Expert power as a constituent of opinion leadership: a conceptual analysis

Reijo Savolainen.

Introduction. Drawing on the typology of social power developed by French and Raven, this paper elaborates the relationships between information behaviour and power by examining how expert power appears in the characterisations of opinion leadership presented in the research literature.

Method. Conceptual analysis focusing on the ways in which expert power are constitutive of the construct of opinion leadership.

Analysis. The study draws on the conceptual analysis of forty-eight key studies on the above issue.

Results. Expert power refers to the opinion leader’s ability to influence the thoughts, attitudes and behaviour of other people through information sharing, due to the possession of such knowledge and skills valued by others. Expert power originates from superior knowledge and skills acquired by means of active use of mass media in particular. Expert power is used in the process in which opinion leaders share their views in diverse contexts such as consumption and political discussion. The extent to which opinion leaders can use their expert power depends on their position in social networks. The findings highlight the need to rethink the traditional construct of opinion leadership because it increasingly occurs in the networked information environments characterised by growing volatility and scepticism towards authorities such as opinion leaders.

Conclusion. Opinion leadership is a significant form of social influence put into effect through sharing personal views. Expert power is a key constituent of opinion leadership affecting the extent to which views shared by opinion leaders can influence the thoughts, attitudes and behaviour of opinion seekers.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper898

Introduction

Power is a rarely discussed contextual factor in human information behaviour research. However, power can significantly affect the ways in which people seek, access and share information (Heizmann and Olsson, 2015; Introna, 1999; Mutsheva, 2007; Olssson, 2007). The relationships between power and information behaviour appear in many forms, either directly or indirectly. Based on power-based authoritarian control, state-level censorship can directly block access to information of certain type (Wang and Hong, 2010). In consumer online discussion forums, power can appear as an indirect social influence manifesting itself in the judgments offered by the participants; their positive recommendations or critical comments may affect other people’s purchasing decisions (Cheung et al., 2017). The above examples suggest power may incorporate both ‘hard’ (coercive) and ‘soft’ (persuasive) elements when it affects information behaviour.

In human information behaviour research, many of the studies thematizing the issues of power have concentrated on the phenomena of cognitive authority and gatekeeping. Cognitive authority exemplifies constructs in which power mainly appears in a ‘soft’ (persuasive) form. No one is forced to use information sources considered authoritative, but people may prefer them because they believe that sources of this kind offer trustworthy information (Wilson, 1983). Gatekeeping incorporates both ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ elements of power. Gatekeeping regulates access to information, but it can also facilitate access if gatekeepers persuade people to prefer information filtered by them (Barzilai-Nahon, 2008). The present study elaborates the picture of ‘soft’ elements of power in human information behaviour by examining how social influence manifests itself in opinion leadership - a form of information sharing. The study at hand was preceded by two companion articles where Savolainen (2020, 2021) demonstrated that the constructs of cognitive authority and gatekeeping can be elaborated further by examining how social power figures in the conceptualisations of authoritative information sources and gatekeepers.

In general, opinion leaders can be defined as individuals who have a great amount of influence on the attitudes, decision-making and behaviours of other people (Godey et al., 2016; Weimann, 2008). Opinion leadership refers to ‘the degree to which an individual is able to influence other individuals’ attitudes or overt behaviour in a desired way with relative frequency’ (Rogers, 2003, p. 27). From the perspective of human information behaviour, opinion leadership is a relevant phenomenon because it deals with the criteria by which certain individuals are considered influential disseminators of persuasive information. The present investigation departs from the assumption that the ability to influence others views by offering information of this kind is based on social power acquired by the opinion leader. So far, the features of opinion leaders have been widely studied in the fields of communication research, consumer research, management studies, political science and social psychology. However, previous investigations have primarily approached opinion leadership as a communicative phenomenon, without devoting sufficient attention to its nature as a form of information sharing.

