A cross-discipline comparison of subject guides and resource discovery tools

A.F. Tyson, and Jesse David Dinneen

Introduction. Academic libraries invest considerable resources in creating disciplinary subject guides, but patron use of such guides is rarely quantified in the literature. We analyse access data for subject guides and other electronic resource discovery tools to investigate disciplinary differences in resource discovery behaviour.

Method. We analysed access data for resource discovery tools and subject guides that was collected over five weeks in the first term of the academic year at a public teaching and research university.

Analysis. We analysed unique page views for subject guides, then calculated and compared access to electronic resources originating from the following resource discovery tools: Summon, subject guides, Google Scholar, and the database index.

Results. Disciplines with high unique page views for subject guides were more likely to use subject guides or specific databases for resource discovery, while disciplines with low subject guide unique page views were more likely to use Summon or Google Scholar for resource discovery.

Conclusions. The low unique page views for most guides suggests providing guides for all disciplines may not be an effective method for supporting students in resource discovery. This study also indicates a need for subject guide use to be evaluated in relation to other resource discovery tools.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper871

Introduction

Subject guides, also known as pathfinders or research guides, have been created by academic librarians since the 1950s and are ‘usually annotated bibliographies of reference materials, databases, journals and web sites within a particular discipline’ (Vileno, 2007, p. 434). Originally created as print pamphlets listing resources and their location in the library, subject guides are now usually online resources, with links to online sources, search tools and lists of print resources. LibGuides, a commercial content management system, is the dominant software used in academic libraries to create subject guides. (Accordingly, in this study, subject guide and LibGuides are used interchangeably, reflecting these terms’ use in the literature).

Academic libraries invest staff time and financial resources in making disciplinary subject guides with, thus far, little evidence of much use by their patrons. Recent analyses of subject guide use data discovered that an unexpected proportion of use, in one case as much as 70%, was from users unaffiliated with the library (Castro-Gessner, et al., 2013). Furthermore, students have reported preferring other library tools to subject guides (Conerton and Goldenstein, 2017; Costello, et al., 2015). Subject guides have been redeveloped as online resources in response to the changing expectations of patrons used to navigating a Web 2.0 world, yet the literature does not consider what the rise in a multitude of electronic resource discovery tools might mean for the utility of subject guides. Some studies have found that the development of course-specific or topic guides attract high use (Bowen, 2012; Chiware, 2014; Yeo, 2011), but discipline-specific guides are still the predominant form of subject guides. It is not clear that patrons still need such guides to locate appropriate academic resources when library information resources may often be easily accessed via alternative tools such as Web-scale discovery and Google Scholar. In other words, students may be finding academic resources with Google Scholar in cases where a disciplinary subject guide could have been used, which would arguably bring into question the rationale for investing staff time and resources in creating such guides.

We were interested in investigating the use of subject guides at a public teaching and research university library and contrasting this with the use of the other resource discovery tools on offer. This library had been providing discipline-based subject guides online using Springshare’s LibGuides platform since 2012. Other resource discovery tools on offer include Proquest's Summon service (since 2009) and a database index, with the library’s collections also discoverable and accessible through Google Scholar. This study sought to quantify the use of subject guides in relation to other resource discovery tools at a disciplinary level by answering the following research questions:

RQ1 How many subject guide views in one academic library can be attributed to patron use and does that differ across disciplines?

1a) What proportion of subject guide page views can reasonably be attributed to the library’s patrons?

1b) What are the page view statistics for each subject guide relative to student enrolments in the corresponding discipline?

RQ2 Which resource discovery tools, including subject guides, are used most in one academic library to access electronic resources and does access method differ across disciplines?

2a) What proportion of access to electronic resources originates from each of the following resource discovery tools: subject guides; Summon; Google Scholar; database index?

2b) What are the disciplinary differences (if any) in the proportion of access originating from the considered set of resource discovery tools?

Literature review

The use of subject guides is rarely quantified in the literature beyond vendor-generated use statistics, nor is use often interrogated to identify who is accessing subject guides. Yet several recent studies have found that subject guide use can be attributed as much to an international audience, as that of a library’s patrons (Castro-Gessner, et al., 2013; Campbell, et al., 2016). Furthermore, students report using other resource discovery tools offered by libraries in preference to subject guides (Conerton and Goldenstein, 2017; Costello, et al., 2015). Technological advances and associated changes in information seeking behaviour invite a reconsideration of the role of subject guides within academic libraries’ broader information environment.

A number of studies have drawn on vendor-provided use statistics to quantify subject guide use, but actual use by library patrons often remains ambiguous. For example, a number of studies fail to contextualise use statistics with reference to student numbers, making it difficult to assess whether the guides are well used (Adebonojo, 2010; Courtois, et al., 2005; Dalton and Pan, 2014). One study that did contextualise use in relation to student enrolments uncritically compared Springshare-generated access statistics with Google Analytics data (generated for previous non-LibGuides subject guides) as evidence of increased use (Yeo, 2011). This is of concern because page view statistics provided by Springshare can include bot hits, multiple hits from one IP address, and library staff use, artificially inflating use statistics (Farney, 2016; Griffin and Taylor, 2018). Furthermore, the vendor-provided statistics cannot be parsed to identify who is accessing subject guides. Several studies have employed Web analytics to discover that most use was from users unaffiliated with the library, including a significant stream of international traffic (Campbell, et al., 2016; Castro-Gessner et al., 2013).

The prevailing recommendation in subject guide literature is that better design and greater promotion, whether that be through library instruction, or locating guides in learning management systems, will lead to greater use (Bowen, 2012; Bowen, et al., 2018; Campbell, et al., 2016; Conerton and Goldenstein, 2017; Costello, et al., 2015; Dalton and Pan, 2014; Foster, et al., 2010; Griffin and Taylor, 2018; Mahaffy, 2013; Murphy, 2013; Sonsteby and Dejonghe, 2013; Staley, 2007; Thorngate and Hoden, 2017). However, these suggestions fail to address the fact that library patrons report preferring a range of alternative discovery tools to subject guides (Conerton and Goldenstein, 2017; Costello et al., 2015; Ouellette, 2011). While tempting to assume the patrons were referring to Google or Google Scholar, they in fact preferred alternative discovery tools offered by the library (Conerton and Goldenstein, 2017; Costello et al., 2015) This suggests that rather than ‘consider[ing] user behaviour and observed use patterns’ (Griffin and Taylor, 2018, p. 12) to inform subject guide design, we should be considering subject guide use in relation to the broader suite of discovery tools offered by libraries.

