Dynamic aspects of relevance: differences in users' relevance criteria between selecting and viewing videos during leisure searches

Sarah Albassam and Ian Ruthven

Introduction. Previous research has investigated the dynamic use of relevance criteria at different stages of the search process. These previous studies have been focused on academic contexts with the result that little is known about the dynamic aspects of relevance criteria use in leisure contexts, specifically for video content. This paper examines the differences in relevance criteria at the stages of selecting and viewing videos for leisure purposes.

Method. Twenty-four participants were asked to search YouTube for leisure purposes followed by a semi-structured interview to elicit relevance criteria usage.

Analysis. Qualitative content analysis was applied on the data to discover relevance criteria applied in each search stage. Chi-squared tests were carried out to examine significant differences between the stages.

Results. Findings showed significant differences between selecting and viewing stages in term of the use of relevance criteria with some criteria being preferred in the selection stage while others are more important at the viewing stage of video interaction.

Conclusions. Understanding the changes in relevance criteria during the search process provides new insights about the dynamic aspects of relevance judgment and aids the design of information retrieval systems.

Introduction

Relevance is an important concept in information retrieval as retrieving relevant objects that satisfy the end user is considered the main goal of all information retrieval systems (Saracevic, 2016).

In the area of user relevance, there has been a special interest in the reasons users give to judge documents as relevant or not relevant, in other words the relevance criteria that users apply when making relevance judgment decisions (Saracevic, 2007). Previous research (Bateman, 1997; Schamber et al., 1990) has shown that relevance is dynamic and that user's relevance judgments can change over time. This evolution in relevance judgment is a reflection of the evolution in relevance criteria choices made by searchers during a search. The majority of the previous literature investigated relevance criteria are in academic or work-related contexts and mainly for textual content. Fewer studies have attempted to investigate relevance criteria of different media, e.g., image (Choi and Rasmussen, 2002), video (Yang, 2005), or in everyday life contexts (Xu, 2007).

Understanding how relevance criteria selections evolve as the search progresses and what criteria are more important at specific stages of the search can provide a deeper understanding of the dynamic aspects of relevance criteria and have implications for the design of information retrieval systems. Information retrieval systems could be more adaptive to the change in users' preferences of relevance criteria during the search and support users with useful information needed for relevance judgment decisions as they progress in their search. To enable this, we need to know how relevance criteria change during the search process.

Although we know a lot about relevance criteria in some contexts, we know little about the dynamic evolution of relevance criteria in leisure contexts and when the objects retrieved are videos. Relevance judgments of video content is more complicated than text or images as the users' needs are diverse and videos could be judged based on visual and audio features besides textual ones (Yang, 2005). Therefore, this study attempts to fill in this gap by investigating how participants might change their video relevance criteria selections at different stages of leisure searches.

The closest study is that of Yang (2005) who explored the use of relevance criteria for video retrieval. Although Yang's study shares similarities with this study in terms of the media retrieved, the studies' contexts are different. Yang's participants were academics, librarians and video editors who need videos as part of their job role, and the study did not examine the dynamic evolution of relevance criteria. On the other hand, Albassam and Ruthven (2018) attempted to partially fill the knowledge gap of applying relevance criteria when judging videos in a leisure context, however their study did not investigate the differences in relevance criteria at the different stages of selecting and viewing videos.

Previous text-based relevance criteria studies (Vakkaari and Hakala, 2000; Cole et al., 2017) reported differences in applying relevance criteria at different stages of the search process, an open question is to investigate the same issue in video leisure searches. Therefore this study will answer the following research question: what is the difference in employing relevance criteria between selection and viewing stages of video/leisure contexts searches and are these differences significant?

Related work

Relevance criteria dynamics

Relevance is known to be dynamic (Schamber et al., 1990). Many studies have investigated the change in criteria selection and importance among different search stages. A group of these studies (Bateman, 1997; Cole et al. 2017; Tang and Solomon, 2001; Vakkari and Hakala, 2000) have investigated the dynamic application of relevance criteria for students or academics while they were performing assignments or academic related searches. Bateman (1997) applied Kuhlthau's six stages of information seeking and in contrast to other studies of dynamic nature of relevance, reported no change in criteria choices among the stages. This might be because of the limited number of participants (Taylor et al., 2009) and the fact that the study focused only on highly relevant documents.

In the same academic context, Vakkari and Hakala (2000) investigated the use of relevance criteria applied by the students at different phases of the project: at the beginning, middle and final phases for both list of references and full text documents. The study identified six major categories of relevance criteria with twenty-five sub-categories. The findings showed that relevance criteria for references were more stable than relevance criteria for judging full text documents. In addition, for judging references, the study found topicality is the most important criterion at all stages of the search process. Recency experienced a decrease in its mentions as the search progress while interest in specific sources increased. For the full text documents, topicality was the most important criterion among all the stages while personal interest decreased as the search progress. Tang and Solomon (2001) conducted laboratory and naturalistic studies to investigate the change in relevance criteria between two search stages: citation and full text. The findings from both studies revealed an increase of mentions of the following criteria moving from citation to full text stages: importance, newness (novelty), and topical focus, while recency experienced a decrease in its mentions.

Similar to the previous works, Taylor et al., (2009) investigated the criteria that are important in eight different search stages adopted from the studies by Kuhlthau (1993) and Ellis and Haugan (1997). The study reported on a set of criteria that participants prefer to employ in all stages of the search process. They also reported that some criteria, e.g., most recent, gain more importance as the search progresses.

Recently, Cole et al., (2017) explored how relevance evolved as students' progress through Kuhlthau's stages. The study source of data were the students' assignments. Instead of focusing on relevance criteria to judge retrieved content, the study reported on how the participants constructed knowledge through search phases based on evolution in topical and psychological relevance. Three phases are mentioned: the associating phase in which students go from one idea to another associated idea; the translating phase in which students start building translations to the topic; and the verticalizing phase where students relate the topic information to their previous knowledge and beliefs. Study findings indicate that psychological relevance is constructed by the students in all three phases. Topical relevance only occurs in the verticalizing third phase.