To examine the nature of power as a constituent of opinion leadership, the present study makes use of the concept of expert power originally proposed by French and Raven (1959). The main goal is to elaborate the picture of the relationships between human information behaviour and power by examining how researchers have conceptualised the manifestations of expert power in opinion leadership. To this end, conceptual analysis was made by concentrating on forty-eight key studies characterising the features of opinion leadership. The findings contribute to the elaboration of the contextual picture of information sharing, deepening our understanding of the ways in which power as a contextual factor shapes the ways in which persuasive information is disseminated within organisations and social groups.

The rest of the article is structured as follows. First, to provide background, the concepts of power, social power and expert power are characterised, followed by the specification of the conceptual framework, research questions and methodological setting. The main part of the article will be covered by the report of the findings. The article ends with the discussion of the main findings and reflection of their significance.

Background

Approaches to power

Power is a multi-faceted phenomenon that defies any attempts of simple definition (Foucault, 1998; Haugaard and Clegg, 2009; Lukes, 1974). In a classic study on economy and society, Max Weber (1978, p. 53) characterised power as a the ‘probability that one actor within a social relationship will be in a position to carry out his own will despite resistance’ In contrast, Diamond (1996, p. 13) asserted that power is not just the ability to coerce others or to get them to do something against their will, but rather, the ‘ability to interpret events and reality, and have this interpretation accepted by those others’.

The above definitions are helpful for the understanding of power as a fundamental factor shaping human behaviour. It is evident, however, that characterisations such as these are all too general for the analysis of power inherent in opinion leadership. To this end, more specific constructs such as social power are more applicable because opinion leadership is a phenomenon where social influence occupies a major role. In a classic study, French and Raven (1959) suggested that social influence is based on the power relationships between individuals. To examine this issue, they developed a schema of sources of social power by focusing on the modes of interpersonal influence. As a point of departure they assumed that social influence manifests itself in a change in the belief, attitude, or behaviour of a person (the target of influence referred to as person B), which results from the action of another person (an influencing agent, referred to as person A). More specifically, in interpersonal interaction between person A and B, A's control over B is positively related to diverse sources of power. They are, respectively, based on

B's perception that A has the ability to mediate rewards for B in case of B's compliance, B's perception that A has the ability to mediate punishments for B if B fails to conform to A's demand, B's perception that A has a legitimate right to prescribe behaviour for B, B's perception that A has some special expertise, and B's identification with A (French and Raven, 1959, p. 156).

Based on the above assumptions, social power is defined as the potential for social influence, that is, the ability of the agent or power figure to bring about a change in the target, using resources available to him or her (Raven, 2008, p. 1). Such resources are represented in five bases of power (French and Raven, 1959). First, legitimate power, sometimes also called positional power, is the power of an individual because of the relative position and duties of the holder of the position within an organisation. Legitimate power is formal authority delegated to the holder of the position, for example, a police officer. Secondly, referent power is the ability of individuals to attract others and build loyalty. Power of this type is based on the charisma and interpersonal skills of the power holder. Third, reward power refers to the degree to which an individual can give others valued material rewards, for example, an increase of salary. Fourthly, French and Raven identified coercive power which is based on the application of negative influences, for example, the ability to demote or to withhold rewards if the desired actions are not taken.

Finally, as a fifth type of social power, French and Raven (1959) defined expert power, which refers to an individual's knowledge, skills or expertise that are valued and needed by an organisation or social group. Unlike the other bases of social power characterised above, expert power is usually highly specific and limited to the particular area in which the expert is trained and qualified. When individuals such as these have knowledge and skills that enable them to understand a situation, suggest solutions, use solid judgment, and generally outperform others, then people tend to listen to them, trust them and respect what they say. As subject matter experts, their ideas will have more value, and others will look to them for leadership in that area. Therefore, expert power is strongly based on the perceived credibility of the influencing agent (person A). According to Erchul and Raven (1997, p. 139), expert power manifests itself when the target of influence (person B) thinks, ‘I don't really understand exactly why, but A really knows this topic so A must be right’. As the above example suggests, expert power originates from the target's (B) belief that the recommendation by the agent (A) is the best thing to do, but the target may not really understand why it is best. The target is simply relying on his or her faith in the superior knowledge and skills of the agent.