Early iterations of subject guides routinely listed Library of Congress Subject headings and call ranges, relevant reference works, classic works and relevant journal titles (Harrington, 2008). The issue of whether subject guides have evolved to incorporate technological advances in information management has been conceptualised as the extent to which ‘Web 2.0 tools have been integrated within subject guides’ (Morris and Del Bosque, 2010, p. 179). Indeed, links to relevant databases and Websites are the resources most frequently included in Libguide-era subject guides, followed by lists of books in library collections and how-to information (Morris and Del Bosque, 2010). It remains unclear whether subject guides are still necessary, given most academic libraries now offer a suite of Web 2.0 resource discovery tools that have significantly streamlined resource discovery. For example, Web-scale discovery (Foster, 2018), library-linked Google Scholar (Asher, et al., 2013; Dixon, et al., 2010), and resource links in learning management systems (Cross, 2015; Reading list..., 2015), are all examples of such tools that have simplified resource discovery and call into question whether subject guides are still meeting patrons’ resource discovery needs.

Convenience and ease-of-use, found to be primary factors in academic information seeking behaviour, are the underlying features of these Web 2.0 tools (Connaway, et al., 2011; Joo and Choi, 2015). Connaway et al. (2011) report that patrons find ‘wad[ing] through separate lists and groupings of library content and different indexing and abstracting databases’ (p. 187) inconvenient, yet subject guides are usually subject-specific lists of resources and individual databases (Vileno, 2007). The suite of Web-scale discovery tools available in contemporary academic library information ecosystems provide easily accessible information sources, begging the question: do patrons still need a subject guide to locate the resources required?

There is some evidence in the literature that library patrons do not use subject guides to locate resources. A 2013 study surveyed students to evaluate the impact of the recent adoption of a Web-scale discovery tool on use of other tools and services offered, including subject guides (Mussell and Croft, 2013). Just 1.7% of respondents named subject guides as their first port of call when starting research, higher only than Wikipedia, contacting a librarian, and using online tutorials. Alternatives to subject guides, such as Google Scholar, databases, a Web-scale discovery tool and the catalogue, all had higher reported use. When asked to name all the resources they used, 7% of respondents named LibGuides, equal to those who contacted a librarian and higher only than online tutorials. Yet 22% reported using the new Web-scale discovery tool. However, this study did not consider whether use patterns of resource discovery tools, including subject guides, differed across disciplines. There is little mention of academic discipline in the subject guide literature, beyond an aside from Murphy and Black that ‘[s]ome academic disciplines, especially in the sciences, rely on a limited set of discovery tools, making the need for a customized library guide less pronounced’ (2013, p. 533). Yet recent quantitative analyses of library use have found disciplinary differences in the use of digital resources (Jara et al., 2017; Kim, 2011; Nackerud, et al., 2013), suggesting that use of subject guides could differ across disciplines. Whilst studies have reported individual guide use, a cross-disciplinary analysis was not found in the literature.

In summation, literature that investigates subject guide use either relies on vendor-generated use data, or fails to contextualise use statistics with reference to enrolments or academic discipline. As a result, student usage of subject guides has not been adequately quantified. The rise in one-search box resource discovery tools in academic libraries meets a growing expectation of convenient google-like search interfaces, and may also be supplanting the need for subject guides. Therefore, there is a need to contextualise subject guide use statistics within the broader academic library information environment to identify the value of subject guides to patrons.

Methods

This research project focussed on the use of subject guides and resource discovery tools offered by the library at the University of Canterbury, a public teaching and research university in Christchurch, New Zealand. In 2019 there were 18,364 enrolled students, with 14,891 students enrolled in a full-time course of study (University of Canterbury, 2020). Access data for subject guides and electronic resources was gathered over five weeks in the first term of the 2019 academic year.

Given the issues with relying on Springshare-generated data identified in the literature review, Google Analytics was chosen as a tool to gather subject guide access data. This tool enables bot hits and specific source IP ranges to be excluded from data collection, and enables data to be sorted by the source geographic location of hits. This would enable the data to be restricted to that likely to be associated with UC library patrons (i.e. students and staff). In addition, Google Analytics provides unique page view statistics, aggregating multiple page views from a user within one session, preventing the data from being artificially inflated with multiple hits from individual users (Google, n.d.).

The configuration of the library Website precluded using Google Analytics to quantify resource discovery tool use (Google Analytics require an individual page for each resource being tracked, and some Web pages provided access to multiple resources). The library uses an EZproxy server to mediate access to all electronic resources, with all access data recorded in server logs. A number of studies have used EZproxy data to study electronic resource usage (Brown and Smith, 2017; Jara et al., 2017; Nackerud et al., 2013; Samson, 2014; Yeager, 2017), therefore EZproxy data was selected to investigate resource discovery tool use.

| Research stage | Research question | |

|---|---|---|

| RQ1. How many subject guide views can be attributed to patron use and does that differ across disciplines? | RQ2. Which resource discovery tools, including subject guides, are used most to access electronic resources and does access method differ across disciplines? | |

| Data set and source | ● record of all unique page views for all relevant subject guide pages for 4 March – 7 April 2019 ● data from Google Analytics | ● record of all hits on electronic resources provided by the Library for 4 March – 7 April 2019 ● data from EZproxy server |

| Data collection | Before collection: ● Exclude library staff IP address ranges and international access After collection ● Extract data set detailing unique page views per page from Google Analytics. ● Request data from institution regarding enrolment numbers per subject. [Consider using numbered bullet points, as below, for consistency] | Data downloaded from the EZproxy server and saved in a plain text file. Each line of data records which user accesses what file and at what time. |

| Data preparation | 1. Sort page view data by subject guide, and then sort guide data into disciplinary groups 2. Sort enrolment numbers per course as provided by institution into enrolment numbers per discipline. | 1. Data set refined to relevant data using python script (See Angelo (2019) for complete details). 2. Refine dataset to include only lines of codes with hits to the 12 sample databases. 3. Remove lines of code with a 300 HTTP status code and subject guide, Google Scholar or database index Prior URL field. 4. Manually review lines of code with a 300 HTTP status code and Summon Prior URL field to delete duplicate lines. |

| Data analysis | Calculate total page views for each disciplinary group of subject guides compared to the proportion of students enrolled in that discipline. Identify most and least accessed guides relative to student numbers for the related discipline. | Calculate the proportion of access to sample electronic resources that originates from, ● each resource discovery tool. ● each resource discovery tool as a proportion of all use for each sample database. |

Data preparation

Google analytics data

Google Analytics data can be filtered to exclude specific sources of page views. Multiple filters to exclude UC library staff IP address ranges and access originating outside of New Zealand were applied within the Google Analytics platform before data collection. The sizeable distance student cohort at UC precludes refining the geographic filters further, with the institution currently having only a handful of international distance students. It is assumed that these filters effectively limited the data to that likely from UC library patrons (i.e., UC students and staff).