Few studies have examined the dynamic aspects of relevance criteria for non-academic tasks such as self-generated search tasks. Savolainen and Kari (2006) and Xie and Benoit (2013) investigated relevance criteria applied by participants when judging links (result list) and web pages (full documents) during a web search. Savolainen and Kari found eighteen criteria and those criteria were similar for both stages. Topicality and specificity were highly used criteria in both stages. The study did not report on how relevance criteria change as the search progresses from one link or page to another. Xie and Benoit's results showed that many of the evaluation criteria selected for list and document evaluation are similar. These criteria include: scope, specificity, reputation, depth, credibility, cost, and language. The study also reported on a set of criteria that are uniquely mentioned in list or documents. For example, some of the criteria exclusively mentioned in document evaluation include: unique information, currency, accuracy, availability, length and type. Organization (or rank order) was only mentioned in list evaluation.

Other groups of studies investigated relevance criteria at different stages of image searches. For example, Choi and Rasmussen (2002) investigated the change in relevance criteria between two different stages of the search process: before the participants have the results of the search and after. Their findings indicated differences in the priority of applying the criteria with the importance of the appeal of information and accessibility increased as the search process progresses, whilst topicality decreases.

Hirsh (1999) examined the relevance criteria applied by young people when judging photos for a self-chosen sport celebrity in respect to a four week project related to a class assignment. Relevance criteria were examined at two stages of the search process: early stage (week 1) and at the end of the research process (week 3). Hirsh found differences in relevance criteria between the two stages. In the first stage, topicality was the dominant criterion. Approaching the end of the search process, topicality decreased and the students mostly mentioned the interesting criterion. This change in relevance criteria indicated a change in students' knowledge about their sport celebrity as they progress in the search process.

One study, by Pian, Khoo and Chang (2016) identified relevance criteria applied when searching information in health discussion forums for different purposes: searching information for their own health issue, searching for other people's health issue, and when browsing without a particular health issue in mind. The study investigated the use of relevance criteria at two stages of the search: result list and the full post content. The findings reported on differences in relevance criteria among the three search purposes at both stages of the search but not on differences between the two stages.

Leisure

Leisure is defined by Stebbins as 'uncoerced activity engaged in free time, which people want to do and in either a satisfying or fulfilling way (or both) use their abilities and sources to success at this' (2007, p.4). Stebbins distinguished between three forms of leisure: serious, casual and project-based. Serious leisure requires special skills, previous knowledge and experience while casual leisure consists of short entertaining activities which do not require special training. Project-based leisure is a type of leisure between the aforementioned forms of leisure. It involves short and occasional activities which needs some planning or skills.

Previously, information behaviour studies mainly focused on task-based scenarios (Elsweiler et al., 2011; Hartel, 2003) with the result that little is known about information behaviour in leisure contexts. Later studies emerged to investigate leisure information behaviour to examine whether the qualities of information change when moving from task-based scenarios in work contexts to leisure contexts. Hartel (2006) investigated the information needs and seeking aspects of serious leisure activities such as cooking gourmet. Studies which explored information behaviour and needs for casual-leisure searches also emerged. Elsweiler et al. (2011) reported on two studies of casual-leisure information seeking. The first explored the participants' information needs and motivations in the context of viewing television and in the second, users' tweets on Twitter were used to investigate users' needs for various casual-leisure scenarios. The findings from both studies confirm that the information needs in casual-leisure scenarios are unclear and that the motivations for such searches are rarely related to finding information.

Some research examined the use of relevance criteria for recreational reading. Reuter (2007) examined relevance criteria applied by children when selecting books from a digital library. The study has also reported the differences in applying relevance criteria among three stages of the search process: selecting (result list), judging (surrogate) and sampling (full text). The findings showed that novelty had high mentions in the selecting stage while accessibility peaked in the judging stage. Similar to Reuter, Koolen et al. (2015) investigated relevance criteria as expressed in the users' feeds of Library Thing discussion forum. Several relevance aspects were identified such as content, accessibility, novelty, engagement and familiarity. The findings revealed that content was the most frequently mentioned relevance criterion for a book request, followed by familiarity.

Mikkonen and Vakkari (2016) investigated fiction readers' interest criteria when selecting books in two different library catalogues. The findings indicated five main dimensions of interest criteria: familiarity, bibliographical information, content, engagement and sociocultural criteria. Familiarity and bibliographical information are the most frequently mentioned interest criteria for selecting novels in both library catalogues. In contrast to Reuter (2007) and Koolen et. al. (2015), the concept of interest criteria is used in this study instead of relevance criteria because Mikkonen and Vakkari argue that relevance is not suited as a concept for recreational reading. The authors interpret relevance as topical relevance ignoring the users' emotions and assume a topical relation between users' needs and the retrieved information. Saracevic's (2007) model of relevance acknowledges broader aspects of relevance which goes beyond the topical dimension and includes situational, cognitive and affective aspects of relevance. For the present study, relevance is a more useful and comprehensive concept. In this research context, user's judgments decisions' regarding the retrieved videos for leisure purposes are not only based on interest, other criteria such as the quality aspects of the videos and topical relevance are important as well.

Similar to the current study, Yeh (2016) explored the casual-leisure information behaviour of viewing videos online. Users' casual leisure information behaviour were investigated at three phases of the search: pre-viewing, viewing and post-viewing which result in a proposed framework of casual leisure video viewing processes and information behaviours. While Yeh's study share similarities with this study in terms of the context, the focus is different. Yeh's study investigated the motivations that trigger casual leisure video search and the information behaviour activities while viewing videos. In contrast, this study focuses on the differences in relevance criteria applied between stages of the search.