Opinion leadership

The characteristics of the influencing agent, in terms of French and Raven’s (1959) typology, person A, are highly relevant for the description of opinion leaders. The construct of opinion leadership has its roots in the voting behaviour study conducted by Lazarsfeld, Berelson, and Gaudet (1944). They found that during the 1940 U.S. presidential election campaign, most voters got their information about the candidates from other people, that is, self-designated opinion leaders who read about the campaign in the newspapers. Opinion leaders picked up information from the media, and then passed this information on to less-active members of the public. It appeared that during the campaign, word-of-mouth transmission of information played an important role in the communication process, while mass media had only a limited influence on most individuals. The findings were used in the development of the two-step flow of communication model suggesting that ideas flow from the mass media to opinion leaders and then to the general public (Lazarsfeld et al., 1944). The model also assumes that opinion leaders tend to be more highly exposed to the news media content than are non-leaders. The former also tend to process information more efficiently than general people. Because opinion leaders are more interested in public issues and better informed than non-leaders, they often become the main source of impact over the public.

In a later study, to identify opinion leaders in the political field, Katz and Lazarsfeld (1955, p. 276) used a follow-up procedure: they asked their sample to name an expert ‘who keeps up with the news and whom you can trust to let you know what is really going on’ and then interviewed persons named as experts by the sample and then those named by the first expert group. In so doing, they found that opinion leaders in public affairs not only had a reputation for expertise but were also more inclined to acknowledge their own influence on other people. The empirical findings revealed that opinion leaders are ordinary people who happen to be regarded as competent and reliable within their own communities. These people come up with new information, thoughts, and opinions, then disseminate them to the general public. These activities constitute opinion leadership which Katz and Lazarsfeld (1955, p. 138) characterised as ‘leadership at its simplest: it is casually exercised, sometimes unwitting and unbeknown, within the smallest groupings of friends, family members, and neighbors’.

Since the 1950s, research on opinion leadership has followed two main streams (Casalo et al., 2020; Li et al., 2013, pp. 43-44). First, researchers have identified the characteristics and motivations of opinion leaders by focusing on their personal and social characteristics. Secondly, researchers have examined the opinion leaders' role and influence on diverse areas such as decision making, consumer behaviour, political communication and diffusion of innovations. One of the main contributions of this research stream is the development of the diffusion of innovation theory explaining how novel ideas and products become spread throughout a social system (Rogers, 1962, 2003). Drawing on the ideas of the two-step flow of communication model, the above theory proposes that in the diffusion of innovations, early adopters have the highest degree of opinion leadership among the adopter categories. Early adopters have a higher social status, financial liquidity, advanced education and are more socially forward than late adopters (Rogers, 1962, p. 283). Later studies have demonstrated that opinion leaders may greatly affect the promotion and diffusion of new products or services, and thus influence the decision making of other consumers (Cho et al., 2012). Moreover, opinion leaders can have a significant impact in political participation and discussions to sustain any prolonged political action (Himelboim et al., 2009).

Explicating and measuring opinion leadership continues to be an important research topic, as personal influence is widely recognised as a major way to shape public opinion, political behaviour, and diffusion of ideas. With the growing popularity of the Internet as a tool of communication, however, it became evident that Katz and Lazarsfeld’s (1955) classic approach to opinion leadership has to be revised. Until the early 2000s, the majority of studies on opinion leadership focused on face-to-face contact and personal interaction dominated by physical proximity as a necessity for the presence of leadership of this kind (Campus, 2012, p. 53). However, with the technological developments, face-to-face communication is no longer the sole determinant of the personal interaction; opinion leaders and opinion followers are increasingly connected through the Internet, rather than sharing a physical space (Turcotte et al., 2015, pp. 523-525). To share their views, opinion leaders increasingly use social media forums such as blogs, Facebook and Twitter (Luqiu et al., 2019; Weeks et al., 2017). On the other hand, empirical studies on Twitter use have demonstrated that the two-step flow of communication model still has explanatory power because opinion leaders are aggregators of information that they share with their followers (Luqiu et al., 2019, p. 42; Turcotte et al., 2015). Tweets from news outlets are often filtered and they then reach a new audience indirectly through opinion leaders (Wu et al., 2011). However, as reviewed by Karlsen (2015, p. 304), the ideas of the two-step flow of communication model have also been criticised for being a too simple description of communication flows in today’s society. This is because communication not only flows from the mass media to opinion leaders and from them to ordinary citizens; communication also flows from citizens to opinion leaders as well as between opinion leaders. All in all, this suggests that the construct of opinion leadership is in transition and that the ways in which the opinion leader’s expert power manifests itself may appear in new forms in the future. Reflecting these changes, opinion leaders making use of forums such as blogs, Instagram and YouTube are often called social media influencers (Casalo et al., 2020; Freberg et al., 2011).