The view data for each page on the subject guides were sorted into 63 groups, one for each subject guide listed on the library homepage, as indicated by the title of the page. Because a number of the guides were for specific subjects taught at this institution, that did not necessarily constitute separate disciplines (e.g., there were 11 subject guides for different branches of engineering), these guides were sorted into one of 22 possible academic disciplines using The Australian and New Zealand Standard Research Classification (ANZSRC) (Pink and Bascand, 2008).

Close analysis of the data revealed the presence of course-specific pages in some guides. As previous studies have found that course guides attract higher views than disciplinary guides (Bowen, 2012; Chiware, 2014; Yeo, 2011), and disciplinary guides were our object of study (rather than course-specific ones), data about unique page views to eight course-specific pages were excluded (see Appendix C).

EZproxy data

One of the challenges of using EZproxy server logs is the sheer volume of data created: the five weeks of data collected for this project constituted approximately 5 million lines of code. This is because the logs record all HTTP transactions between the server and client, including transfer of images, scripts and other material. Since we were only interested in which resources tools were being used to begin a search for information, the data was compiled, formatted and refined using a python script to capture only patrons’ first entrance into a database (See Angelo (2019) for script).

After this refinement, the dataset contained 1,430,344 lines. The size of the dataset, combined with the sheer number of databases (346) offered by the library, precluded a complete analysis, so a sample of twelve databases is analysed. Two core databases for three of the most highly used subject guides and three of the least frequently used subject guides (according to the analysis of subject guide use detailed above) are analysed. Lines of code containing a request for the twelve sample databases were identified by the domain, host, path or query field within the Request URL, with each database’s data saved in a separate Excel file. A complicating factor in identifying database data was the inclusion in the database sample of databases accessible via aggregator platforms (e.g. EBSCOhost). These databases cannot be identified by the URL domain alone (Brown and Smith, 2017). For these three databases, relevant lines of code were identified by the URL domain (indicating the platform) in conjunction with the relevant database codes appearing in the URL Path (ProQuest) or URL Query (EBSCOhost).

Another consideration in preparing the data was the potential for high users of electronic resources to skew the results. Analysis of the frequency of IP addresses revealed that there was indeed a wide range in frequency, with some IP addresses recurring at rates of up to 100 times the average. For this reason, once the data was refined down to lines of codes for each of the sample disciplines, confidence intervals were calculated for IP address frequency in the dataset to identify unusually high users of electronic resources. IP addresses that occurred in the dataset at a frequency either less than the lower bound value or higher than the upper bound value (these differed for each discipline) were removed from the data set to ensure that the picture of resource discovery generated from the data reflected typical patron behaviour. Further detail regarding the identification and cleaning of the EZproxy data is available online (Tyson, 2019).

Data analysis

Analysis of LibGuides use

Descriptive statistics were employed to calculate:

- unique page views for each disciplinary group of subject guides as a proportion of total page views

- unique page views for each disciplinary group of subject guides relative to student enrolments in the related discipline.

It was hypothesised that there would be significant differences in the unique page view figures for particular subject guides, with a handful of highly used guides and most guides having low use. This would suggest disciplinary differences in information seeking behaviour may be a factor in subject guide use. Alternatively, a number of guides having high use would suggest library patrons find subject guides to be relevant resource discovery tools; while generally low use for guides would suggest library patrons are using alternative resource discovery tools.

Analysis of access data for electronic resources.

Descriptive statistics were employed to calculate

- the proportion of access to all electronic resources that originates from each resource discovery tool.

- the proportion of access to each individual database that originates from each resource discovery tool.

It was hypothesised that for databases associated with low-use subject guides, the most common referrer would be Summon or Google Scholar because students do not require subject-specific tools to find the information resources they require and these tools are more convenient. Conversely, for databases associated with high-use subject guides, it was hypothesised the most common referrer would be subject guides or the database index because general resource discovery tool searches do not locate the required resources. If this is the case, then this indicates there may be disciplinary differences in how students access resources. If this is not the case, then this means factors other than academic discipline influence how students access resources.

Results

Subject guide access

Analysing the Google Analytics access statistics for subject guides revealed that 68.2% (24,680 of 36,166) of unique page views were likely from library patrons, as detailed in Table 2. Approximately 31.7% (11,486 of 30,888) of total use did not originate from library patrons.

| Total views | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| New Zealand (excluding library staff) | 24,680 | 68.2% |

| International | 8,979 | 24.8% |

| Library staff | 2,507 | 6.9% |

| Total | 36,166 | 100% |

Further analysis of the data focussed on the 24,680 views originating from within New Zealand, but not from library staff. Four disciplinary groups of subject guides attracted 82% (20,279 of 24,680) of all page views. Most disciplinary groups of guides had lower unique views, as detailed in Table 3, whilst law and legal studies, and engineering, had the highest use.

| Total unique views (per discipline) | ANZSRC discipline (Pink and Bascand, 2008). | Total equivalent full-time student enrolments in Semester 1, 2019 |

|---|---|---|

| 9470 | Law and legal studies | 663.6 |

| 2012 | Studies in human society | 538.3 |

| 1938 | Education | 784 |

| 1657 | Engineering | 1209.5 |

| 907 | Language, communication and culture | 444.5 |

| 765 | Medical and health sciences | 382.7 |

| 585 | Economics | 1089.3 |

| 368 | History and archaeology | 87.5 |

| 283 | Psychology and cognitive sciences | 434.8 |

| 258 | Earth sciences | 214 |

| 203 | Biological sciences | 259.2 |

| 100-200 | Philosophy and religious studies; Māori studies; Chemical sciences; Studies in creative arts and writing | 80.1 115.3 144.9 156.4 |

| Fewer than 100 | Pacific people studies; Environmental sciences; Agricultural and veterinary sciences; Technology; Physical sciences Information and computing sciences; Mathematical sciences |

