Research data sharing during the Zika virus public health emergency

Vanessa de Arruda Jorge and Sarita Albagli.

Introduction. In a public health emergency, sharing of research data is acknowledged as essential to manage treatment and control of the disease. The objective of this study was to examine how researchers reacted during the Zika virus emergency in Brazil.

Method. A literature review examined both unpublished reports and the published literature. Interviews were conducted with eleven researchers (from a sample of sixteen) in the Renezika network. Questions concerned sources of data used for research on the Zika virus, where this data was obtained, and what requirements by funding agencies influenced how data generated was shared – and how open the degree of sharing was.

Analysis. A content analysis matrix was developed based on the results of the interviews. The data were organised according to categories, subcategories, records units and frequency of records units.

Results. Researchers stressed the importance of access to issue samples as well as pure research data. Collaboration – and publication – increased but also depended on trust in existing networks. Researchers were aware that many agencies and publishers required the deposit of research data in repositories – and several options existed for Zika research.

Conclusions. The findings show that research data were shared, but not necessarily as open data. Trust was necessary between researchers, and researchers in developing countries needed to be assured about their rights and ownership of data, and publications using that data.

Introduction

Between 2015 and 2016, with the outbreak of the Zika virus, this epidemic stopped being a problem of a single country. Scientists worldwide searched, particularly in Brazil, for data and information about a disease that presented devastating consequences to a generation of children that were affected by the virus while still inside their mothers' wombs, risking being born with microcephaly and later developing any other pathology caused by the virus. With scarce precedents registered in the scientific literature (Diniz, 2016; Martins, 2016), researchers, health professionals and managers were faced with a new situation which demanded the fast generation of knowledge. The sharing and opening of data proved to be fundamental in this context.

Open research data is part of the movement for open science, launched since the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities (2003). The opening of data affects sensitive issues such as the priority of scientific discoveries, researcher prestige and reward. These issues are even more strategic in the health sector, given its social relevance and profit potential.

This study aimed to identify, and analyse the key factors affecting sharing of research data in the Zika public health emergency. A literature review (including examination of grey literature) was complemented by interviews with Zika researchers.

Literature review

Opening and sharing research data

Research data is understood as actual 'records (numerical scores, textual records, images and sounds) used as primary sources for scientific research, and that are commonly accepted in the scientific community as necessary to validate research findings'(Organisation For Economic Co-Operation And Development, 2007, p. 13).

Thus, they can be considered inputs and products of the research process. They are created or collected during research from other processes or activities (such as government data). The opening and sharing of research data facilitate the collaboration between researchers and teams, promoting their use in new research, the reproducibility of experiments and the verification of the quality of scientific results by peers. From this point of view, one perceives 'new patterns of socialization and of cooperative work regardless of geographical and discipline barriers' (Sayão and Sales, 2014, p. 80).

However, it is important to stress that, in practice, there is a fundamental difference between opening and sharing research data. Not every item of shared data is an open item. Data sharing can be restricted to specific organisations, groups or individuals. It can take place through informal arrangements or be regulated by access agreements that define 'the processing framework set up by research institutions, agencies and other partners involved in order to determine the conditions for the use of research data' (Organisation For Economic Co-Operation And Development, 2007, p. 14). Open data can be defined as 'data that can be freely used, re-used and redistributed by anyone - subject only, at most, to the requirement to attribute and share-alike' (Open Knowledge Foundation, n.d.). Data sharing does not always abide by these principles of open data.

In the field of science, the adoption of FAIR principles (findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable) become established and spread out as a necessary agenda to promote and to enable the conditions for the re-use of data (Wilkinson et al., 2016). The FAIR principles arise from the complexity and diversity of data created and accumulated through scientific activity. Their focus on the re-utilisation of research data with machine support establishes parameters for thinking about a global structure regarding the description of data and metadata for sharing and opening research data. In this respect, it is recommended that their use be complemented by strategies for data management, particularly data management plans, and that researchers as the main producers and users of data, become familiar with and adopt them.

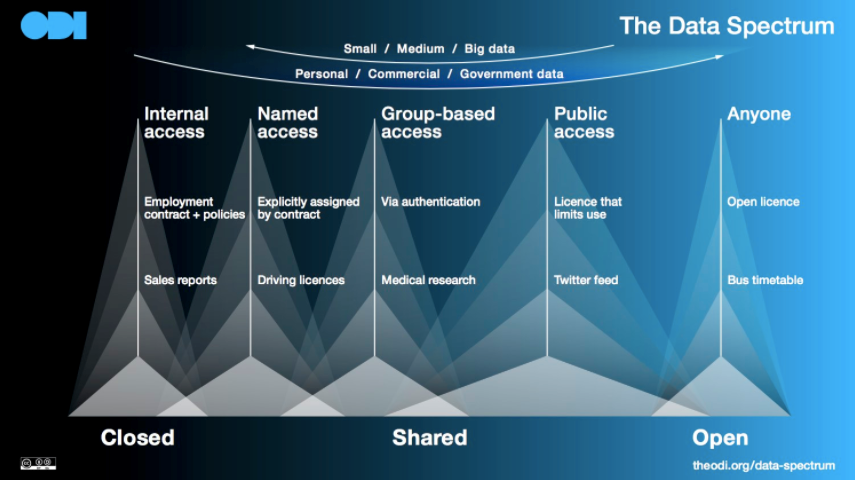

Reflecting on this issue, it is considered that openness would be the top level in a scale of access, availability, disclosure and possibility of re-use of data, as in the data spectrum proposed by the Open Data Institute (Figure 1)

According to Broad, closed data are those 'that can only be accessed by its subject, owner or holder'; shared data can be named access: 'data that is shared only with named people or organisations'; attribute-based access is 'data that available to specific groups who meet certain criteria'; and public access 'data that is available to anyone under terms and conditions that are not "open"'. Finally, the author explains that open data is 'data that anyone can access, use, and share' (Broad, as cited in Green et al., 2017, p. 63).