Conceptual framework and research questions

To examine the nature of power inherent in opinion leadership, the present study makes use of the typology of social power (French and Raven, 1959) reviewed above. Opinion leader is referred to as the influencing agent (person A), while opinion follower or opinion seeker stands for the target of influence (person B). Opinion leadership is understood as a form of human communication in which the opinion leaders shares persuasive information with opinion followers of opinion seekers. Drawing on the ideas of French and Raven, expert power is conceptualised as the opinion leader’s ability to influence the thoughts, attitudes and behaviour of the opinion follower or opinion seeker through information sharing, based on the opinion leader’s superior knowledge and skills in a particular domain. It is further assumed that expert power of this kind is used in situations in which the opinion leader shares his or her views with other people so that such views can influence their thoughts, attitudes and behaviour in particular domains such as consumption, environmental protection, food habits and voting.

As the present investigation concentrates on the manifestations of expert power in opinion leadership, no attention will be paid to the question of whether the views shared by opinion leaders would be constituted by factual information (facts), personal experiences, opinions or a combination of the above elements. It is presumed that in communication processes in which such views are shared, the opinion leaders can variously use the above elements. In this context, factual information (fact) is something that can be checked, backed up with evidence and verified. Personal experience refers to an event or occurrence which leaves an impression on someone, while an opinion is a judgment, viewpoint, or statement that is not conclusive. Therefore, opinion is not always true and cannot be always proven (Carrillo-de-Albornoz et al., 2019).

To examine how expert power figures in opinion leadership, conceptual analysis was conducted by concentrating on two issues. First, an attempt was made to find out how expert power manifests itself in the characterisations of opinion leaders if they are approached as holders of such power. Second, how the use of expert power manifests itself in the characterisations of opinion leadership was examined, that is, in processes in which opinion leaders as holders of expert power make attempts to influence other people. Drawing on the above framework, the present study addresses the following research questions:

- RQ1. In which ways have researchers characterised opinion leaders as holders of expert power?

- RQ2. How have researchers characterised the ways in which opinion leaders use their expert power while sharing their views?

To strengthen the focus of the study, no attention will be devoted to the ways in other forms of social power identified by French and Raven (1959), that is, legitimate, coercive, referent and reward power figures in opinion leadership. Secondly, the study will not examine how expert power manifests itself in information behaviours of opinion followers or opinion seekers. It is obvious that the examination of the above issues would require a separate study.

Research material and analysis

The research material was identified by searching seven major databases: Ebsco Academic Search Ultimate, Google Scholar, LISA, Sage, Science Direct, Scopus and Springer Link. The search terms included opinion leader, opinion leadership, power, social power and information sharing. In addition, combinations of search terms were used, for example, opinion leadership AND power, and opinion leader AND social power. The searches resulted in the identification of sixty-four potentially relevant studies published within the period of 1944 - 2020. The preliminary analysis revealed that many of these investigations are less relevant for the present study because they devote marginal attention to power-related issues of opinion leadership. After having excluded investigations of this kind, altogether forty-eight studies directly relevant for the present study were included in the final sample. Most of these studies are journal articles and book chapters. The final sample was chosen by two criteria. First, the studies characterised opinion leaders as actors qualified by knowledge, skills indicative of the base of expert power. Secondly, these studies explicated how the opinion leadership process was conducted as a form of social influence, thus indicating the ways in which opinion leaders use their expert power.