Literature summary

The majority of previous studies investigating the dynamic aspects of the relevance judgment process were longitudinal and the search task was for students conducting assignments or research project. Furthermore, the vast body of dynamic use of relevance criteria literature were on searching for textual information rather than audio or visual information. The focus of the previous related studies in leisure contexts are on the users' needs and motivations rather than relevance criteria. Therefore, this study attempts to shed light on the dynamic aspects of video relevance criteria in leisure contexts to fill this knowledge gap.

Methods

Overview

Recorded search sessions were conducted followed by semi-structured interviews. YouTube was chosen as the video retrieval system in this study. Other video retrieval systems were considered such as Dailymotion and Bing, but a decision was made to restrict the system used to YouTube because it is the most popular system, ranked second globally after Google. It is widely used by over a billion users and with a huge variety of videos. This study was granted approval from the Departmental Ethics Committee.

Participants

Twenty-four YouTube users participated in the study. Of the participants, thirteen were males and eleven were females. The age range is between 19 and 58 with an average age of 27.5. Among the participants, twelve were undergraduate students, six master students, four university staff, one college student and one PhD student. They were studying different disciplines. Around half of the participants reported using YouTube several times a day, ten of them search from one to three times a week and only three reported that they search once or twice a month. Participants were recruited through flyers distributed in different places in the campus and £5 was offered as compensation of their effort.

Procedure

Participants were invited to a private room in the university. Initially, the study purpose and procedure was explained verbally and a handout provided to the participant. The participant signed a consent form to indicate agreement to participate in the study. To prepare the participant to the leisure search session, a short chat about the participant's motivations for viewing videos and the types of video that the participant would normally watch during free time proceeded the actual search session. The participant was provided the following search scenario and asked to search and browse YouTube as normal:

Imagine you got 20 minutes spare time and you decided to watch some videos during this time to entertain yourself. You might recall some of your recent searching or browsing for videos on YouTube that you did for leisure or entertainment and reply it. The search topic should be personal and not related to any course assignments. There is no restriction on how you initiate your searches. e.g., starting by typing query, YouTube suggestions and popular videos, or your subscriptions channels.

All search sessions were recorded using Camtasia screen recording tool. On completion of the search session, the first author returned to the room and played back the session. A semi-structured interview was conducted in which the participant was able to watch back the search session in whole and describe the reasons behind their relevance judgment decisions on each video for both selection and viewing stage. Selection stage is where participants are evaluating the videos in the search result list or browsing videos in the home page of YouTube or a specific channel. For each video the participant decided to click on, she was asked what attracted her to click on this video and what made her predict that the video would be relevant? The viewing stage represents the actual viewing of the video. For each video the participant viewed, they were asked what they thought about the video after watching it. In following this approach the participant avoided the distraction that might be caused if questions were asked during the viewing of their videos. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed.

Data analysis

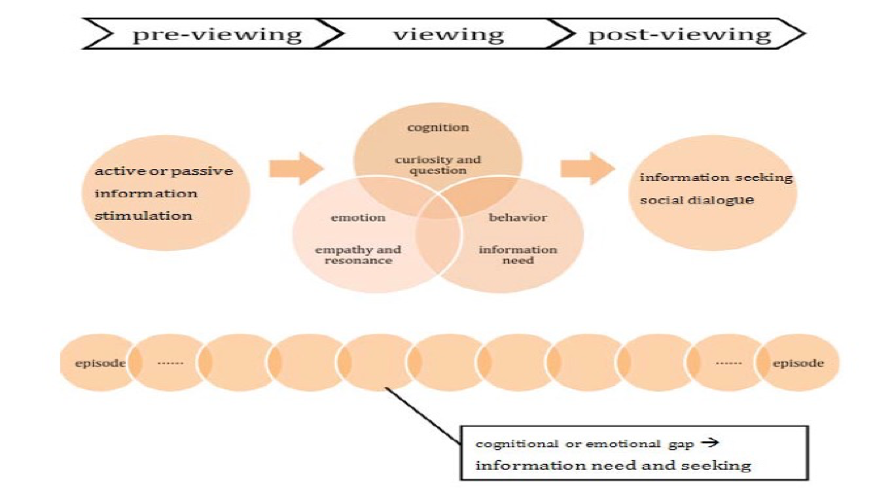

Data analysis began with careful reading of the transcripts, noting utterances that reflected relevance criteria mentions. The stages of the search process applied in our study followed Yeh's framework (Yeh, 2016) of casual-leisure video viewing processes and information behaviour (Figure 1). This framework was chosen because it shares similarities with this study in terms of the context (casual leisure video viewing). This study refers to pre-viewing stage as the selection stage. As there were no relevance judgments after viewing the videos, our analysis only focused on the selection and viewing stages.

Figure 1: Casual-leisure video viewing framework (Yeh, 2016)

Each utterance was coded based on the coding scheme developed by Albassam and Ruthven (2018) with the possibility of adding new codes when needed. One new criterion - Layout/presentation - was added to the coding scheme which is defined as the extent to which presentation, delivery and clarity of the information are factors in participant's relevance judgment. Each mention of relevance criteria was assigned a single criteria code and a code to note which search stage: selection or viewing. Video recordings were viewed to get a better understanding of the session but the main analysis depends on the transcripts. The coding scheme is shown in the appendix.

To investigate the differences in applying relevance criteria between the selection and viewing stages, a count of mentions of each criterion are provided for each stage (Table 3). Chi-squared tests are applied to examine whether the variance in number of mentions of each criterion between the two stages is statistically significant. Thus, Chi-squared tests were used to investigate whether a relationship exists between the stage of the search and relevance criteria applied and to ensure that the relationship is a meaningful relationship and not due to chance.