In situations of public health emergency, requirements for fast access to health data is necessary but collecting data and information from different systems for exchange and sharing is often impossible given the lack of interoperability of data.

The case of the Zika virus

Epidemic control and rapid response to international public health emergencies depend on a coordinated governance system. The international public health surveillance system is structured in an institutional framework under the auspices of the World Health Organization which includes the Global Alert and Response, the Early Warning, Alert and Response System, the Global Public Health Intelligence Network, and the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network.

In this context, in 2014, during the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, difficulties in the collection and sharing of data were reported, even though the disease was considered a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. As pointed out by the World Health Organization (2015), the need for global rules and norms for the sharing and opening of scientific data in such situations became evident. Genomic and epidemiological data as well as those generated through clinical studies and essays were crucial, as well as the publication in preprints, increasing the speed of circulation of information resulting from research.

In Brazil, the year 2015 was marked by the circulation and isolation of the Zika virus transmitted by the Aedes aegypti mosquito, which initially seemed benign, but which left dramatic consequences particularly in the Northeast of Brazil.

Even though it was first isolated in 1947 in Uganda, the ZIKV, or Zika virus, had launched epidemics in Yap, in Micronesia in 2007, in French Polynesia in 2013-2014 and in New Caledonia, in 2014 (Campos et al., 2015). In the first scientific paper published about the Zika in Brazil, in May 2015, the isolation of the virus in the state of Rio Grande do Norte was announced, where seven of the eight confirmed cases of the disease were female (Zanluca et al., 2015). After these cases, others were confirmed and later associated with neurological syndromes such as the Guillain-Barré syndrome, 'generally provoked by a previous infectious process and manifest muscular weakness, with reduction or absence of reflexes' (Brazil. Ministério da Saúde, n.d.) as well as congenital anomalies, such as microcephaly, in babies whose mothers contracted the virus during pregnancy.

The identification and association of the Zika virus and microcephaly put in place a series of political and social initiatives to treat and support what came to be called congenital Zika syndrome. This term, congenital Zika syndrome, came to be used to account for all the problems involving the babies who, besides microcephaly, could present, besides a head with an irregular perimeter, many other serious consequences to their organisms. By the end of 2015, the Zika virus was considered a Public Health Emergency of National Concern (Brasil, 2015) by the Brazilian government. In the beginning of 2016, a Public Health Emergency of International Concern was declared by the World Health Organization as defined by the International Health Regulations of 2005, given that there were notifications of Zika virus epidemics in twenty-four countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, besides cases reported in the US and in Europe. The progressive increase was registered in the number of cases of microcephaly and other disturbances of the central nervous system in neonates and adults associated with contamination by the Zika (Gadelha et al., 2017).

In Brazil, the scientific agenda of the Zika originated with specialists working in direct contact with patients, in doctors' offices and hospitals, with those seeking medical help. These specialists took their questions, together with pre-defined hypotheses, to laboratories and to the academic world; these helped researchers in the trial and error game which is a natural part of the process of producing scientific knowledge, in the search of answers to the emergency situation existing at that moment.

The exchange of information and data through applications such as WhatsApp was, at first, intensely used during the epidemics, reflecting the surprise of doctors in dealing with an uncommon number of cases of microcephaly. Of note, albeit not as an organised practice of citizen science, was the participation of mothers, who offered to scientific research their own bodies and those of their children, dead or alive.

Brazilian science played a major role during the period of the Zika epidemics. At that time, the Zika was considered a new virus circulating around Brazilian territory. There were no records either in the national or the international literature about this association and soon it came to be considered unprecedented in the field of science.

Studies on the scientific contribution of Latin American and Caribbean countries to the struggle against the Zika virus epidemics (Machado-Silva et al., 2019) show that, in the period from 2007 to 2017, Brazil was the second country in the world in terms of number of publications on the topic and the third most central in the global network of research on the Zika, below the USA and France (in the study carried out by Machado-Silva et al., the network analysis was based on co-authorship of articles). The study shows that the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fundação Oswaldo Cruz - Fiocruz), a public organisation for research in health, was the institution with the largest volume of scientific publications with the widest international reach on this topic. This fact can be attributed to the investment, at the time, in science and technology in the country, which was crucial to the Brazilian performance in response to the epidemics.

International financing, particularly from Europe and the US came only after the confirmation of the scientific evidence of the causal relation between the virus and microcephaly. International research consortia (such as ZikAction, ZikAllince and Zika Plan) were also set up, contemplating initiatives connected to the sharing of data.

The appeal for the sharing of research data was present throughout the Zika epidemics and continued after the period of the greatest emergency. Once the disease was declared to be a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, the majority of scientific research on the Zika started being financed or developed by institutions possessing established guidelines and policies for data sharing such as the National Institutes of Health, the European Commission (with the Horizon 2020 Programme), the Medical Research Council, the Welcome Trust, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research as well as others (Jorge, 2018).

Throughout the period when international emergency was declared, several international institutions, including research funding agencies, journals and research institutions, signed the Statement on Data Sharing in Public Health Emergencies (Wellcome Trust, 2016). The declaration also stressed the importance of open access to scientific publications, a movement preceding the open data movement, but which required reminding and reiteration during the Zika epidemics. Beyond data and scientific information, there was also great demand for human material samples for analysis and for the creation of laboratory data, upon which different scientific research projects depended for viability.

Based on previous experience, the World Health Organization had already been working on Developing Global Norms for Sharing Data and Results during Public Health Emergencies (World Health Organization, 2015). In the case of the Zika, it proposed a new protocol for the submission of research data on the virus - the Zika Open (Dye et al., 2016). The Zika Open established a special workflow, according to which relevant papers on the Zika virus would receive a digital object identifier (DOI) and would be placed online within twenty-four hours while going through the peer-review process, being placed under the license Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Intergovernamental (CC BY IGO 3.0). If, after the peer-review process, the paper was accepted by the journal, the period during which it remained in open access while being reviewed would be reported in the final publication. This model, known as fast track, was adopted by various scientific journals, including Brazilian ones, such as Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz (Pirmez et al., 2016).