The research material consisting of forty-eight key studies was scrutinised by means of conceptual analysis (Furner, 2004). First, to obtain on overview, the research material was read carefully. The material was then coded by the present author for the conceptual analysis. This method treats the components of the study objects as classes of objects, events, properties, or relationships. More precisely, the analysis involves defining the meaning of a concept and its attributes by inductively identifying and specifying the contexts in which it is classified under the concept in question. To conduct the conceptual analysis, relevant text portions (paragraphs and sentences) characterizing the main object of the study, i.e., opinion leadership were identified. The text portions were equipped with codes indicating how the characterizations of opinion leaders are descriptive of expert power. Similarly, codes were assigned to text portions indicative of how the expert power is used.

More specifically, following Furner’s (2004) terminology, attributes indicative of opinion leaders as holders of expert power were identified from the coded material. Attributes of this kind included the type of opinion leader as a holder of expert power, e.g., early adopter (Rogers, 2003), knowledge broker (Burt, 1999) and ‘influential’ (Weimann, 1994). Moreover, attributes indicating how the expert power is used included the processes of opinion leadership, e.g., spanning ‘structural holes’ (Burt, 1999), generating greater public attention to news coverage (Nisbet and Kotcher, 2009) and tweeting on political issues (Park, 2013). The coding was rendered difficult in that the characterisations of expert power were sometimes intertwined with those typical to referent power wielded by opinion leaders. In this case, the focus was placed on the characterizations indicative of expert power, while the aspect of referent power was ignored. Finally and most importantly, the conceptual analysis was conducted by scrutinizing the similarities and differences between diverse characterizations depicting how expert power figures in opinion leadership. If needed, the research material was revisited by checking details in order to ensure that there are no anomalies.

Findings

Opinion leaders as holders of expert power

The conceptual analysis revealed that opinion leaders share some typical characteristics. Katz (1957, pp. 72-75) was among the first scholars making attempts to specify them. He identified three criteria that distinguish the opinion leaders from non-leaders or opinion followers:

- Who one is: the personal traits and values of the opinion leader

- What one knows: the competence or knowledge related to the leaders

- Whom one knows: the strategic location in the social network.

Of these criteria, the first two are relevant for the analysis of opinion leaders as holders of expert power, while the third criterion mainly deals with the contextual factors of expert power use. The first criterion relates to the traits and values of opinion leaders. Such characteristics may vary widely, depending on who is recognised as an opinion leader. Examples of opinion leaders include scientists, political party leaders, environmental activists, media professionals such as TV hosts and celebrities of entertainment industry (Stehr et al., 2015). The traits and values of opinion leaders include, among others, self-confidence (Nisbet, 2006), intelligence, risk preference and credibility (Weimann, 1994).

The second criterion proposed by Katz (1957) is most pertinent to the analysis of opinion leaders as holders of expert power because competence expresses opinion leaders’ level of expertise on certain subjects. For example, Coulter, Feick and Price (2002) found that expert knowledge in the domain of influence is the most important source of opinion leadership. Many of the early studies on opinion leadership suggested that opinion leaders do not necessarily hold positions of power and/or prestige, but their area of expertise allows them to provide their followers with information and advice (e.g., Katz, 1957, p. 73). Opinion leaders are considered experts in their field, but this is often an informal recognition by close friends, relatives, co-workers, colleagues, and acquaintances (Weimann et al., 2007). However, competence and superior knowledge are features that are not only attributed to opinion leaders by opinion followers. Empirical studies have revealed that opinion leaders tend to perceive themselves as intelligent and independent enough to form personal judgments about public issues that they can share with others (Chan and Misra, 1990).