Findings

In total, 818 mentions of relevance criteria were revealed by the interviews' transcript analysis. The total number of videos watched was 165 videos with an average of seven videos per participant (min 3 max 16, standard deviation 3). Participants searched for various topics including: songs and music, TV or YouTube shows, movie trailers, celebrities, video games, comedy clips, animals' videos, sports, travel and tourism, motivational speeches and news. The findings are structured as follows: firstly differences in relevance criteria between selecting and viewing search stages were investigated. Then the change in relevance criteria between the start and end of the sessions was investigated.

Relevance criteria at different search stages

Selection stage

The selection stage precedes the actual viewing of the video where participants select videos to watch from YouTube home page, specific channel page or from the search result list of their queries. Search sessions started by either searching for specific topic or browsing videos on the home page. Three participants logged in to their accounts and browsed their subscriptions.

The data showed that participants mainly select the relevance of a video based on topicality which was the most dominant criterion in this stage, accounting for nearly one-fifth of the mentions. The second most mentioned criterion in the selection phase is familiarity. Topicality and familiarity of the video are predicted from the title or the thumbnail. Sometimes participants recognise familiarity with the source from the channel name as well, for example, 'and also I recognize the uploader as well' (participant 16).

Familiar videos are preferred in some cases to guarantee enjoyment and to save participant's time:

I do not click on videos from people that I do not know. If its news, or world events, then that's okay, watching Sky News or CNN. But that's just on a kind of event to event news basis. Usually I stick with what I know, just because I don't want to waste my time (participant 17).Participants also followed recommendations provided by friends, YouTube or social media sites. The Recommended video criterion acquired 9.8% of the total mentions in this stage. Examples: 'Because it was recommended in this section. So I just clicked on it' (participant 23).

Participants may select videos to watch based on their novelty 'but I hadn't watched it, so I decided I would watch it just now' (participant 17).

People appearing in the video was another reason for selecting videos. For example 'choose the Lady Gaga one' (participant 1). Novelty and People appeared in the video each acquired 8.8% of the overall mentions of relevance criteria.

During the selection stage, participants also give attention to the source providing the video and its quality. For example, 'It's Warner Bros. which is a movie company, so you know it's real, it's not a fake trailer or anything' (participant 23).

There are some criteria that are exclusively mentioned in the selection stage. For example, the appeal of the thumbnail of the video, visual appeal 'and the picture made it look really funny because she was pulling a face or something' (participant 22). Other criterion only mentioned in this stage include: rank order, recommended videos and serendipity/curiosity.

The full list of relevance criteria in the selection stage ordered by their number of mentions is provided in Table 1.

| Criterion | % of mentions | No. of mentions | Criterion | % of mentions | No. of mentions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| topicality | 1.9 | 8 | rank order | 18.2 | 75 |

| familiarity | 1.9 | 8 | version | 10.9 | 45 |

| recommended video | 1.7 | 7 | serendipity & curiosity | 9.7 | 40 |

| people | 1.0 | 4 | content quality | 9.0 | 37 |

| novelty | 1.0 | 4 | genre | 8.5 | 35 |

| source quality | 0.7 | 3 | language | 7.1 | 29 |

| visual appeal | 0.5 | 2 | habit | 5.1 | 21 |

| popularity | 0.2 | 1 | technical quality | 4.6 | 19 |

| length | 0.2 | 1 | cinematography | 3.9 | 16 |

| recency | 0.2 | 1 | sound & voice | 3.6 | 15 |

| background | 0.2 | 1 | unusualness | 3.4 | 14 |

| coverage | 0.2 | 1 | verification | 3.2 | 13 |

| affectiveness | 0.2 | 1 | time constraint | 2.4 | 10 |

Viewing stage

During viewing stage, affectiveness was the most dominant criterion with approximately one-fifth of the overall mentions of relevance criteria in this stage. The effect that the video selected made on the participant's feeling in negative or positive way is important to the participants at this stage. For example, participants might express the positive effect of the video by comments such as 'I find it interesting. It's emotionally engaging for me' or negatively 'And then I got bored with that' (participant 3).

In the viewing stage, Topicality continued to be an important criterion with 10.5% of mentions. Besides being on topic, participants pay attention to the content quality of the video. For example, a participant might select a video on specific topic but then get annoyed by the poor quality of the information provided in the video 'It was too informal, too unprofessional. It was kind of just mashed up. There was no proper information, it was just clips' (participant 17).

Whilst novelty was important in selecting videos, it could be a crucial criterion in discarding a video after starting to watch it, for example, 'For this one, it wasn't even a very funny one, so as soon as I recognized that I had definitely seen it before, I clicked away' (participant 2).

During viewing stage, layout/presentation of the information as appeared in the video was mentioned as a criterion for relevance judgment. For example,

Apart from the video, it's just the layout. It says that it is inside the aircraft, so it shows you where the aircraft is based. And then actually how to get into the aircraft, and then it shows you the different compartments. (participant 13)

This criterion is exclusively mentioned in the viewing stage.

Around 6% of the mentions of relevance criteria during the viewing stage related to the Coverage aspects of the information provided in the video, for example, 'In depth, but like not exaggerated, yes. This is the office, it is connected to that, that, that. Taking you through the whole aircraft, but in a very reasonable time' (participant 13).