In fast track, the difference in relation to the traditional publication process is the speeding up of the review of papers and other processes, shortening the time of publication. A study developed by Albuquerque et al. (2017) established that prestigious scientific journals demanded articles on the Zika virus during the period of international emergency, offering a quick analysis of submissions, through a simplified peer review process, with immediate publication following the paper's acceptance. Among the publishers adopting fast track were the American Association for the Advancement of Science; Elsevier; New England Journal of Medicine group; Oswaldo Cruz Foundation; Oxford University; and the Public Library of Science (PLOS). Throughout this period, growth in the number of papers published in open access journals with results of research on the Zika virus was also observed (Araujo et al., 2017, p. 7).

To Henriques, the sharing of information, beyond the integrated and collaborative work, was essential to the answer provided by science. According to the author

I am unaware of any other moment in our history in which so many brains, in record time, have agreed to cooperate towards a common objective. Everyone working in an open manner, generously disclosing their data without waiting for publication, sharing samples, materials, structures and ideas. There were those who celebrated Christmas in their lab and brought as a present a successful viral culture. (Henriques, 2017, p. 24).

In 2018, based on the lessons learned during the Zika international emergency period, the Global Research Collaboration for Infectious Disease Preparedness (GloPID-R) published a set of guidelines in order to establish a global system of data sharing for these cases. Through its work group on data sharing, the GloPID-R listed seven fundamental principles to be followed in such situations. These are: (a) timing (data shared and made available in the shortest possible time); (b) ethics (data sharing that respects applicable ethical and legal standards, confidentiality, the privacy of individuals and the dignity of communities); (c) accessibility (data with the least possible restrictions, both technical and legal, indicating the existence of conditions, if any, and for how long they apply); (d) transparency (the process of sharing data and the facilitation of access must be clearly explained); (e) equity (data must be made available to all interested parties without cost or just at a level of recovering costs without profit, with equal access to data); (f) justice (the provision and use of data must be fair to all parties involved, acknowledging the contribution of the provider and/or the origin of the data, and must reflect international agreements for the sharing of benefits); (g) and quality (a minimum standard of quality of the data must be ensured by the provider, while users of data must also ensure that the processing, analysis and interpretation of the data must be carried out with equivalent or higher quality standards) (Global Research Collaboration for Infectious Disease Preparedness, 2018).

Methods

The methodology involved bibliographic and documental research, a literature review, and interviews, in which content analysis was performed. The motivation underlying the interviews with professionals engaged in research about the Zika virus in Brazil was to understand if and how, in practice, sharing of data and open science took place, as well as the perception of interviewees about this process. The interviews sought to listen to professionals who developed work on the topic, participating in research projects related to the Zika virus, including those who did it through their professional practice such as doctors and technical staff from the Ministry of Health during the period of public health emergency.

In the selection of interviewees, we considered participants of the Renezika, a network structured by the Brazilian Ministry of Health encompassing primarily Brazilian researchers, some of whom worked in foreign institutions. Besides researchers, the selection also included professionals whose main activity was not research, but who co-authored the publication of scientific papers because they had new and important data included in the published research results.

The database consulted was Pubmed (a search engine of MEDLINE, an important bibliographical database in the health discipline), using the following search strategy: search expressions were the word Zika, with the names of Renezika members (a total of 133 members in May 2017), with a filter for the publication period defined as January 1, 2015 to May 31 2017. This period encompasses, at the initial date, the earliest reports of the circulation of the virus in Brazil and, at the final date, the month when the government announced the end of the public health emergency of national importance in the country. The purpose of this search was to identify the number of scientific publications by each member of the group and to select those who had at least four papers indexed in the database. We selected for the interviews those researchers who were able to publish more quickly results of their research, on the basis of the hypothesis that the collaboration, the sharing and opening of data favoured the required speed in response to the emergency situation.

Based on the results obtained according to the adopted criteria, a total of sixteen researchers were selected for the interview, of which we were able to interview eleven (four face-to-face, six via Internet with the software Skype and one by telephone). The interviewees have backgrounds in different subject areas and different areas of activity, both professional (infectious and tropical diseases; cellular immunology; diagnostic testing; epidemiology; neurology; bioethics; virology; public health and the environment; pathogeny), and institutional (all of them belonging to public institutions, mainly of research and teaching).

The interviews were conducted between September 2017 and February 2018, using a script of semi-structured questions. All interviews were given in Portuguese and translated into English for the purposes of this paper. A pre-test of the interview script was made. An analytical matrix of results was carried out, tested and completed for each interviewee, with reference to Bardin's (2011) theory of content analysis, considering the criteria of completeness, representativeness, homogeneity, relevance, and exclusivity. We tested the structure created for content analysis and pre-tested the questionnaire. The records were then grouped and refined, generating matrices by category and subcategory. Table 1 below shows the questions asked to interviewees, relating them to the categories and subcategories created for the analysis.

| Questions | Category defined for content analysis | Subcategory defined for content analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Which were the initial main sources of data employed by your research on the Zika? | Access to research data | Sources of research data |

| How did you have access to these data? What conditions were established for this access? | Conditions of access to research data | |

| Did you share your research data? If yes, where and how, under what conditions? | Sharing of produced data | Ways of opening and/or sharing resulting data |

| Did any funding agency, scientific journal or any other actor request the sharing and/or opening of the data generated by your research as a condition to any kind of relationship (research financing, publication of paper etc.)? | Sharing as a condition to the relationship of actors in the field of science | |

| Do you know portals, databases and/or repository that contain scientific research data on the Zika? Are these open access infrastructures? | Known data initiatives | Portals, repositories, databases |

| Did the declaration of public health emergency influence and/or help in the opening and sharing of scientific research data developed in this period on the Zika, as well as in the dissemination and publication of research data? How? | Perception of the declaration of public health emergency | Change in traditional practices of sharing, dissemination and publication |

| Did the end of the emergency reverberate on the circulation of information and knowledge of this topic? | Experiences that impacted the research process | |

| Based on this and other experiences, which factors contributed to the sharing and opening of research data? | Perception of the sharing or opening of data | Contributing factors |

| And which factors hindered the sharing and opening of research data? | Hindering factors |