5 54.3 61.2 90.5 203.4 345.8 600.7 |

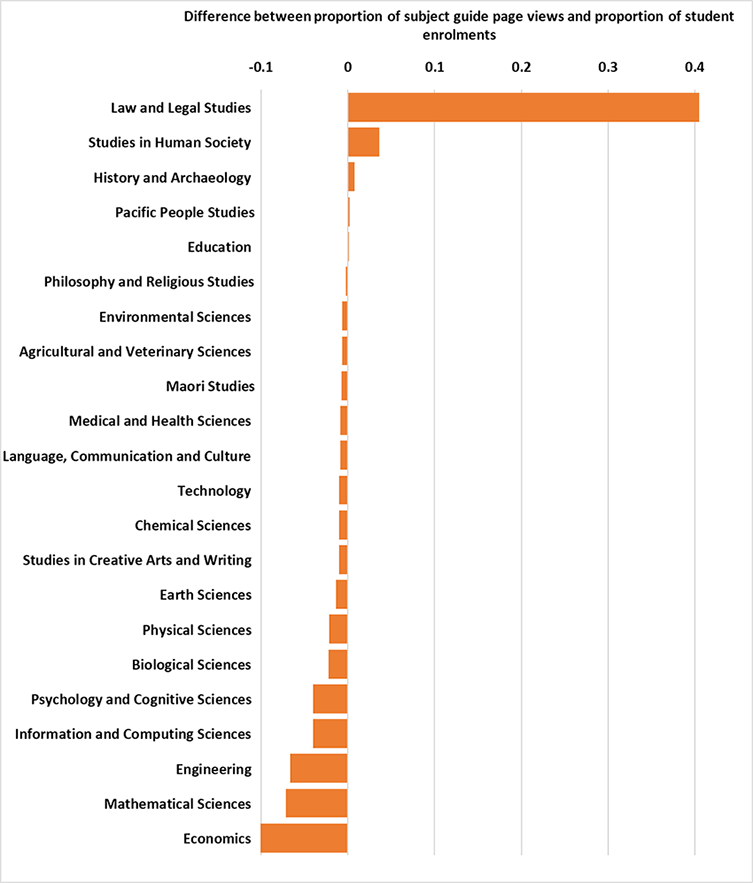

When considered as a proportion of all subject guide views, as depicted in Figure 1, law and legal studies had an almost five times greater proportion of views than of student enrolments; the proportion in studies in human society was slightly higher than the proportion of enrolments; and it was approximately equal in education. For the small field of history and archaeology (in terms of student enrolment) the proportion of subject guide views was almost double and in the remaining disciplines the proportion of subject guide views was smaller than the proportion of student enrolments. Disciplinary groups with a disproportionately high use have a positive score on the Y-axis while those with disproportionately low use have a negative score on the X-axis of Figure 1.

Figure 1: Difference between proportions of subject guide page views and student enrolments

While law and legal studies, history and archaeology and studies in human society had disproportionately high use, economics, mathematical sciences, and engineering had disproportionately low use. These six disciplines were selected as a sample to investigate differences between high and low subject guide use disciplines in the use of the resource discovery tools Summon, subject guides, Google Scholar and the database index.

Resource discovery tool access.

Databases were selected using the core databases listed on the sample subject guides (with multidisciplinary databases such as Scopus or JSTOR excluded from selection), as detailed in Table 4.

| Use level | Discipline | Databases |

|---|---|---|

| High use guides | Law and legal studies | Westlaw NZ Hein Online |

| History and archaeology | Historical Abstracts Cambridge Histories | |

| Studies in human society | Sociological Abstracts Political Science Complete | |

| Low use guides | Economics | Business Source Complete OECD iLibrary |

| Engineering | IEEE Compendex | |

| Mathematical sciences | MathSciNet ACM Digital Library |

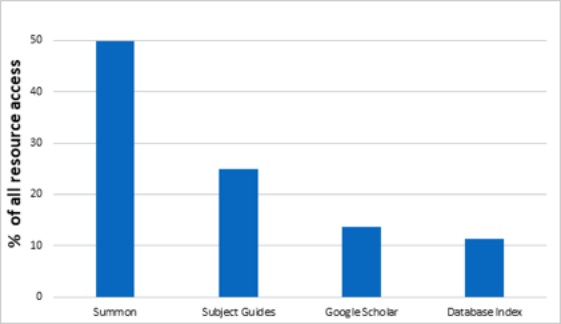

Data for the twelve sample databases were analysed to identify the proportion of access to electronic resources that originated from each of the four following resource discovery tools: subject guides; Summon; Google Scholar; and the database index. Figure 3 shows that Summon was used for roughly half of the access to electronic resources, with subject guides used almost one-quarter of the time. The database index and Google Scholar were the least used resource discovery tools.

Figure 2: Proportion of library patron access to electronic resources through the four main resource discovery tools.

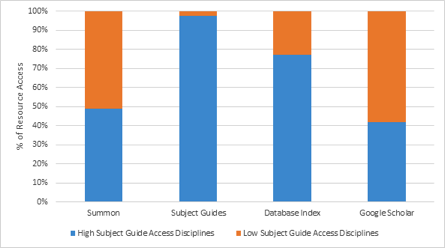

However, as shown in Figure 4, the use of these discovery tools varies between high and low subject guide access disciplines. High subject guide use disciplines account for the majority of access via subject guides and the database index, while the use of Summon and Google Scholar is more evenly spread, regardless of discipline.

Figure 3: Comparison of resource discovery tool use between high and low subject guide access disciplines

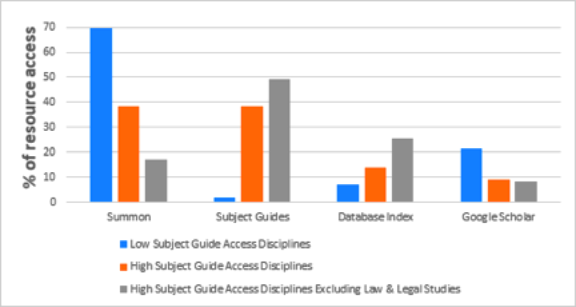

For databases associated with low-use subject guides (economics, engineering and mathematical sciences), the most common referrer is Summon. Conversely, for databases associated with high-use subjects (law and legal studies, studies in human society, and history and archaeology), subject guides and Summon are the most common referrers. High subject guides access disciplines used subject guides and the database index more frequently, while low subject guide access disciplines used Summon and Google Scholar more frequently. However, the law and legal studies data dominates the high subject guide use disciplines, with Summon just outpacing subject guides to be the most common referrer to the sample law databases. When law and legal studies is excluded from high subject guide access disciplines, subject guides and database index are the most frequently used resource discovery tool (See Figure 5).