Participants mentioned a wide variety of additional criteria in this stage, such as technical quality and cinematography. Table 2 provides the full list of relevance criteria in the viewing stage ordered by the number of mentions.

| Criterion | No. | % | Criterion | No. | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| affectiveness | 88 | 21.6 | unusualness | 14 | 3.4 |

| topicality | 42 | 10.3 | source quality | 7 | 1.7 |

| content quality | 40 | 9.8 | language | 7 | 1.7 |

| novelty | 33 | 8.1 | recency | 6 | 1.5 |

| layout | 25 | 6.1 | version | 5 | 1.2 |

| coverage | 24 | 5.9 | verification | 4 | 1 |

| background | 20 | 4.9 | familiarity | 3 | 0.7 |

| technical quality | 18 | 4.4 | genre | 3 | 0.7 |

| length | 18 | 4.4 | habit | 2 | 0.5 |

| people | 15 | 3.7 | popularity | 1 | 0.2 |

| cinematography | 16 | 3.9 | time constraint | 1 | 0.2 |

| sound and voice | 15 | 3.7 |

Differences between selection and viewing phases

Table 3 specifies the differences in the number of mentions of each relevance criterion between the two search stages. A Chi-squared test was conducted to examine the differences in relevance criteria mentions between selection and viewing stages. The null hypothesis to be tested is "there is no significant difference in using relevance criteria between the selection and viewing stages". Similar to previous studies (Maglaughlin and Sonnenwald, 2002; Savolainen and Kari, 2006) the share of relevance criteria are uneven with some criteria being highly uses while others were marginal. Marginal criteria with low frequency count (less than ten) were not included in the test (verification, time constraint, serendipity, rank order, habit and genre). Taken as a whole, the test result revealed a highly significant difference in applying relevance criteria between selecting and viewing stages, Χ2 (20) = 325.103, p < 0.001 and the null hypothesis was rejected.

| Relevance criteria | Selecting | Viewing | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria related to the information content of the video | |||

| coverage | 13 | 24 | 37 |

| topicality | 75 | 42 | 117 |

| recency | 15 | 6 | 21 |

| genre | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| length | 16 | 18 | 34 |

| people in the video | 37 | 15 | 52 |

| Criteria related to the participant's previous experience and background | |||

| background experience or personal memories | 14 | 20 | 34 |

| novelty | 35 | 33 | 68 |

| familiarity | 45 | 3 | 48 |

| Criteria related to the participant's beliefs and preferences | |||

| affectiveness | 10 | 88 | 98 |

| serendipity and curiosity | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| habit | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| time constraint | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Criteria related to the quality aspects of the video or the source providing the video | |||

| quality of source | 29 | 7 | 36 |

| content quality | 4 | 40 | 44 |

| technical quality | 1 | 18 | 19 |

| layout | 0 | 25 | 25 |

| Criteria related to audio/visual features of the video | |||

| cinematography | 1 | 16 | 17 |

| visual appeal | 21 | 0 | 21 |

| sound and voice | 1 | 15 | 16 |

| Criteria related to the accessibility of the video | |||

| language and subtitles | 3 | 7 | 10 |

| version | 8 | 5 | 13 |

| Criteria related to other information within the environment | |||

| verification | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| unusualness | 1 | 14 | 15 |

| Criteria related to other people's opinions or YouTube's recommendations | |||

| rank order | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| popularity | 19 | 1 | 20 |

| recommended video | 40 | 0 | 40 |

| Total | 411 | 407 | 818 |

Some criteria are more important at the selection stage while others have more mentions in the viewing stage. A follow-up post hoc test was performed following the calculating residuals approach to identify the criteria which contribute to the significant variance between the two search phases (Field, 2013; Sharpe, 2015). A Bonferroni correction is suggested when the number of comparisons is high (comparing selecting and viewing stages for twenty-one relevance criteria) to avoid Type I error (Macdonald and Gardner, 2000; Sharpe, 2015).

A Bonferroni correction was conducted and the corrected alpha was α = 0.002 Table 4 shows the criteria whose use was statistically significant between the two stages. Throughout the stages, some criteria (such as novelty and length) remain steady, others changed slightly but did not contribute to the significant difference between the stages.

| Criterion | Χ2 | No. of mentions |

|---|---|---|

| Selection stage | ||

| recommended video | 43.16 | 40 |

| familiarity | 40.20 | 45 |

| visual appeal | 22.09 | 21 |

| popularity | 17.06 | 19 |

| source quality | 15.21 | 29 |

| topicality | 11.83 | 75 |

| people in the video | 10.50 | 37 |

| Viewing stage | ||

| affectiveness | 68.89 | 88 |

| content quality | 30.36 | 40 |

| layout | 25.20 | 25 |

| technical quality | 15.21 | 18 |

| cinematography | 13.18 | 16 |

| sound | 12.18 | 15 |

| unusualness | 11.16 | 14 |

Moving from the selection to the viewing phase, the number of mentions of familiarity, topicality, source quality and popularity significantly dropped. Criteria that were only mentioned in the selection phase were recommended video and visual appeal.

Conversely, criteria which shows a significant increase in the number of mentions are affectiveness, content quality, technical quality, cinematography, sound and unusualness. Layout criterion was only mentioned in the viewing stage.

It is expected that some of the criteria such as technical quality, cinematography, etc. will have more mentions in the viewing stage as the participant needs to examine the full video to judge it based on these criteria. The participant could predict relevance based on these criteria at the selection stage but will not be determinate until examination of the video itself. On the other hand, other criteria such as source quality and popularity mentioned more in the selection stage as participants predict relevance based on them.

Relevance criteria changes between the start and end of the sessions

The previous sections investigated relevance criteria for each video viewed in the search session at two stages: before viewing the video (selection stage) and while viewing the video (viewing stage). As participants watch several videos during their leisure search session, they go through several episodes of selection-viewing stages.

In this section, we will further investigate whether relevance criteria change between the beginning and the end of the search sessions. The goal here is to examine whether the mentions of relevance criteria used at the end of the search sessions are similarly distributed to those mentions of relevance criteria at the beginning of the search sessions. This will indicate whether the participants (as a group) were consistent in applying their relevance judgment criteria through the session. Understanding how participants behave in the search session is important for information retrieval developers as sessions is a key element that developers focus on (He et al., 2002; Neelima and Rodda, 2016).