Findings

The following table presents a systematisation of the interview results, organised according to the content analysis categories, the terms corresponding to the record units and the number of occurrences in the answers.

| Category | Subcategory | Records units | Frequency of records units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access to research data | Sources of research data | Scientific literature | 10 |

| Ministry of Health databases | 4 | ||

| Research materials (samples) | 8 | ||

| Clinical and laboratory data | 5 | ||

| Data collection during the Zika outbreak | 5 | ||

| Contact with other researchers | 3 | ||

| Conditions of access to research data | There were none | 3 | |

| Collaboration agreements | 8 | ||

| Official authorisations (Ethics committees and hospitals) | 2 | ||

| Existing networks | 1 | ||

| Data sharing | Ways of opening and/or sharing the data produced | Collaboration with foreign groups | 4 |

| Barriers to research materials and data sharing | 6 | ||

| Projects/Research protocol | 3 | ||

| Publication of the Ministry of Health's data | 4 | ||

| Collaboration between research groups | 4 | ||

| Research material sharing | 2 | ||

| Articles and preprints | 4 | ||

| Research networks (Renezika, Rede Zika etc) | 3 | ||

| Government Institutions | 3 | ||

| Data sharing as a condition for relationships with other scientific actors | Data sharing was not a condition for relationships with other scientific actors | 7 | |

| Scientific journals | 4 | ||

| Funding agencies | 2 | ||

| Perception of Public Health Emergency | Perception of Public Health Emergency declaration (national and international) | Fast track | 8 |

| Open access to scientific publications | 4 | ||

| Preprint | 2 | ||

| Statement on data sharing in public health emergencies | 2 | ||

| Experiences that impacted the research process | Research funding | 5 | |

| Agility in processes and procedures (publication process, ethical approvals, others) | 4 | ||

| Circulation of information | 2 | ||

| Run for publication | 2 | ||

| Research time | 2 | ||

| Affected parties | 2 | ||

| Focus on Zika research | 1 | ||

| Mobilisation of public opinion | 1 | ||

| Perceptions of favourable and unfavourable factors in data sharing | Contributing factors | Advance of science | 6 |

| Open access to data and information | 4 | ||

| Equal access to public data | 1 | ||

| More robust publications | 1 | ||

| Reproducibility | 2 | ||

| Data sharing is not positive | 1 | ||

| Hindering factors | Current scientific communication model | 4 | |

| Authorship | 4 | ||

| Unequal conditions | 3 | ||

| Fear of mistake | 3 | ||

| Discovery Priority | 4 | ||

| Academic Productivity | 3 | ||

| Sensitive data protection mechanisms | 1 | ||

| Data sharing motivated by research interest | 1 |

Discussion

The most important results of the content analysis of the interviews according to the adopted categories are organised under the thematic axes presented below.

Access to research data

Scientific literature was mentioned by almost all interviewees as the first source for their research on the Zika virus. Nevertheless, interviewees indicated that there were few scientific articles on the topic at the beginning of the emergency. According to a bibliometric study, the number of publications on the Zika 'varied from two publications, in 1952, to 70 in January 2016' (Martins, 2016, p. 8), increasing particularly in French Polynesia from 2012 and from 2015 worldwide. Thus, it was necessary to search for data from other countries, such as the epidemics of the disease in French Polynesia, where it was believed that evidence of the association of the Zika virus with microcephaly could be found.

Research material (the isolated virus, human tissue, substances collected during examinations), clinical data and governmental databases with notifications of the disease were the main input for research projects on the Zika during the emergency period. However, problems of under-reporting of the disease in official records were identified, restricting the use of these sources for research.

Conditions of access to data and materials were governed by agreements, protocols and collaboration actions so that research projects could be carried out at maximum speed. 'The Secretariat of Health had a technical team, who, realising the urgency and considering an external demand for research projects, asked to make a collaboration protocol' (Interview 2, 2017). This access also took place in an informal manner, through contact with other researchers, in different meetings with the presence of several specialists in order to share information on the disease. 'We [research group] connect very well and universities connect very well and there was no problem with that [sharing research material]' (Interview 10, 2017).

It was also stressed that most data still did not exist, they were being produced and collected during the new epidemics, either by research groups or by primary health care. Clinical data on the effects of the Zika on the organism were being generated mainly in health services, such as hospitals, first aid posts and clinics, in sum, places where patients sought help for their illness. There was a lot of negotiation among doctors, who were the target of the patients' trust and hope, researchers and their research groups, supervision structures, universities, other institutions that had reference laboratories or were recognised for their expertise, or a combination of these instances.

These results lead to a reflection on the very concept of research data. When questioned about their source of data, eight researchers referred to what is commonly called research material (biological samples, the isolated virus, cell cultures, collected from individuals contaminated by the disease), equal to the number of responses that pointed out the scientific literature as their main source. Data was considered something that might not be recorded on media (computer, paper or other), but which provides input to different lab analyses. Similarly, a broader conceptualisation of the term document can be found in Buckland (1997) and Briet (1951).

As pointed out by Lowrance (2012), some research activity can only exist with simultaneous access to data and materials, that is, data and materials are linked and accessing them includes seeing, duplicating, manipulating, analysing, translating, cryptography, attaching, forwarding, storing, filing or destroying. In the case of the Zika, laboratory analysis of these materials could provide significant responses to the disease at that moment, generating a lot of laboratory data based on their processing.