Figure 4: Discovery tool use in relation to subject guide use

To identify whether, as hypothesised, the most common referrer for databases associated with low-use subject guides was Summon or Google Scholar, while the most common referrer for databases associated with high-use subject guides was subject guides or the database index, the results were organised into a 2 x 2 contingency table (see Table 5).

| Access level | Subject-specific discovery tools (i.e., subject guides/ database index) | Multidisciplinary discovery tools (i.e., Summon/Google Scholar) | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|

| High subject guide access disciplines | 856 | 776 | 1632 |

| Low subject guide access disciplines | 83 | 867 | 950 |

| Totals | 939 | 1643 | 2582 |

The discrepancy in the use of subject-specific discovery tools to access resources from databases associated with high versus low subject guide access disciplines shows a contingency between disciplinary subject guide access and subject-specific discovery tool usage. However, there is not the same discrepancy in the use of multidisciplinary discovery tools, indicating that disciplinary subject guide use is independent of multidisciplinary tool access.

A chi-squared test of independence was performed to examine the relationship between discovery tool and subject guide access, with the result, X2 (1, N = 2582) = 495.839, p = < 0.00001, which is significant at p < 0.05. This confirms a strong relationship between discovery tool and subject guide access, and that this study’s findings are unlikely to be due to chance. It can therefore be inferred that the choice of resource discovery tool to access a disciplinary database is not independent from subject guide access for that discipline. Calculating odds ratios for these relationships further explicates the association between the variables (Agresti, 2013), as shown in Table 6. There is a strong association between low subject guide access and the access of multidisciplinary discovery tools.

| Access level | Subject-specific discovery tools (i.e., subject guides/ database index) | Multidisciplinary discovery tools (i.e., Summon/Google Scholar) |

|---|---|---|

| High subject guide access disciplines | 1.103092784 | 0.906542056 |

| Low subject guide access disciplines | 0.095732411 | 10.44578313 |

While high subject guide use is positively associated with accessing resources via subject guide or the database index (1.10), this association is not strong, nor is the negative association with the use of Summon or Google Scholar particularly strong. Yet, low subject guide use is very positively associated with accessing resources via Summon or Google Scholar (10.4), and very negatively associated with the use of subject guides and the database index (0.09) (Values of less than 1.0 indicate a negative relationship).

Given the high use of subject guides as a discovery tool by high subject guide access disciplines in the descriptive analysis, the low odds ratio for this association was surprising. Assuming that the high use of Summon as a discovery tool for accessing law and legal studies databases was responsible for the low odds ratio, the odds ratios were recalculated excluding law and legal studies data to identify whether there was a stronger association for the other two high subject guide access disciplines (see Table 7). There is a strong association between high subject guide access disciplines and the access of subject-specific discovery tools.

| Access level | Subject-specific discovery tools (i.e., subject guides/ database index) | Multidisciplinary discovery tools (i.e., Summon/Google Scholar) |

|---|---|---|

| High subject guide access disciplines | 2.981818182 | 0.335365854 |

| Low subject guide access disciplines | 0.095732411 | 10.44578313 |

The odds ratio of 2.98 demonstrates a much stronger association between high disciplinary subject guide use and use of subject-specific discovery tools to access resources for studies in human society and history and archaeology.

Discussion

Subject guide access

Answering Research Question 1(a), 'What proportion of subject guide page views can reasonably be attributed to the library’s patrons?'' this study found that 62.8% subject guides can be attributed to library patrons. An earlier study at Cornell University found up to 70% of access was from users unaffiliated with the library (Castro-Gessner, et al., 2013), but this study is more in line with that at the University of South Florida (Griffin and Taylor 2018), which also found most users were likely to be library patrons. Nonetheless, over a third of all subject guide page views are not from library patrons. This figure, in and of itself, is not necessarily alarming, if subject guides are generally being frequently accessed, since such access could be considered good marketing for the institution and also an example of information as a public good. However, while the guide for law and legal studies had notably high unique page views (9740), all other disciplinary guides had much lower total unique page views with only three other guides exceeding 1000 unique page views. Raw counts are difficult to interpret, as there is no established standard by which to judge what constitutes high or low access. While some studies have detailed page views with raw counts (Yeo 2011; Castro-Gessner, et al., 2013; Griffin and Taylor 2018), the different number of guides, number of students, and periods of data collection in each study complicates drawing meaningful comparisons. Given the depth of literature on subject guides, such a meta-analysis would be a valuable future research project to enable libraries to evaluate the performance of their subject guides.

The data gathered to answer Research Question 1(b), 'What are the page view statistics for each subject guide relative to student enrolments in that subject?' underlines the importance of contextualising raw hits with reference to student enrolments. Comparing each guide’s proportion of all subject views, relative to enrolment numbers, revealed disciplinary guides for law and legal studies, studies in human society, history and archaeology, Pacific people studies and education disciplines all achieved a greater share of hits than their share of student enrolments. Nonetheless, most guides had low unique page views, with those for the law subject guide far exceeding other guides and studies in human society and history and archaeology lagging far behind as the second and third most viewed guides. This distribution replicated the finding by Castro-Gessner, et al. (2013) that approximately seven percent of guides at Cornell University attracted the bulk of subject guide traffic.

The range of factors that influence subject guide use cannot be disregarded, including the role of instruction and the location of guides on the Website. It is important to acknowledge that the law subject guide is heavily promoted in compulsory workshops that are embedded within the law programme. At the university where the study took place, other disciplines are not yet embedded within programme curricula, with the result that the subject guides are not as heavily positioned as a necessary tool for information discovery. But there is conflicting evidence as to the importance of instruction in influencing student selection of discovery tools, with Kim (2011) finding it was an important factor, while Joo and Choi (2015) found it was not. Such inconsistency is evident in this study, with subject guides for studies in human society, history and archaeology, Pacific people studies and education disciplines attracting a greater share of page views than expected from enrolments, despite not being promoted via embedded curriculum content. It seems likely that some specificity about information discovery for these disciplines (and law) attracts patrons to these guides, suggesting they find them to be relevant resource discovery tools.