To achieve this goal, criteria mentioned at the first and last videos (at both selection and viewing stages) for each session are extracted from the interviews. As just the first and last videos were taken, the sample size became small. The null hypothesis to be tested is: 'there are no differences in applying relevance criteria between the beginning and end of the search sessions'. Fisher's exact is an alternative to Pearson Chi Squared test which is recommended for small samples (Field, 2013). Fisher's exact statistical test was conducted to investigate the stability of relevance criteria between the beginning and the end of the sessions for selection and viewing criteria data sets. The test showed no significant differences between applying relevance criteria at these two points of the sessions for both selection (p= 0.669, Fisher's Exact test) and viewing (p= 0.469, Fisher's Exact test) data sets.

This result indicated that participants were consistent in applying relevance criteria during the search session and that there were no preferences for particular criteria between the beginning and end of the session. This implies that retrieval systems in leisure contexts are not required to support the user differently between the beginning and end of the session.

Discussion

Relating the findings to the literature

This paper investigated the relevance criteria participants apply in the selection and viewing stages of the search process when searching videos in leisure contexts with the goal of providing additional insights on the dynamic use of relevance criteria.

The findings showed that there is a significant difference in applying relevance criteria between selection and viewing stages. This aligns with some of the previous dynamic relevance criteria studies (Reuter, 2007; Tang and Solomon, 2001; Xie and Benoit, 2013).

The study found that criteria such as topicality and familiarity play an important role in the participant's initial relevance judgment at the selection stage. Participants are first attracted to videos which are familiar to them or from familiar channels. In this early stage, participants are also attracted to videos with appealing thumbnails and popular videos. Mikkonen and Vakkari, (2016) and Kooleen et al. (2015) have also found that familiarity is the most mentioned interest criteria for selecting novels.

As the search progresses, the importance of familiarity decreased for the sake of affectiveness, which became the most dominant criterion at the viewing stage. This in alignment with a previous study about recreational reading, which found familiarity to be less prevalent at later stages of the search (Reuter, 2007). Participants became more specific and apply other criteria regarding the content of the video and how the information was presented at this stage. In addition, audio/visual criteria such as cinematography, sound and technical quality increased significantly.

These findings indicate that although participants might initially base their judgments on the topic of the video or their familiarity with the video or the channel, as they progress in the search other criteria such as affectiveness and quality content became more crucial. Affectiveness was the criterion with the highest significant change between the two stages. This reinforces Mikkonen and Vakkari's work (2016), which found that user's previous knowledge and novels' title are the initial triggers to users interest in a novel, content description contributes to the final decision for selecting a novel.

In alignment with Xu (2007), novelty was found to be an important criterion for non-problem solving task at the selection and viewing stages of the search. Novelty remains steady while moving between selection and viewing stages in our study. Previous studies did not agree about the development of the importance of novelty among search stages. Tang and Solomon's study (2001) found novelty to be more important at later stages while Reuter (2007) reported an increase in mentions of novelty at earlier stages of the search

Based on previous research, it was expected that topicality would experience a decrease in the number of mentions moving from selection to viewing stages. Our results confirm the findings from previous studies, topicality became less important as the participants move to the viewing stage.

Besides examining the change in relevance criteria between selection and viewing stages for each video, the study examined the use of relevance criteria between the beginning and end of the search sessions. The findings showed stability in applying relevance criteria between the start and end of the sessions. Some of the previous works (Hirsh, 1999; Taylor, 2013) in an academic-related context found changes in applying relevance criteria as the session progresses and relate this to change in user's cognitive state. As users progress in their searches, gain more understanding of the search task and topic. This is not always the case in leisure search. This result indicates that leisure search context is different, participants do not necessarily start their searches with a vague cognitive state and unfamiliarity of the search tasks. As in a leisure context, the goal is not always to fill in knowledge gap, the main aim of the search is entertainment. Even when the participants search for specific topics (e.g., airlines crafts, surfing videos) they are still applying a finite set of criteria as they progress in their search sessions.

Implications for system design

Video retrieval systems such as YouTube provide some search filters that support the relevance criteria that users employ to judge the relevance of the videos. Data showed participants have preferences based on the length of the video, popularity, recency and the technical quality (high definition versions). YouTube offers filters to search for videos that are less/greater than 20 minutes, to rank the result list by date of upload and also facilitates the search for videos in a specific format (high definition for example).

Similar to previous studies which found that advanced search options are rarely used (Choi, 2010) and their use is not intuitive (Taylor et al., 2009), none of the participants in the study apply any of these filters even when they met their relevance criteria. It might be that participants are not aware of their existence or they were hidden. The study confirms Choi's findings that such filters should be easily located on the main search page to encourage the users to get benefits from them. Maybe it is worth video search engines identifying the relevance criteria that are crucial to the user based on his search history, and provide information about suitable advanced search tools. It might be a small advert at the beginning of the video or a pop up message that shows in brief what search filter would enhance search result and is suitable to the searchers' criteria.

As the findings show that in leisure searches participants mostly showed consistency in applying relevance criteria between the beginning and end of the session. This finding indicates that video retrieval developers might treat a session as the basic unit of analysis rather than a user profile in general. Furthermore, the findings showed low mentions of serendipity/curiosity as a relevance criterion. It is an open question to explore whether serendipity is not required by users in leisure searches or the video retrieval system are not supporting the users enough to serendipitous encountering of interesting videos. This study did not answer this question, however it suggests the investigation of the role of serendipity in video leisure search and how could it be improved.

Limitations

This study also has its limitations. A limitation of the methodology can be found in the time constraint of the search sessions, some participants tended to avoid selecting long videos as they want to provide more videos in their sessions. To mitigate the effect of time constraint and prevent its influence on the study results, when participants mention the length of the video as a reason for selection, they were asked whether the study settings was the reason or whether they will have the same decision if they were not doing the search for a study experiment. Mentions of length because of the study's time limit were not counted as mentions of length criterion.