Data sharing

Data and materials circulating about the Zika were not in the public domain and, for this reason, they were negotiated by different means during the emergency period between those who had the data and those who would like to receive them. Collaboration was the practice referred to most often by interviewees as being associated with a kind of partial data sharing, for the most part governed by agreements, protocols and other types of collaboration initiatives with specific groups, most of them foreign. In some cases, collaboration had at its foundation relationships of trust previously established (personal and/or professional), whether through working together or through shared periods of academic studies that fostered the sharing of tacit knowledge. Situations of data sharing with research funders were also pointed out. It was then observed that, despite the fact that the difference between the concepts of data sharing and open data is not known among researchers, sharing is more frequently practiced than opening data.

It was also made evident that, at the moment of emergency, Brazilian research groups had a relative advantage in relation to foreign ones. Brazilians had the clinical cases, the samples and other research materials that were the basis for the generation of research data on diseases associated with the Zika virus, a fact that gave rise to great interest on the part of foreign groups to set up collaborative projects. On the other hand, foreign researchers counted on financial resources, methods, cutting-edge technology and infrastructure for the analysis of accessed data and materials, often offered as counterpart.

Collaboration resulted mainly in the publication of scientific articles. However, some of the interviewees stressed that, in this respect, the public health emergency did not bring about any changes to these practices. Each author or team contributed with the data analysed by them, the sharing of all data among all members not necessarily being part of the collaboration.

Nevertheless, part of the international collaboration took place after the Brazilian laboratory already had published robust results. In these cases, interviewees explained that, even though they had been approached by foreign research groups during the early stages of the research, they chose to collaborate only after they had disclosed some results through formal vehicles of scientific communication (mainly through the publication of papers in scientific journals in the area) demonstrating the propriety and originality of their data and claiming priority of discovery.

On the other hand, interviewees also emphasised the efforts of professionals and researchers who pioneered the findings on the virus and its complications to disclose their findings as quickly as possible, in order to contribute to correlated research as well as to subsidise governmental actions with the necessary agility and urgency.

At the same time, interviewees reported the existence of barriers to the opening and sharing of data and materials related to the Zika, whether for the lack of incentives and of a structure adequate to this purpose, leaving the initiative in the hands of leaders of laboratories and research projects. 'The data was not under my management. The management was done by the head of the lab. But I think most data was not sent to any repository[…]' (Interview 1, 2017).

In addition, respondent eight explained about the control exerted by Brazilian laws on the access of these materials by industry and by academia itself.

There were even legal difficulties in transporting [biological materials]. I think a new law on the exchange of biological materials was approved, but until then there was no legislation on that. Our own legislation did not help ship the material outside of Brazil (Interview 8, 2017).

However, this particular point divided opinions. On the one hand, it was alleged that these facts had repercussions on the delay in Brazil of the development of tests and analyses relevant to the research on the virus. On the other, the point of view was expressed that, in some way, these barriers promoted the advantage of Brazilian research at the beginning of the epidemics. Given these restrictions, it was possible for Brazilian science to display its capacity and potential to develop major scientific potencies.

Perception of public health emergency

During the interviews, it was said that the most prestigious scientific journals already include in their editorial policies the request to the author to deposit his or her data in a repository; this policy was not changed during the Zika emergency. The following statement expresses the opinion of some of the respondents.

It has been the usual practice of scientific journals to request research data. I myself have submitted the data of my article as supplementary material. They usually ask for a table, with the definitions of each case and a set of related information (Interview 7, 2017).

More precisely, this study identified that six of the ten journals with the greatest impact factor in the 2016 statistics of the Journal Citation Reports present this request to authors. Besides, data normally requested by scientific journals are those that originate the articles and not those making up the totality of the research project. Thus, this request did not change the practices experienced by researchers in the health area, where these norms were already in place.

It was also noted that data sharing was already a condition of contracts signed with the main international research funding agencies. Specific mention was made of the National Institutes of Health, which has established several policies for data sharing. In this case, during the Zika virus Public Health Emergency of International Concern, data sharing was done directly and exclusively with the National Institutes of Health, through research data management systems.

In Brazil, the Foundation for the Support of Research of the State of São Paulo (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo - FAPESP) recently requested the adoption of a data management plan for funding research projects. However, during the Zika emergency, the Brazilian government, who was the main research funder in the area, did not request the sharing of data as a condition to its patronage.

Therefore, it is thought that the main alteration in traditional scientific practices of sharing, disclosing and publishing information resulting from the Zika public health emergency was the fast track, adopted during this period for the process of evaluation and publication of results.

Another issue frequently mentioned was the importance of open access to scientific publications (particularly papers in scientific journals). According to research carried out to identify references to indexed publications on the Scopus database containing the word Zika in the title, abstract or key word fields, there was an increase in the percentage of open access publications on the topic in the year 2016 – the year of the WHO appeal for open access, compared to the previous year. The number of open access publications went from 22.5% of the total results recovered through the search in the year 2015, to 33% of the total in the year 2016 (Araujo. et al., 2017). It should be emphasised, that some subscription journals that offered free access during the emergency period went back to charging for access at the end of the emergency, affecting the continuity of the research on the Zika by researchers relying on smaller research grants.

The relevance of publication of research results about the virus in preprint repositories was also emphasised. A recent study about the use of preprints in the outbreak of diseases, by Johansson et al., showed their growth as a means of disclosing new data during the outbreak of the Zika. The study uncovered a total of 174 preprint texts with the word Zika in the title or in the summary in five of the main public repositories from November 2015 to August 2017: bioRxiv - 124; arXiv - 31; F1000Research - 12; PeerJ Preprints - 5; and Zika Open - 2 (Johansson et al., 2018).

On the other hand, it was also emphasised that the preprint was not considered in several formally established international collaborations whose focus is the publication of articles in prestige journals. Another obstacle to the publication of preprints is the fact that research funding agencies do not value this type of publication when evaluating institutions or researchers, a crucial factor contributing to the incentive of the use of these publishing platforms when communicating research results.