In summary, to answer Research Question 1, 'How many page views of subject guides can be attributed to patron use and do page view figures differ across disciplines?' this study has found that almost two-thirds of page views can be attributed to patron use and that three disciplinary groups of guides attracted the bulk of page views. The low unique page views for most subject guides suggests students in these disciplines may be using alternative resource discovery tools.

Resource discovery tool access

Answering Research Question 2(a), 'What proportion of access to electronic resources originates from each of the following resource discovery tools: subject guides; Summon; Google Scholar; database index?', this study found that Summon, the Web-scale discovery tool, was the most commonly used resource discovery tool by Library patrons, with just short of 50% of all searches starting in Summon. This matches earlier studies that found Web-scale discovery tools quickly surpassed individual databases in usage for finding articles (Way, 2010; Mussell and Croft, 2013). Perhaps unexpectedly, given the data for subject guide use, just under 25% of searches started with subject guides, with the remaining access originating from database index and Google Scholar.

Understanding resource discovery tool access is complicated by the findings for Research Question 2(b), 'What are the disciplinary differences (if any) in the proportion of access originating from the considered set of resource discovery tools?' This study found distinct disciplinary differences in the use of the four resource discovery tools. Disciplinary differences in library use have been found in previous studies (Kim, 2011; Beasley, 2016; Jara et al., 2017), but this study is the first to compare the use of discovery tools by discipline. The disciplinary differences found is perhaps most starkly illustrated by the figures for the use of multidisciplinary resource discovery tools. For the disciplines with high subject guide use, 15-50% of all searches started in Summon or Google Scholar. In comparison, for disciplines with low subject guide use, 85-95% of all searches started in Summon or Google Scholar.

Given studies demonstrating patron preference for the Google Scholar interface (Wilkes and Gurney, 2009; Wells, 2016; Greenberg and Bar-Ilan, 2017), it was expected that Google Scholar would be used for resource discovery more frequently than demonstrated in this study. Even in disciplines heavily reliant on Summon, such as engineering and mathematical sciences, which would plausibly lead to the use of another one-search box tool, such as Google Scholar, use was comparatively low. The only exception was economics, where Google Scholar accounted for over one third of all searches. The inclusion of marketing in the economics discipline and the particular information needs of this subject (such as consumer and corporation information) may account for the higher use of Google Scholar, a conclusion supported by previous research which found business students were more likely to use commercial Websites than library resource discovery tools (Kim, 2011).

As expected from the subject guide access figures for law and legal studies, subject guides were heavily used to access the law databases. Given the subject guide is positioned as the starting point for research in embedded tutorials, it is notable that Summon was used slightly more. Students in law are often enrolled in other disciplinary courses, raising the possibility that the dominance of Summon as a resource discovery tool in other disciplines leads to its use in spite of instruction. This suggests that the principle of least effort informs resource discovery tool selection, with a focus on convenience and ease of use (Thomsett-Scott and Reese, 2012; Joo and Choi, 2015). The possibility that students try Summon, before returning to the subject guide to find resources, must be acknowledged, although the inclusion of only 2-300 HTTP status codes in this study suggests that Summon is providing access to resources. This raises the possibility that Summon will gain further dominance in this discipline as a resource discovery method, especially as Web-scale functionality continues to evolve.

Studies in human society also had particularly high resource discovery referrals from subject guides, with over half of searches starting in the subject guides. Criminal justice is included in this discipline, and is a subject closely allied with law, raising the possibility that curriculum-embedded promotion by the same subject librarian, akin to that for law, has led to the dominance of the subject guide as a research starting point. However, the databases Political Science Complete (mainly used in political science, the guide for which attracted access comparable to that for criminal justice) and Sociological Abstracts (used for almost all of the subjects in this discipline) were the two sample databases. So, the suggestion that the subject guides for the studies in human society discipline offer content that assists resource discovery better than other discovery tools must also be considered (Kim, 2011). The disciplinary differences found in the data support this study’s contention that disciplinary factors inform subject guide access statistics.

Interestingly, history and archaeology was the one discipline for which the database index was the most common access point to electronic resources. Depending on whether a patron accessed the alphabetical list of databases (the most common referrer from the database index) or the disciplinary list of databases (also available on the same Web page of the library Website), access to the databases requires 2-3 clicks to access a specific database. In terms of effort required to access this discovery tool, it requires more effort than Summon, but less than a subject guide. It also requires knowledge of the specific database required. This raises the question of whether the sample population captured in this study was different to that of the other disciplines. Perhaps the access behaviour of postgraduate researchers and academics, more than undergraduate students, has been captured, a possibility strengthened by the reliance of this discipline on monographs as much as serials in undergraduate study. Nonetheless, the dominance of subject guides and the database index for this discipline indicates the strong disciplinary differences in resource discovery tool access.

In summary, to answer Research Question 2, 'Which resource discovery tools, including subject guides, are used most to access electronic resources and does access method differ across disciplines?', Summon and subject guides were the resource discovery tools used most to access electronic resources, but there were substantial differences between disciplines.

The role of subject guides in resource discovery

Limitations

This analysis of subject guide and resource discovery access rests on a number of assumptions. The first is that patrons in all disciplines are required to independently find resources to complete their coursework. Use of each individual resource discovery tool was calculated as a proportion of each discipline’s total resource discovery searches to enable comparison between disciplines. Interestingly, calculating each sample discipline’s share of total searches reveals each discipline’s share was roughly commensurate with its share of total enrolments, except law which conducted twelve times its share of searches than might be expected from enrolments. The use of course enrolment level data also precluded an analysis of disciplinary usage that considered differences in resource discovery between non-majors and major students in each discipline, a factor that could be considered in future studies.

Another assumption is that resource discovery statistics for the six sample disciplines are representative of that discipline’s resource discovery. The two databases chosen for each sample discipline were chosen because they were discoverable by each of the four methods being measured (subject guides, database index, MultiSearch and Google Scholar) and because they were distinctly disciplinary. A large number of disciplines also rely on multidisciplinary databases but because of the difficulty of distinguishing the discipline of the patron, these were not considered for the sample. A future study that links a user’s identity to a particular discipline would allow a more comprehensive sample of databases, although this may be difficult for users in multidisciplinary fields or enrolled in multiple disciplines.