Furthermore, in this study all the participants' searches were conducted by a single desktop computer. YouTube's recommendation algorithm is not as good as when a person is using his personal computer. The place of conducting the search session is not the normal place where the participants usually search. To mitigate the effect of the study location, the participants were left alone to search in a private room and at the end of the interviews they were asked whether they experienced any difficulties because of the place and whether they have searched similar to what they would do normally. None of the participants mentioned inconvenience because of the place. Moreover, the pre-search chatting attempted to help in putting the participants in the study context by letting them describe what they usually search for on YouTube for leisure purposes.

Further limitations can be found in the participants' sample used in this study. Participants were of similar age (young) and similar level of education (well educated). Relevance criteria might be affected due to these factors.

Conclusion

The main contribution of the study was to investigate how users' selections of relevance criteria changes through progressing in the search process for video/leisure contexts searches. Investigating the dynamic aspects of relevance criteria in leisure/video contexts inform the design of video retrieval systems. Previous works of dynamic use of relevance criteria were mainly focused on academic and work related context and mainly for text retrieval.

Our statistically significant results suggest that criteria selections changed at different stages of the search process. Criteria such as recommended video and familiarity are crucial in the selection stage while others such as affectiveness and content quality are more important at the viewing stage. As this study focused on the dynamic use of relevance criteria in leisure search in general, future research might investigate in more depth the differences in dynamic applying of relevance criteria among different leisure topics.

About the authors

Sarah Albassam is an Assistant Professor in King Saud University, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia. She received her PhD degree in Computer and Information Sciences from the University of Strathclyde in 2018. She can be contacted at salbassam@ksu.edu.sa

Ian Ruthven is Professor in information seeking and retrieval in the Department of Computer and Information Sciences at the University of Strathclyde, 16 Richmond St., Glasgow G1 1XQ. He can be contacted at ian.ruthven@strath.ac.uk

References

- Albassam, S. A. A., & Ruthven, I. (2018). Users' relevance criteria for video in leisure contexts. Journal of Documentation, 74(1), 62–79. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-06-2017-0081 (https://pureportal.strath.ac.uk/files/68008880/Albassam_Ruthven_JD2017_Users_relevance_criteria_for_video_in_leisure_contexts.pdf.)

- Bateman, J. (1997). Changes in relevance criteria: a longitudinal study. Proceedings of the ASIS Annual Meeting, 35, 23–32.

- Choi, Y. (2010). Effects of contextual factors on image searching on the Web. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 61(10), 2011–2028. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21386

- Choi, Y., & Rasmussen, E. M. (2002). Users' relevance criteria in image retrieval in American history. Information Processing & Management, 38(5), 695–726. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4573(01)00059-0

- Cole, C., Beheshti, J., & Abuhimed, D. (2017). A relevance model for middle school students seeking information for an inquiry-based class history project. Information Processing & Management, 53(2), 530–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2016.10.002

- Ellis, D., & Haugan, M. (1997). Modelling the information seeking patterns of engineers and research scientists in an industrial environment. Journal of Documentation, 53(4), 384–403. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000007204

- Elsweiler, D., Wilson, M. L., & Lunn, B. K. (2011). Understanding casual-leisure information behaviour. In A. Spink & Heinström, J. (Eds.), New directions in information behaviour (pp. 211–241). Emerald Group Publishing.

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Hartel, J. (2003). The serious leisure frontier in library and information science: hobby domains. Knowledge Organization, 30(3), 228-238. https://doi.org/10.5771/0943-7444-2003-3-4-228

- Hartel, J. (2006). Information activities and resources in an episode of gourmet cooking. Information Research, 12(1), paper 281. http://InformationR.net/ir/12-1/paper282.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6zg3bQIDM)

- He, D., Göker, A., & Harper, D. J. (2002). Combining evidence for automatic Web session identification. Information Processing & Management, 38(5), 727–742. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4573(01)00060-7

- Hirsh, S. (1999). Children's relevance criteria and information seeking on electronic resources. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 50(14), 1265–1283. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(1999)50:14%3C1265::AID-ASI2%3E3.0.CO;2-E

- Koolen, M., Bogers, T., van den Bosch, A., & Kamps, J. (2015). Looking for books in social media: an analysis of complex search requests. In A.Hanbury, G. Kazai, A. Rauber & N. Fuhr (Eds.), Proceedings of European Conference on IR Research, ECIR 2015. (pp. 184–196). Springer (Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 9022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16354-3_19

- Kuhlthau, C. C. (1993). Seeking meaning : a process approach to library and information services. Ablex.

- Macdonald, P. L., & Gardner, R. C. (2000). Type I error rate comparisons of post hoc procedures fori jchi-square tables. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 60(5), 735–754. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F00131640021970871

- Maglaughlin, K. L., & Sonnenwald, D. H. (2002). User perspectives on relevance criteria: a comparison among relevant, partially relevant, and not-relevant judgments. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 53(5), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.10049

- Mikkonen, A., & Vakkari, P. (2016). Readers' interest criteria in fiction book search in library catalogs. Journal of Documentation, 72(4), 696–715. https://doi.org/10.1108/JDOC-11-2015-0142

- Neelima, G., & Rodda, S. (2016). Predicting user behavior through sessions using the web log mining. In 2016 International Conference on Advances in Human Machine Interaction (HMI), Doddaballapur (pp. 1–5). Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. https://doi.org/10.1109/HMI.2016.7449167

- Pian, W., Khoo, C. S., & Chang, Y.-K. (2016). The criteria people use in relevance decisions on health information: an analysis of user eye movements when browsing a health discussion forum. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(6), e136. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5513

- Reuter, K. (2007). Assessing aesthetic relevance: children's book selection in a digital library. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(12), 1745–1763. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20657