Perceptions of favourable and unfavourable factors in data sharing

The major gain in the sharing of research data mentioned by interviewees is the advancement of research and of science itself. Bear in mind that, in the case of the Zika, a lot of new data is still necessary in order to develop a vaccine and to produce medicine, particularly for pregnant women and to protect babies. The sharing of research data is considered essential to accelerate new discoveries, more robust publications and reproducibility.

I think it is very important to share this kind of data. We must share it because a lot of data is needed to produce drugs against the Zika virus and a vaccine for its prevention. A major concern is to produce a vaccine that is safe for pregnant women and that protects babies. Sharing research data is essential (Interview 9, 2017).

Among difficulties, the current dominant model of scientific communication was considered one of the main barriers to the sharing and opening of data, as well as to the access to scientific knowledge in general, placing it under the scrutiny and criteria of major scientific editors. Still on this topic, it was pointed out that the predominance of research groups from countries with higher international profiles publishing in high-impact, prestigious journals makes it difficult for Brazilian research to acquire presence and visibility in these journals, except through joint publications with these groups. Thus, the issue of access to scientific journals remains a key aspect, not only due to the high cost of the access to published papers, but also due to the difficulty of publishing in journals maintained by the large conglomerates of commercial publishers.

I think this is an area that needs to be much debated. I am totally in favour of sharing data and information. I think these platforms came to bring a lot of good things. I think publishing agility is an important thing. It is a different system... I want to say that it's no use publishing in a prestigious journal if your work is never cited and never reproduced. This is a subject that undoubtedly needs to be debated regarding preprints and indexed magazines (Interview 3, 2017).

Competition in the priority of discovery, an aspect recurrently pointed out as an obstacle to the opening and sharing of research data in general, was also acknowledged as a significant barrier to collaboration in the struggle against the Zika virus, even despite the declaration of a national and international public health emergency.

Associated with that, another barrier mentioned to the sharing of data was the absence of credits due to authorship, indicating the distrust of researchers to the use of data reproduced and shared many times with no acknowledgement of authorship. Added to this, one can find the fear of poor interpretation of data, whose process of production and, subsequently, of analysis varies according to the subject area. It was argued that the sharing of research data in databases with due credit to authorship would enable increased security and wider adherence of researchers to data sharing. It would also help with new discoveries.

At the same time, during the outbreak of the disease in the country, the existence of an uncommon phenomenon in science was pointed out: the communication of research in the media even before any other formal communication between scientists. Many research projects first became news in the press, aimed at the health institutions themselves and, were only later published in scientific journals. As analysed by Diniz (2016), science coming from the Brazilian Northeast had to show its strength before the major centres of health research, with greater concentration in the South and Southeast of the country, and took the reins of Brazilian research. According to the author,

it is correct to say that not only a spirit of solidarity with the common good inspired medical doctors and scientists to make a move towards the press before scientific communication: it was also the unequal regime of acknowledgement of science in Brazilian society (Diniz, 2016, p. 139).

The study showed that the sharing of data took place mainly in the relationship between research groups through collaboration agreements. However, the literature shows that the word sharing is limited in comparison with opening because it restricts access to data for individuals or institutions in specific conditions. Or else, when access is open, it has its use limited by restrictive licensing or file formats that do not favour re-use.

In the case under study, acknowledgement of this distinction by researchers and professionals was not evident, but it could be observed that in practice the predominant meaning was that of the sharing or opening of data in restricted conditions. At that moment, no one considered that data sharing outside the existing model was an important option. Research results showed that the increase in the speed of scientific communication, in the shape of fast tracking and of the broadening of open access to scientific journals in the area was a more important strategy to disclose research results than data sharing by other means.

This way, the idea of sharing data for transparency, reproducibility and re-use by others in new research projects seems not to have worked during the emergency, with the exception of other health areas in which the sharing of data or a certain degree of opening is already standard behaviour such as in genomics, proteins and other closely related topics. Therefore, despite the major appeal for the sharing of data during the Zika virus emergency, including some initiatives that took place in this direction (mentioned in this paper), structural changes in scientific communication and its procedures were not observed in this situation, but only minor alterations during the emergency.

The need for new policies and conditions that might encourage a new culture and new practices aimed at opening research data in its broadest sense was pointed out. In particular, the importance of reformulating policies and metrics for evaluating research and researchers was emphasised, as well as publishing ways and policies, further strengthening the open access movement as originally formulated.

Some initiatives of data sharing on the Zika virus

When the Zika Public Health Emergency of International Concern was declared, different research projects, agreements and consortia were set up to foster collaboration among institutions and researchers, aimed at gathering efforts towards results. Within this context, the exchange of research data, information and materials were essential for obtaining complex and more thorough scientific responses. The need for studies, patterns and places for sharing data arose with the same urgency as the epidemics.

The initiatives presented below were reported during the interviews; the data were complemented with documental research in the Websites of research institutions. Results were systematised in Table 3 which presents, in alphabetical order, the name of the initiative, a short description and its Website.

| Name of the initiative | Description | Website |

|---|---|---|

| BEI Resources/Zika | Created by the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases (Instituto Nacional de Alergia e Doenças Infecciosas - NIAID), it is administered under contract by the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). It provides reagents, tools and information for studies; it also supports the deposit of materials by researchers and institutions. Access and use of these materials by the scientific community are monitored, facilitating quality control of reagents. | https://www.beiresources.org/Organism/ 118/Zika-virus.aspx |

| GitHub/Zika | A platform that supports those who are interested in learning, sharing and working together to create software. Researchers interviewed mentioned the platform as a means of support in the sharing of data on the Zika. | https://github.com/search?utf8=%E2%9C%93 &q=Zika&type= |

| Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX)/Zika | An open platform for data sharing, launched in July 2014 by the United Nations (UN), managed by the Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). It possesses a set of data on studies about the Zika virus. | https://data.humdata.org/search?q=Zika& ext_page_size=100&sort=score+desc%2C +metadata_modified+desc |

| Zika Infection/ International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC) | Maintained by the Centre for Coordination of the ISARIC. It offers a number of research tools on the Zika that, together with information for clinical doctors, researchers and other interested parties in the countries affected by the Zika, are available on the site of The Global Health Network. | https://Zikainfection.tghn.org/ |