A potential limitation lies in the subject guide data. Although this study excludes library staff and international access to subject guides, the remaining access could be by any individual within New Zealand and therefore include some access by users unaffiliated with the library. Nevertheless, the sizable distance student cohort at this institution precluded refining the geographical location of users any further. However, there is no reason to think that unaffiliated users would access any particular subject guide more than another. Given this, along with the fact that use is analysed in terms of proportions rather than absolute figures, it is assumed any unaffiliated use does not significantly influence the results.

Finally, the main limitation of this study is the limited insight into use afforded by access statistics. Page view counts only tell us students accessed a subject guide page, not whether they found the page useful. Nonetheless, when page views differ greatly between guides, we can reasonably assume that some students find guides useful and some do not. However, we cannot assume the reasons they do, or do not, find guides useful without conducting further research with users to gain insight into their behaviour. Similarly, resource discovery searches only reveal how students started a search, not why they started a search in the way they did and whether it was successful. Again, when discovery methods differ markedly between disciplines, we can reasonably assume that discipline plays a role in choice of resource discovery tool but further research is required to delve into this further.

Conclusion

Understanding which resource discovery tools and services patrons are using is essential for meeting patrons’ information needs and the wise management of library resources. Subject guides are an established tool offered by academic libraries to help patrons find resources, but there is little data confirming significant use by patrons. This study found low unique page views for subject guides, with the exception of three disciplines. Disciplinary differences were found in the use of information resource discovery tools to access electronic resources. Disciplines that had high access rates for subject guides were more likely to commence information resource searches in subject guides, or a specific database, while disciplines with low access rates for subject guides were more likely to commence information resource searches in Summon or Google Scholar

Much has been written about subject guides and how to boost their use. The findings of this study suggest that subject guide use cannot be meaningfully evaluated in isolation from the broader information discovery context. That is, academic discipline and the other resource discovery tools offered by the library have a bearing on the use of subject guides. Given the low use found for most subject guides and the dominance of Summon, in particular, as a resource discovery tool, the creation of subject guides for some disciplines may not be a worthwhile method for supporting patrons in resource discovery. Longitudinal studies of resource discovery tool use, while controlling for the influence of factors such as promotion, would enable greater insight into the drivers of resource discovery tool selection. Further research into disciplinary differences in resource discovery is required, but offers a rich opportunity to develop and promote resource discovery tools according to patron need.

Acknowledgements

This study would not have been possible without the much-appreciated assistance of Anton Angelo, who generously wrote the Python script to parse and process the EZproxy server logs into .csv files that could be analysed.

About the authors

A.F. Tyson is a subject librarian at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand. She received an M.A degree in English (2007) from the University of Canterbury and a Master of Information Studies from Victoria University of Wellington (2020). She can be contacted at fiona.tyson@canterbury.ac.nz

Jesse David Dinneen is a Junior Professor in the Berlin School of Library and Information Science at Humboldt University, and was previously Senior Lecturer in the School of Information Management at Victoria University of Wellington (New Zealand). He can be contacted at jdinneen@gmail.com

References

Note: A link from the title is to an open access document. A link from the DOI is to the publisher's page for the document.

- Adebonojo, L. G. (2010). Libguides: Customizing subject guides for individual courses. College and Undergraduate Libraries, 17(4), 398-412. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2010.525426

- Agresti, A. (2013). Categorical data analysis (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Angelo, A. (2019). python script for parsing EZproxy logs. GitHub. https://github.com/antonangelo/ezproxy

- Asher, A. D., Duke, L. M., & Wilson, S. (2013). Paths of discovery: comparing the search effectiveness of EBSCO discovery service, summon, google scholar, and conventional library resources. College and Research Libraries, 74(5), 464-488. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl-374

- Beasley, R. (2016). An exploration of disciplinary differences in the use of Talis at the University of Auckland. [Unpublished Master's research project]. Victoria University of Wellington. http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/handle/10063/5629

- Bowen, A. (2012). A LibGuides presence in a Blackboard environment. Reference Services Review, 40(3), 449-468. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907321211254698

- Bowen, A., Ellis, J., & Chaparro, B. (2018). Long nav or short nav?: Student responses to two different navigational designs using LibGuides Version 2. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 44(3), 391-403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2018.03.002

- Brown, J. M., & Smith, G. M. (2017). Prologue to perfectly parsing proxy patterns. Paper presented at Charleston Library Conference, Charleston, South Carolina. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1973&context=charleston (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3b6gocm)

- Campbell, L., Varnum, K., & Bertram, A. (2016). Enhancing Libguides’ usability and discoverability within a complex library presence. In R. L. Sittler and A. W. Dobbs (Eds.). Innovative LibGuides applications: real world examples (pp. 29-37). Rowman and Littlefield.

- Case, D. O., Given, L. M., & Mai, J.-E. (2016). Looking for information: a survey of research on information seeking, needs, and behavior. Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Castro-Gessner, G., Wilcox, W., & Chandler, A. (2013). Hidden patterns of LibGuides usage: another facet of usability. In Proceedings of the Association of College and Research Libraries Conference, April 10-13, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA (pp. 253-261). American Library Association. https://bit.ly/31THQWP (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3211b8C)

- Chiware, M. (2014). The efficacy of course-specific library guides to support essay writing at the University of Cape Town. South African Journal of Libraries and Information Science, 80(2), 27-35. https://doi.org/10.7553/80-2-1522

- Conerton, K., & Goldenstein, C. (2017). Making Libguides work: student interviews and usability tests. Internet Reference Services Quarterly, 22(1), 43-54. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875301.2017.1290002

- Connaway, L. S., Dickey, T. J., & Radford, M. L. (2011). "If it is too inconvenient I'm not going after it:" convenience as a critical factor in information-seeking behaviors. Library and Information Science Research, 33(3), 179-190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2010.12.002

- Costello, K. A., Del Bosque, D., Skarl, S., & Yunkin, M. (2015). Libguides best practices: how usability testing showed us what students really want from subject guides. In F. Baudino & C. Johnson, (Eds.). 15th Annual Brick and Click: An Academic Library Conference, Maryville, Missouri, November 6, 2015. (pp. 52-60). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED561244.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2XZXJcY)

- Courtois, M. P., Higgins, M. E., & Kapur, A. (2005). Was this guide helpful? Users' perceptions of subject guides. Reference Services Review, 33(2), 188-196. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320510597381

- Cross, R. (2015). Implementing a resource list management system in an academic library. The Electronic Library, 33(2), 210-223. https://doi.org/10.1108/EL-05-2013-0088

- Dalton, M., & Pan, R. (2014). Snakes or ladders? Evaluating a LibGuides pilot at UCD Library. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 40(5), 515-520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.05.006

- Dixon, L., Duncan, C., Fagan, J. C., Mandernach, M., & Warlick, S. E. (2010). Finding articles and journals via Google Scholar, journal portals, and link resolvers: usability study results. Reference and User Services Quarterly, 50(2), 170-181. https://doi.org/10.5860/rusq.50n2.170.