In general, the opinion leader’s expert power can be based on three sources (Vigar-Ellis et al., 2015, p. 307). First, there is his or her familiarity with an issue or topic, based on the accumulated number of experiences dealing with it. Secondly, expert power can draw on objective knowledge about the issue or topic; this source refers to knowledge that the individual truly possesses and can demonstrate. It includes both the cognitive structures and processes that determine expertise and the knowledge the person has stored in memory. Individuals exhibit objective knowledge on a topic when they are able to give the correct answers to questions about that topic. Thirdly, expert power draws on subjective knowledge indicative of what individuals believe they know about a particular topic; these perceptions correctly or incorrectly reflect objective knowledge about it. Expertise owned by an individual can variously be constituted by the above three elements. Thus, the bases of expert power can incorporate objective (factual) knowledge, as well as subjective knowledge and long-time familiarity with an issue.

Early studies on opinion leadership suggested that the opinion leader’s expert power is mainly based on the fact that compared to opinion followers, opinion leaders pay more attention to media reports and news specific to their domain of interest (Lazarsfeld et al., 1944; Katz, 1957; Katz and Lazarsfeld, 1955). For example, it appeared that political opinion leaders pay more attention to political news, whereas fashion leaders turn more strongly toward fashion news. Moreover, opinion leaders pursue their topics of interest over a longer period and develop a high level of domain-specific knowledge. On the other hand, opinion leaders not only provide information, they also actively seek it (Nisbet, 2006). Many studies indicate that opinion leaders use media, especially print news, more than the general population (Keller and Berry, 2003; Shah and Scheufele, 2006). Overall, the above characterisations suggest that compared to opinion followers, opinion leaders are individuals who have more interest in information about particular items in their area and who actively enrich the base of expert power by seeking information.

Later studies have confirmed the assumption that the opinion leader’s base of expert power is context-specific. For example, the study of the expertise of political party activists in Italy revealed that most of them have a recognised proficiency in politics: many of them have political training organised by political parties, unions or related associations (Vergani, 2011, pp. 75-76). The activists reported that their specific political training allowed them to successfully face the talks with ordinary people of the local community, especially if angry or disillusioned with party politics. In addition to having a strong theoretical background, the party activists recognised as opinion leaders actively updated their knowledge about political issues. They used the media more than the others, gathering all the information that they need in order to lead and to stay abreast of what is happening, and always paying attention to the quality of the information sources. Activists read daily many local and national newspapers and relied more these information sources than TV channels.

The studies on the diffusion of innovations have identified almost similar characteristics of opinion leaders. In an early contribution on this topic, Rogers (1962) depicted opinion leaders as individuals who are more exposed to all forms of external communication, have somewhat higher socioeconomic status, are more innovative, and are at the middle of interpersonal communication networks. Therefore, opinion leaders tend to view themselves as the pioneers of social trends, and early adopters of innovations. Opinion leaders of this type are also more likely to be interconnected to other people than opinion followers (Rogers, 1962). Through these networks, opinion leaders can exert significant impacts on others in societal groups and organizations. Influential individuals such as these can be characterised as holders of elevated social capital, based on their well‐developed meta‐abilities such as excellent cognitive skills, self‐knowledge, emotional resilience and personal drive (Smith, 2005, p. 568).

Even though opinion leadership is increasingly taking place in the forums of social media, there is no consensus among researchers about how these developments would change the opinion leaders’ bases of expert power. Similarly, as in the pre-internet era, opinion leaders can be characterised as innovative and highly knowledgeable individuals who are well connected in social networks, highly influential, and take initiative in discussion. For example, in online discussion groups opinion leaders tend to post the most comments and are active in synthesizing the posts of others (Park and Kaye, 2017, p. 175). Moreover, in specific contexts such as political debates, the social position of the Twitter user matters. In an empirical study focusing on Catalan parliamentarians’ Twitter use, Borge Bravo and Esteve Del Valle (2017) demonstrated that highly visible politicians such as party leaders were followed, retweeted, and mentioned most frequently. More generally, this suggests that similar to traditional (off-line) contexts of opinion leadership, the social influence exerted by opinion leaders in the forums of social media draws on their expert power. It originates from their superior knowledge about an issue within a social group. The base of such knowledge is strengthened by the central position of the opinion leader in a social and organizational environment, enabling early and sometimes privileged access to strategically important information.

