. The Library Quarterly, 75(1), 67-85.

- Liu, D. (2017). SoLoMo concept-based service marketing in medical library. Chinese Journal of Medical Library and Information Science, 26(2), 51–54.

- Lutz, M. & Meadow, C. (2006). Evolving an in-house system to integrate the management of digital collections. Library Hi Tech, 24(2), 241–260.

- Madsen, D. W. (1999). Guide to managing approval plans. Technicalities, 19(2), 13-14.

- McGee, D. (2015). Assessing the Borrow Direct engineering e-book pilot. Interlending & Document Supply, 43(4), 174-178.

- Nash, A. (2006). ‘We're open!'. Library Journal, 131(15), 8.

- Nikolaidou, M., Anagnostopoulos, D. & Hatzopoulos, M. (2005). Development of a medical digital library managing multiple collections. The Electronic Library, 23(2), 221-236.

- Odell, J. & Gabbard, R. (2008). The interdisciplinary influence of library and information science 1996–2004: a journal-to-journal citation analysis. College & Research Libraries, 69(6), 546-565.

- Oliphant, T. & Shiri, A. (2017). The long tail of search and topical queries in public libraries. Library Review, 66(6/7), 430-441.

- Parichi, R. & Nisha, F. (2015). Greenstone digital library management system: a functional review based on selected criteria. Library Hi Tech News, 32(10), 16-21.

- Paskoff, B. M. & Perrault, A. H. (1990). A tool for comparative analysis: conducting a shelflist sample to construct a collection profile. Library Resources and Technical Services, 34(2), 199-215.

- Price, A. & Kresh, D. (2002). ‘The truth is out thereß: QuestionPoint, a global digital reference service. DF Revy, 25(5), 113-114.

- Schaffler, H. (2004). How to organise the digital library: reengineering and change management in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich. Library Hi Tech, 22(4), 340-346.

- Stark, W. (1950). Towards a theory of social knowledge. Revue Internationale de Philosophie, 4(13) 287-308.

- Stellingwerff, J. (1977). The conception of the free university library. In W.R.H. Koops and J. Stellingwerff, (Eds.), Developments in collection building in university libraries in Western Europe: papers presented at a symposium of Belgian, British, Dutch and German university librarians, Amsterdam, 31st March–2nd April 1976. (pp. 98-104). Munich, Germany: Verlag Dokumentation.

- Szasz, K. (2001). Kozkonyvtaraink s az egy orszagos konyvtar [Our public libraries and the one national library]. Konyvtari Figyelo, 47(3), 437-448.

- Trueswell, R. L. (1969). Some behavioural patterns of library users: the 80/20 rule. Wilson Library Bulletin, 43(5), 458-461.

- Wagner-Döbler, R., Borchardt, C., Müller, A., Richter, J., Albrecht, B., Knigge, U. & Kressi, U. (2003). Literaturversorgung auf fünf Sondersammelgebieten 1991-2000 [Literature supply in five special collection areas 1991-2000]. Bibliothek Forschung und Praxis, 27(3), 189-194.

- White, H. D. (1995). Brief tests of collection strength: a methodology for all types of libraries. Westport, CN: Greenwood Press.

- White, H. D. (2008). Better than brief tests: coverage power tests of collection strength. College & Research Libraries, 69(2), 155-174.

- White, H. D. & McCain, K. W. (1997). Visualisation of literatures. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 32, 99-168.

- White, H.D., Boell, S.K., Yu, H., Davis, M., Wilson, C.S. & Cole, F.T. (2009). Libcitations: a measure for comparative assessment of book publications in the humanities and social sciences. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60(6), 1083-1096.

- Wilson, T.D. (1980). On information science and the social sciences. Social Science Information Studies, 1(1), 5-12.

- Woodward, H. & Evans, A. J. (1984). Serials cuts (and the use of a blunt knife). In R. M. Burton (Ed.), SERIALS ‘83: Proceedings of the UK Serials Group Conference held at University of Durham 21-24 March 1983 (pp. 111-122). London: UK Serials Group.

- Yan Lee, K. & Freedman, J. (2010). Odd girl in: expanding lesbian fiction holdings at Barnard College. Collection Building, 29(1), 22-26.

How to cite this paper

Appendices

Appendix 1 - OCLC conspectus divisions

|

Agriculture Anthropology Art & architecture Biological sciences Business & economics Chemistry Communicable diseases & miscellaneous Computer science Education Engineering & technology Geography & earth sciences Government documents Health facilities, nursing & history Health professions & public health History & auxiliary sciences Language, linguistics & literature |

Law Library science, generalities & reference Mathematics Medicine Medicine by body system Medicine by discipline Music Performing arts Philosophy & religion Physical education & recreation Physical sciences Political science Preclinical sciences Psychology Sociology |

Appendix 2 - Relationship between top five sample aggregated categories and associated divisions and subjects

Note: The top five sampled categories are shown as bold and underlined.