- Farney, T. (2016). Optimizing Google Analytics for LibGuides. Library Technology Reports, 52(7), 26-30. https://journals.ala.org/index.php/ltr/article/view/6129/7910 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/31YH0Ip)

- Foster, M., Wilson, H., Allensworth, N., & Sands, D. T. (2010). Marketing research guides: an online experiment with LibGuides. Journal of Library Administration, 50(5-6), 602-616. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2010.488922

- Foster, A. K. (2018). Determining librarian research preferences: a comparison survey of web-scale discovery systems and subject databases. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 44(3), 330-336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2018.04.001

- Google. (n.d.). The different between Google ads clicks, and sessions, users, entrances, pageviews, and unique pageviews in analytics. Google LLC. https://support.google.com/analytics/answer/1257084?hl=en (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3kPgzNB).

- Greenberg, R., & Bar-Ilan, J. (2017). Library metrics: studying academic users’ information retrieval behavior: a case study of an Israeli university library. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 49(4), 454-467. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000616640031

- Griffin, M., & Taylor, T. I. (2018). Employing analytics to guide a data-driven review of LibGuides. Journal of Web Librarianship, 12(3), 147-159. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2018.1487191

- Harrington, S. (2008). 'Library as laboratory': online pathfinders and the humanities graduate student. Public Services Quarterly, 3(3-4), 37-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228950802110445

- Jara, M., Clasing, P., González, C., Montenegro, M., Kelly, N., Alarcón, R., Sandoval, A., & Saurina, E. (2017). Patterns of library use by undergraduate students in a Chilean university. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 17(3), 595-615. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2017.0036

- Joo, S., & Choi, N. (2015). Factors affecting undergraduates’ selection of online library resources in academic tasks: usefulness, ease-of-use, resource quality, and individual differences. Library Hi Tech, 33(2), 272-291. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHT-01-2015-0008

- Kim, Y.-M. (2011). Why should I use university library website resources? Discipline differences. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 37(1), 9-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2010.10.002

- Mahaffy, M. (2013). Student use of library research guides following library instruction. Communications in Information Literacy, 6(2), 202-213. 10.15760/comminfolit.2013.6.2.129

- Morris, S. E., & Del Bosque, D. (2010). Forgotten resources: subject guides in the era of Web 2.0. Technical Services Quarterly, 27(2), 178-193. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317130903547592

- Murphy, S. A., & Black, E. L. (2013). Embedding guides where students learn: do design choices and librarian behavior make a difference? The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 39(6), 528-534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2013.06.007

- Mussell, J., & Croft, R. (2013). Discovery layers and the distance student: online search habits of students. Journal of Library and Information Services in Distance Learning, 7(1/2), 18-39. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2012.705561

- Nackerud, S., Fransen, J., Peterson, K., & Mastel, K. (2013). Analyzing demographics: assessing library use across the institution. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 13(2), 131-145. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2013.0017

- Ouellette, D. (2011). Subject guides in academic libraries: a user-centred study of uses and perceptions. The Canadian Journal of Information and Library Science, 35(4), 436-451. https://doi.org/10.1353/ils.2011.0024

- Pink, B., & Bascand, G. (2008). Australian and New Zealand standard research classification (ANZSRC). Australian Bureau of Statistics and Statistics New Zealand. https://bit.ly/3h3tnOq (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3azOVQg

- Reading list product category grows. (2015). Smart Libraries Newsletter, 353), 5-6. https://librarytechnology.org/document/20600 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3g1JNFF).

- Samson, S. (2014). Usage of e-resources: virtual value of demographics. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 40(6), 620-625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.10.005

- Sonsteby, A., & DeJonghe, J. (2013). Usability testing, user-centered design, and LibGuides subject guides: a case study. Journal of Web Librarianship, 7(1), 83-94. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2013.747366

- Staley, S. M. (2007). Academic subject guides: a case study of use at San José State University. College and Research Libraries, 62(2), 119-13. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.68.2.119

- Thomsett-Scott, B., & Reese, P. E. (2012). Academic libraries and discovery tools: a survey of the literature. College and Undergraduate Libraries, 19(2-4), 123-143. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2012.697009

- Thorngate, S., & Hoden, A. (2017). Exploratory usability testing of user interface options in LibGuides 2. College and Research Libraries, 78(6), 844-861. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.78.6.844

- Tyson, A. F. (2019). Subject guides and resource discovery [Unpublished master’s research report]. Victoria University of Wellington. http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/handle/10063/8923

- Vecchione, A., Brown, D., Allen, E., & Baschnagel, A. (2016). Tracking user behavior with Google Analytics events on an academic library web site. Journal of Web Librarianship, 10(3), 161-175. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2016.1175330

- University of Canterbury. (2020). Annual Report-Te Pūrongo ā-Tau 2019. https://www.canterbury.ac.nz/media/documents/annual-reports/1-Annual-Report-2019-Full.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2Y7mKmK)

- Vileno, L. (2007). From paper to electronic: the evolution of pathfinders: a review of the literature. Reference Services Review, 35(3), 434-451. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320710774300

- Way, D. (2010). The impact of Web-scale discovery on the use of a library collection. Serials Review, 36(4), 214-220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.serrev.2010.07.002

- Wells, D. (2016). Library discovery systems and their users: a case study from Curtin University Library. Australian Academic and Research Libraries, 47(2), 92-105. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2016.1187249

- Wilkes, J., & Gurney, L. J. (2009). Perceptions and applications of information literacy by first year applied science students. Australian Academic and Research Libraries, 40(3), 159-171. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2009.10721402

- Yeager, H. J. (2017). Using EZproxy and Google Analytics to evaluate electronic serials usage. Serials Review, 43(3-4), 208-215. https://doi.org/10.1080/00987913.2017.1350312

- Yeo, P. P. (2011). High yields from course guides at Li Ka Shing Library. Singapore Journal of Library and Information Management, 40, 50-64. https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1013and context=library_research (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3bk8ufT)