| Knoema/Zika | A platform of open, public and free data. It works as a data search engine, connecting different sources of data, both public and private, and make data detectable and accessible to those who are interested in them. The search with the word Zika shows different results that involve data from temporal series, of visualisation and datasets | http://pt.knoema.com/ search? query=Zika |

| VectorBase/Zika virus | Focusing on vectors of invertebrates, it is one of the four Centres for Resources on Bioinformatics (Centros de Recursos de Bioinformática) financed by NIAID to provide data for basic and applied research on organisms considered as potential agents in biowarfare or bioterrorism or else, causing emerging or re-emerging diseases. It shares data on the aedes mosquito, a vector for the Zika virus. | https://www.vectorbase.org/ organisms/ Zika-virus |

| Virus Pathogen Resource (VIPR)/Zika virus | Database and analytical resource sponsored by NIAID, made publicly available. It supports research on pathogenic viral agents. It possesses data on genome and mature peptide annotations in the genomic database about the Zika. | https://www.viprbrc.org/ brc/home.spg? decorator=flavi_Zika |

| Zibra project | A project administered by an international group of researchers that used a trailer to collect material aimed at the sequencing of a thousand genomes in Brazil in order to provide important epidemiological information on the spreading of this disease in Brazil during the months of May and June 2016. | http://www.zibraproject.org/ |

| Zika Online Data-sharing Platform | An online platform of digital information of images of foetuses and newborns heads (with further clinical records associated with them) as a global resource of data sharing. It works in collaboration with different research groups from Brazil, US and UK. | https://www.wrh.ox.ac.uk/research/ zika-online-data-sharing-platform/form |

| Zika Open-Research Portal (Dave O'Connor Lab) | Created to facilitate collaborative research in real time in order to provide quicker response to the Zika emergency. On the portal, research of the Dave O'Connor Lab of the University of Wisconsin–Madison is available. The project includes raw data, comments and results of studies conducted with the University of Washington on three Indian rhesus monkeys (online laboratory notebook). | https://Zika.labkey.com/ project/home/begin.view? |

| ZikaPLAN (Zika Preparedness Latin American Network), ZIKAction and Zikalliance | Consortia financed by the European Commission that work in collaboration defining data harmonisation strategies and data sharing. | https://Zikaplan.tghn.org/http:// Zikaction.org/https: //Zikalliance.tghn.org/ |

| Zika Task Force | A network composed of members of the Global Virus Network (GNV) in response to the Zika epidemics. One of the actions was the setting up of a patient sera bank for distribution to interested scientists through the World Reference Center for Emerging Viruses and Arboviruses (WRCEVA) at the University of Texas Medical Branch. | http://gvn.org/programs/ Zika-virus-task-force/ |

Conclusion

The need to face the public health emergency of the Congenital Syndrome of the Zika, both at the Brazilian and at the international levels, revealed possibilities and limits of the sharing and opening of research data in the health area. The main conclusions of this analysis are summarised below.

- The emergency situation contributed to the wider circulation of research results on that PHEIC, especially by speeding up paper submission and publication processes, promoting collaborative networks of specialists, and making room for its dissemination through the media. This was motivated by the urgency of incorporating research results into strategies for combating the disease, assisting patients, and mobilising public opinion

- On the other hand, even with the strong appeal for the opening and sharing of research data, in order to tackle that public health emergency, there were significant obstacles to their practice. One obstacle was the lack of clear guidelines and explicit policies for incentivising researchers to open and share their data. The other one refers to the unequal conditions and terms of opening and sharing research data between research teams in countries with different situations of access to funding, research infrastructures and the means of science communication. This was expressed in the concern of Brazilian researchers to restrict their role as mere data providers and co-authors of papers published in international journals.

- Finally, it is necessary to acknowledge the role played by those affected by the disease in the provision of data relevant to the scientific understanding of the virus. Those groups are not part of the scientific field, its rules and means of communication, and, as such, are not among the preferential targets of the socialisation of the results of academic research.

Thus, we put forward some questions to be further explored: what type of strategies are required to incorporate the benefits of sharing research data on health in favour of affected and vulnerable social groups, as well as of peripheral countries in the global systems of science and technology? To what extent the opening and sharing of research data - in the context of the opening of science in the broadest sense - interfere in the reduction or in the increase of this inequality? We believe that new approaches, methodologies and metrics are required to incorporate these questions in all their complexity into the policies and strategies of different actors.

About the authors

Vanessa de Arruda Jorge is a Public Health Technologist at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ), Av. Brazil, 4365, Manguinhos, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. She received her Ph.D. from Post-Graduate Programme of Information Science, IBICT and the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, UFRJ. She can be contacted at: vanessaajorge@gmail.com

Sarita Albagli is a senior researcher at the Brazilian Institute of Information in Science and Technology, Rua Lauro Muller, 455 - 4.andar, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. She is also a professor at the Post-Graduate Programme of Information Science, IBICT and the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, UFRJ. She can be contacted at: sarita.albagli@gmail.com

References

- Albuquerque, P. C., Castro, M. J. C., Santos-Gandelman, J., Oliveira, A. C., Peralta, J. M. & Rodrigues, M. L. (2017). Bibliometric indicators of the Zika outbreak. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005132 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2T0JQrC)

- Araujo, K. M. de, Silva, C. H. da, Guimarães, M. C. S., Lins, R. A., & Neto, R. C. de S. A. (2017). A produção científica sobre Zika em periódicos de acesso aberto. [Scientific production on Zika in open access journals]. Revista Eletrônica de Comunicação, Informação & Inovação em Saúde, 11(Sup). http://dx.doi.org/10.29397/reciis.v11i0.1391

- Bardin, L. (2011). Análise de conteúdo [Content analysis]. (6th. ed.). Edições 70.