Two divisions (Engineering & technology and History & auxiliary sciences) are repeated because they embrace two categories each (Domestic engineering and Handicrafts, arts and crafts for the former and History-Oceania and History-general for the latter). All the categories for the division are listed in the category column for purposes of comparison. The subject column is specific to the category (bold and underlined) and lists subjects specific to that category only.

| OCLC Division | OCLC Category | OCLC Subjects Linked to highlighted category | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engineering and technology |

General technology General engineering Hydraulic engineering Military engineering Navigation, merchant marine Naval architecture, shipbuilding, etc. Environmental technology Highway engineering Railroad engineering Bridge engineering Building construction Mechanical engineering & machinery Electrical engineering Motor vehicles, aeronautics, astronautics Mining engineering & metallurgy Chemical technology Manufactures Handicrafts, arts & crafts Domestic engineering Printing |

Domestic engineering Home economics, general House Consumer education Clothing Nutrition, food & food supply, general Consumer nutrition Nutrition policy Diet & nutrition - special groups Nutrition - animal & vegetable foods Food chemistry, analysis Dietary studies, food values Food preservation Gastronomy Cookery - cookbooks, early to 1800 Cookery - history Cookery - cookbooks, general Cookery - cookbooks by region & country Cookery - cooking with wine, etc. Cookery - menus, bills of fare, etc. Cookery - by ingredient or technique Dining room service Hotel/restaurant, food service, general Hotel/restaurant, food service - law & legislation Hotel/restaurant, food service - operations Taverns, bar rooms Mobile home & recreational vehicle living | ||

| History and auxiliary sciences |

Auxiliary sciences of history, general History of civilisation & culture Seals Archaeology, general Prehistoric archaeology Heraldry Genealogy Biography History, general History of Europe, general History: Great Britain History: Central Europe, general History: Austria, Austro-Hungarian Empire, Liechtenstein History: France, Andorra, Monaco History: Germany History: Mediterranean Region, Greco-Roman World History: Greece History: Italy History: Netherlands, Low Countries & Belgium |

History: Eastern Europe, general History: Russia, Soviet Union Eastern Europe, Northern Area Central Asian & Far Eastern Republics History: Northern Europe, Scandinavia History: Spain History: Portugal History: Switzerland History: Balkan Peninsula History: Hungary, Czechoslovakia History: Poland History: Asia, general History: S.W. Asia, Middle East History: Southern Asia, Indian Ocean History: Eastern Asia, S.E. Asia, Far East History: Africa History: Oceania, South Seas Gypsies |

History: Americas, general, Indian, North America History: United States, colonial, special topics History: United States, Revolutionary period History: United States, 1790-1861 History: United States, slavery & Civil War History: United States, since the Civil War State & local history: New England, Atlantic coast State & local history: South, Gulf states State & local history: Midwest, Old Northwest State & local history: The West State & local history: Pacific states, territories History: British/French/Dutch America, Canada History: Mexico History: Latin America, Spanish America, general History: Central America History: West Indies Caribbean area History: South America |

History - Oceania, South Seas Oceania, general Australia, general New South Wales Tasmania Victoria Queensland South Australia Western Australia Northern Territory New Zealand New Zealand - local history & description Melanesia, general Micronesia, general Western New Guinea (Irian Barat) Polynesia, general Hawaii |

| Physical education and recreation | Recreation Sports Physical training Games & amusements Hunting sports |

Sports History Biography Sports for special classes of people Athletic contests, sports events Air sports Water sports Winter sports Roller skating. Skateboarding Ball games Other sports Horse sports, horse shows, driving, horsemanship Horse racing Angling | ||

| Engineering and technology |

General technology General engineering Hydraulic engineering Military engineering Navigation, merchant marine Naval architecture, shipbuilding, etc. Environmental technology Highway engineering Railroad engineering Bridge engineering Building construction Mechanical engineering & machinery Electrical engineering Motor vehicles, aeronautics, astronautics Mining engineering & metallurgy Chemical technology Manufactures Handicrafts, arts & crafts Domestic engineering Printing |

Handicrafts, arts & crafts Arts & crafts, general Manual training, school shop Articles for children Woodworking, furniture making, upholstery Metalworking Painting, finishing Soft home furnishings Clothing manufacture, dressmaking, merchandising Home sewing, embroidery, decorative crafts Hairdressing Laundry work | ||

| History and auxiliary sciences | Auxiliary sciences of history, general History of civilisation & culture Seals Archaeology, general Prehistoric archaeology Heraldry Genealogy Biography History, general History of Europe, general History: Great Britain History: Central Europe, general History: Austria, Austro-Hungarian Empire, Liechtenstein History: France, Andorra, Monaco History: Germany History: Mediterranean Region, Greco-Roman World History: Greece History: Italy History: Netherlands, Low Countries & Belgium |

History: Eastern Europe, general History: Russia, Soviet Union Eastern Europe, Northern Area Central Asian & Far Eastern Republics History: Northern Europe, Scandinavia History: Spain History: Portugal History: Switzerland History: Balkan Peninsula History: Hungary, Czechoslovakia History: Poland History: Asia, general History: S.W. Asia, Middle East History: Southern Asia, Indian Ocean History: Eastern Asia, S.E. Asia, Far East History: Africa History: Oceania, South Seas Gypsies |

History: Americas, general, Indian, North America History: United States, colonial, special topics History: United States, Revolutionary period History: United States, 1790-1861 History: United States, slavery & Civil War History: United States, since the Civil War State & local history: New England, Atlantic coast State & local history: South, Gulf states State & local history: Midwest, Old Northwest State & local history: The West State & local history: Pacific states, territories History: British/French/Dutch America, Canada History: Mexico History: Latin America, Spanish America, general History: Central America History: West Indies. Caribbean area History: South America |

History, general History - periodicals, congresses, dictionaries Historiography/pethodology/philosophy/study & teach World hist. & chronicles to 1800, inc. ancient history General works, 1801-, textbooks, general popular Historical events, including disasters Military & naval history, inc. Europe Political & diplomatic history inc. Europe History, ancient, inc. Europe History, medieval, inc. Europe History, modern, 1453-, general works 1453-1648, 16th cent., Reformation, Counter-Reformation 1601-1715, 17th century 1715-1789, Enlightenment, ancient regime 1789-1815, French Revolution & Napoleonic period 19th century to 1871 1871-1914. 20th century World War I Period between the World Wars, 1919-1939 World War II Pacific Ocean theatre Post-War history 1945- 21st century |