Using expert power in the process of opinion leadership

Opinion leaders use their expert power while making attempts to influence other people by sharing their views. Since the 1940s, researchers have depicted diverse ways in which power use of this kind manifests itself. Early studies focused on interpersonal discussion as the primary way in which opinion leaders shared their views about political campaigns (Lazarsfeld et al., 1944). To this end, opinion leaders picked up information from the media and passed it on to less active and less interested people via interpersonal communication. Katz and Lazarsfeld (1955) defined this pattern as a ‘relay function’. In interpersonal discussions, opinion leaders not only directed the attention of others to a particular issue but also signalled how others should respond to it. Later studies have described how opinion leaders influence everyday decisions in public affairs, movie-going and consumer behaviour by sharing their views on the media or through personal contact (Jucquois-Delpierre, 2007, p. 246).

However, later investigations have specified the above picture by demonstrating that opinion leaders transfer only some information from the media, that is, information they consider particularly important or useful to ensure the stability of their social network. In doing so, they select the information and also fulfil a gatekeeper function (Turnbull and Meenaghan, 1980; Stehr et al., 2015, p. 986). In addition to transferring such information, opinion leaders evaluate information before it is shared to others. Moreover, in cases of behavioural uncertainties such as controversial views on the usefulness of an innovation within a social group, opinion leaders provide social guidance and orientation by legitimizing a decision or an innovation (Grewal et al., 2000). Expert power is also used when opinion leaders inform their followers by making complicated topics comprehensible for the audience (Stehr et al., 2015, pp. 991-992). In this case, the use of expert power manifests itself in orientation when opinion leaders communicate their views related to controversial issues by offering certain values, norms, and political attitudes for their followers. Opinion leaders may also elicit interest in certain issues by broadening the followers’ horizons and getting them more involved in new or previously unnoticed topics. This process is particularly characteristic of innovation diffusion (Smith, 2005, p. 568). Early adopters can decrease uncertainty about a new idea by adopting it and by then conveying a subjective evaluation to people potentially interested in an innovation.

As noted above, Katz (1957, pp. 72-75) pioneered by identifying criteria by which opinion leaders distinguish from opinion followers. The criterion of ‘whom one knows: the strategic location in the social network’ is particularly relevant for the analysis of how opinion leaders use their expert power by influencing people in social environments. The strategic social location referred to by Katz concerns the size of their network, more precisely, the number of people who value their leadership in the particular area of expertise. This criterion is closely related to the assumption that opinion leaders are attributed social power due to their standing in the community (Weimann et al., 2007, p. 174). Such persons can be referred to as ‘the influentials’ because they often have higher levels of interest, knowledge, and recognition about social issues than non-leaders (Weimann, 1994). Due to this interest, opinion leaders tend to be more involved in various social activities and social organizations and occupy central positions in their personal networks. This provides opinion leaders with better opportunities to have direct or indirect personal influence on the thoughts, feelings, and actions of others in a social group.

The emphasis on the significance of the opinion leader’s position in his or her personal network suggests that the use of expert power is not merely dependent on how competent or innovative an opinion leader is. Instead, the influence exerted by an opinion leader is explained by his relative position in a social environment. Perhaps the most influential example of studies advocating this view was conducted by Burt (1999). He argued that opinion leaders function as ‘knowledge brokers’ in the social environment and that they gain influence through ‘spanning structural holes’ in such contexts. The construct of structural hole is based on the assumption that information circulates more within than between groups and that weaker connections between groups are holes in the social structure of the groups. Holes of this kind create a competitive advantage for an individual whose social relationships can span such holes. Structural holes are thus an opportunity for the opinion broker to facilitate the flow of information between people. The more an individual is at the centre of qualitatively and quantitatively relevant social relations within the social group, the more he or she has the possibility to influence others’ point of view, and to change the others’ behaviour (Vergani, 2011, p. 73). Opinion leaders gain influence not only because they have contacts with members outside of the group but also because they possess contacts that other group members lack. These contacts provide opinion leaders with unique access to potentially valuable information (Burt, 1999). This strengthens their bases of expert power and enable opinion leaders to use such power by means of interpreting and sharing information obtained outside the social group.