- Brazil. Ministério da Saúde. (n.d.). Guillain Barré: causas, sintomas, tratamentos e prevenção. [Guillain Barré: causes, symptoms, treatments and prevention]. http://portalms.saude.gov.br/saude-de-a-z/guillain-barre (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20190806012726/http://www.saude.gov.br/saude-de-a-z/guillain-barre)

- Briet, S. (1951) Qu'est-ce que la documentation? [What is documentation?] Éditions Documentaires Industrielles et Técnicas.

- Buckland, M. (1997). What is a "document"? Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 48(9), 804-809. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199709)48:9<804::AID-ASI5>3.0.CO;2-V

- Campos, G. S., Bandeira, A. C., & Sardi, S. I. (2015). Zika virus outbreak, Bahia, Brazil. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 21(10), 1885–1886. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2110.150847

- Diniz, D. (2016). Zika: do sertão nordestino à ameaça global. [Zika: from the northeastern hinterland to the global threat]. Civilização Brasileira.

- Diniz, D., & Carino, G. (2019, May 4). O silêncio sobre o Zika oprime as mulheres. [The silence about Zika oppresses women.]. El Pais.com. https://brasil.elpais.com/brasil/2019/05/04/opinion/1556979981_767326.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2uOzS4P)

- Dye, C., Bartolomeos, K., Moorthy, V., & Kieny, M. P. (2016). Data sharing in public health emergencies: a call to researchers. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 94(3), 158–158. http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.16.170860

- Gadelha, P., Fernandes, V. R., & Stabeli, R. (2017). O papel da Fiocruz no enfrentamento. [The role of Fiocruz in coping]. In Ministério da Saúde. Vírus Zika no Brasil: a resposta do SUS (pp. 73-80) http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/virus_zika_brasil_resposta_sus.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/328SI2B).

- GloPID-R (Global Research Collaboration for Infectious Disease Preparedness). (2018). Principles of data sharing in public health emergencies. http://www.glopid-r.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/glopid-r-principles-of-data-sharing-in-public-health-emergencies.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2T17X9C).

- Green, B., Cunningham, G., Ekblaw, A., & Kominers, P. (2017). Open data privacy. Berkman Klein Center. (Research Publication No. 2017-1; Harvard Public Law Working Paper No. 17-07.) http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2924751

- Henriques, C. M. (2017). A surpresa e o grito. [The surprise and the cry]. In Ministério da Saúde. Vírus Zika no Brasil: a resposta do SUS (pp. 15-25). http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/virus_zika_brasil_resposta_ sus.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/328SI2B).

- Johansson, M. A., Reich, N. G., Meyers, L. A., & Lipsitch, M. (2018). Preprints: an underutilized mechanism to accelerate outbreak science. PLOS Medicine, 15(4), e1002549. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002549

- Jorge, V. D. A. (2018). Abertura e compartilhamento de dados para pesquisa nas situações de emergência em saúde pública: o caso do vírus Zika. [Openness and sharing of data for research in emergency situations in public health: the case of the Zika virus]. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil).

- Lowrance, W. W. (2012). Privacy, confidentiality, and health research. Cambridge University Press.

- Machado-Silva, A., Guindalini, C., Fonseca, F. L., Pereira-Silva, M. V., & Fonseca, B. de P. (2019). Scientific and technological contributions of Latin America and Caribbean countries to the Zika virus outbreak. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 530. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6842-x

- Martins, M. de F. M. (2016). Análise bibliométrica de artigos científicos sobre o vírus Zika. [Bibliometric analysis of scientific articles on the Zika virus]. Revista Eletrônica de Comunicação, Informação e Inovação Em Saúde, 10(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.29397/reciis.v10i1.1096

- Open Knowledge Foundation. (n.d.). What is open data? Open Knowledge Foundation http://opendatahandbook.org/guide/en/what-is-open-data/

- Organisation For Economic Co-Operation And Development. (2007). OECD principles and guidelines for access to research data from public funding https://www.oecd.org/sti/inno/38500813.pdf

- Pirmez, C., Brandão, A. A., & Momen, H. (2016). Emerging infectious disease and fast-track publication: when public health gets priority over the formality of scholarly publishing. Memórias Do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, 111(5), 285–285. https://doi.org/10.1590/0074-02760160001

- Portaria No 1.813, de 11 de Novembro de 2015 que declara Emergência em Saúde Pública de importância Nacional (ESPIN) por alteração do padrão de ocorrência de microcefalias no Brasil. [Ordinance No. 1,813, of November 11, 2015 declaring Public Health Emergency of National Importance (ESPIN) due to changes in the pattern of occurrence of microcephaly in Brazil.] Brazil. Ministry of Health. http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2015/prt1813_11_11_2015.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/327sBsS).

- Sayão, L. F., & Sales, L. F. (2014). Dados abertos de pesquisa: ampliando o conceito de acesso livre. [Open research data: expanding the concept of open access]. RECIIS, 8(2), 76–92. https://www.reciis.icict.fiocruz.br/index.php/reciis/article/download/611/1252 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2QaJr5t)

- Wellcome Trust. (2016). Statement on data sharing in public health emergencies. Wellcome Trust. https://wellcome.ac.uk/what-we-do/our-work/statement-data-sharing-public-health-emergencies (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2SFXyBc).

- Wilkinson, M. D., Dumontier, M., Aalbersberg, Ij. J., Appleton, G., Axton, M., Baak, A., & Mons, B. (2016). The FAIR guiding principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data, 3, 160018. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18

- World Health Organization. (2015). Developing global norms for sharing data and results during public health emergencies. http://www.who.int/medicines/ebola-treatment/blueprint_phe_data-share-results/en/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/37A65dm).

- Zanluca, C., Melo, V. C. A. de, Mosimann, A. L. P., Santos, G. I. V. dos, Santos, C. N. D. dos, & Luz, K. (2015). First report of autochthonous transmission of Zika virus in Brazil. Memórias Do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, 110(4), 569–572. https://doi.org/10.1590/0074-02760150192