- Saracevic, T. (2016). The notion of relevance in information science: everybody knows what relevance is. But, what is it really? Synthesis Lectures on Information Concepts, Retrieval, and Services, 8(3), pp. 109. https://doi.org/10.2200/S00723ED1V01Y201607ICR050

- Saracevic, T. (2007). Relevance: a review of the literature and a framework for thinking on the notion in information science. Part III: Behavior and effects of relevance. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(13), 2126–2144. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20681

- Savolainen, R., & Kari, J. (2006). User-defined relevance criteria in web searching. Journal of Documentation, 62, 685–707. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410610714921

- Schamber, L., Eisenberg, M. B., & Nilan, M. S. (1990). A re-examination of relevance: toward a dynamic, situational definition. Information Processing & Management, 26(6), 755–776. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4573(90)90050-C

- Sharpe, D. (2015). Your Chi-square test is statistically significant: now what? Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 20, Article 8. https://doi.org/10.7275/tbfa-x148

- Stebbins, R. A. (2009). Leisure and its relationship to library and: information science: bridging the gap. Library Trends, 57(4), 618–631. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.0.0064

- Stebbins, R. A. (2007). Serious leisure: a perspective for our time. Transaction Publishers.

- Tang, R., & Solomon, P. (2001). Use of relevance criteria across stages of document evaluation: On the complementarity of experimental and naturalistic studies. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 52(8), 676–685. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.1116

- Taylor, A. (2013). Examination of work task and criteria choices for the relevance judgment process. Journal of Documentation, 69(4), 523–544. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-12-2011-0054

- Taylor, A., Zhang, X., & Amadio, W. J. (2009). Examination of relevance criteria choices and the information search process. Journal of Documentation, 65, 719–744. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410910983083

- Vakkari, P., & Hakala, N. (2000). Changes in relevance criteria and problem stages in task performance. Journal of Documentation, 56(5), 540–562. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000007127

- Wang, P., & White, M. D. (1999). A cognitive model of document use during a research project. Study II. Decisions at the reading and citing stages. Journal of The American Society for Information Science, 50(2), 89–114. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(1999)50:2%3C98::AID-ASI2%3E3.0.CO;2-L

- Xie, I., & Benoit, E. (2013). Search result list evaluation versus document evaluation: similarities and differences. Journal of Documentation, 69(1), 49–80. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220411311295324

- Xu, Y. (2007). Relevance judgment in epistemic and hedonic information searches. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(2), 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20461

- Yang, M. (2005). An exploration of users' video relevance criteria. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA)

- Yeh, N. (2016). The role of online videos in undergraduate casual-leisure information behaviors. Global Journal of Human Social Science: C Sociology & Culture, 16(5), 7-13. https://publications.waset.org/10004865/pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200221114140/https://publications.waset.org/10004865/pdf

How to cite this paper

Appendix: Definitions of criteria

| Criterion | Definition |

|---|---|

| coverage | The extent to which information gained from the video is detailed and has sufficient depth, specific to the participant's needs, provides a summary or provides a sufficient variety or volume of information. |

| topicality | The extent to which information provided in the video matches the participant's search topic or interest. |

| recency | The extent to which the video is recent and this is important to the user. |

| genre | The extent to which the genre of the video (e.g., anime, historical, comedy) is a factor in the relevance judgement. |

| length | The extent to which video length (duration) is a factor in the participant's judgement. |

| people in the video | The extent to which the participant's judgement is influenced by people appearing in the video (TV host, singer, actor, band, YouTuber or guest, etc.). |

| background experience or personal memories | The degree of knowledge with which the participant approaches the video, as indicated by mentions of background or experience or personal memories. |

| novelty | The extent to which the video or the information presented in the video is novel to the participant, which means it is new based on previous interests. |

| familiarity | The extent to which the participant is familiar with the exact video or similar videos or is familiar with the source providing the videos. |

| affectiveness | The extent to which the participant exhibits an affective or emotional response to video; the video provides the participant with pleasure, enjoyment or entertainment or alternatively disappointment or other negative experiences. |

| serendipity or curiosity | The extent to which selecting the video is dependent on personal curiosity without having a previous interest in the topic or depending on the accidental discovery of useful or interested information while searching for other information. |

| habit | The extent to which the participant is familiar with the video and watches it in a repetitive manner or as part of another habit. |

| time constraint | The extent to which time constraint is a factor in participant' judgement. |

| quality of source | The extent to which participant's judgement of the quality of the information is influenced by the source providing the video and whether the source is well known or trusted. |

| content quality | The extent to which the video content is perceived to be of good quality. Responses related to the content rather than technical or source quality are classified under this code. |

| technical quality | The extent to which image and sound are perceived to be of good quality. |

| cinematography | The extent to which the video contained any specific film techniques the participant was interested in. |

| visual appeal | The extent to which the thumbnail was appealing to the participant. |

| sound or voice | The extent to which the participant likes the sound or voice content of the video. |

| cost | The extent to which some cost will be involved to obtain a video. |

| language and subtitles | The extent to which the language that was spoken in the video is understandable by the participant, and if it was in a foreign language, whether there were subtitles shown in the video. |

| version | The extent to which different versions exist and judgements are based on the version of the video. |

| availability | The extent to which a number of videos that cover the same topic are available and judgements are based on this aspect. |

| verification | The extent to which information provided in the video is consistent with or supported by other information or the extent to which the participant agrees with the information presented. |

| unusualness | The extent to which a video provides unique, weird or distinctive information comparing to other videos. |

| rank order | The extent to which participant's decision to select a video is influenced by its position in the ranked list. |

| popularity | The extent to which the video has a large number of views or likes. |

| recommended video | The extent to which a participant's judgement was influenced by recommendations provided by friends, YouTube, web pages or social media sites. |