Drawing on the above ideas, Roch (2005, 126-128) questioned the traditional assumption that opinion leadership is singularly rooted in the presence of a certain predisposition or set of personal characteristics such as intelligence. In an empirical study focusing on opinion leadership in an educational context Roch demonstrated that while opinion leaders possess attributes that distinguish them from non-leaders, the social context plays a key role in determining opinion leadership. Therefore, spanning structural holes has a greater effect on the likelihood of being considered an opinion leader than attributes such as the use of media and involvement in the schools. This suggests that opinion leaders may not be more informed than other citizens; however, they are more informed than others in the same social network. Therefore, active information acquisition to increase one’s expert power is not always sufficient to lead one into opinion leadership. Yet, as Roch (2005, pp. 126-128) concluded, certain baseline characteristics also appear necessary for opinion leadership. While it is possible to imagine groups of uninformed individuals in which it would take very little effort to be an opinion leader, it appears unlikely that an individual who pays no attention to the media or engages in almost no interpersonal discussion could act as an opinion leader.

Regardless of whether expert power use is mainly based on the opinion leader’s personal characteristics or his or her central position in a social group, the ways in which power use manifests itself can vary considerably in diverse contexts. For example, opinion leaders with expertise in the issues of climate change can boost the public’s cognitive engagement with that issue, increase their knowledge of the scientific and policy details, promote mobilizing information on how to get personally involved in climate protection, generate greater public attention to news coverage and other available information sources, increase the frequency of public discussion and advocate climate change as a political priority (Nisbet and Kotcher, 2009). Drawing on their expertise, opinion leaders may also make attempts to change consumers’ purchasing behaviour and generate consumer demand for products, services, and energy sources that meaningfully reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The process of opinion leadership has become more complex with the growing use of the forums of social media in particular. Views shared in blogs, Facebook, Twitter and online discussion forums hold remarkable potential to influence the thoughts, attitudes and behaviour of other people. Therefore, might bloggers and Twitter users be the “new” opinion leaders who differently make use of their expert power in online forums?

The conceptual analysis revealed that so far, no conclusive answers are available to the above question. On the one hand, there are critical voices doubting the potential of social media as an arena in which opinion leaders can exert significant influence on others. For example, Castells (2007, p. 247) asserts that a large number of bloggers tend to blog for themselves rather than for their audience. In his view, a good share of this form of mass self-communication is closer to ‘electronic autism’ than to actual communication that is intended to influence the views of other people. This is because ‘any post in the Internet, regardless of the intention of its author, becomes a bottle drifting in the ocean of global communication, a message susceptible of being received and reprocessed in unexpected ways’ (Castells, 2007, p. 247). In such a volatile context, it is less likely that those intense and regular interactions, which are required to exert an effective influence by means of opinion leadership, will be developed.

An opposite view is presented by Song et al. (2007, p. 971) asserting that in fact, opinion leaders exert social influence in the conversations occurring in the blogosphere. More recently, Walter and Brüggemann (2020) demonstrated that under certain circumstances people can become opinion leaders on social media without having previously been exposed to news media content. In this case, the opinion leader’s expert power is not based on the interpretation and filtering of information obtained from second-hand sources such as newspapers; instead, opinion leaders have access to first-hand knowledge on which their expert power in a situation is based. To test this assumption empirically, Walter and Brüggemann used data from the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21). Attendees of the conference had direct information about what was happening during the meeting, and they were able to share such information on Twitter with their followers. These findings suggest that the concern about the demise of opinion leaders with expert power seems to be premature. Opinion leaders, who in the original conceptualization by Lazarsfeld et al. (1944) were emphasised as the nodes that connect the mass medium and the interpersonal networks, are most likely equally essential in the flow of communication occurring in online forums (Karlsen, 2015, p. 302). Casalo, Flavian and Ibáñez-Sánchez, 2020) have recently demonstrated that the advent of the Internet has rather increased than undermined the role of opinion leaders in diverse domains of everyday life. For example, in the fashion industry opinion leaders have become important sources of advice for other consumers, and Instagram is one of the most used platforms by opinion leaders in this particular domain.

Discussion

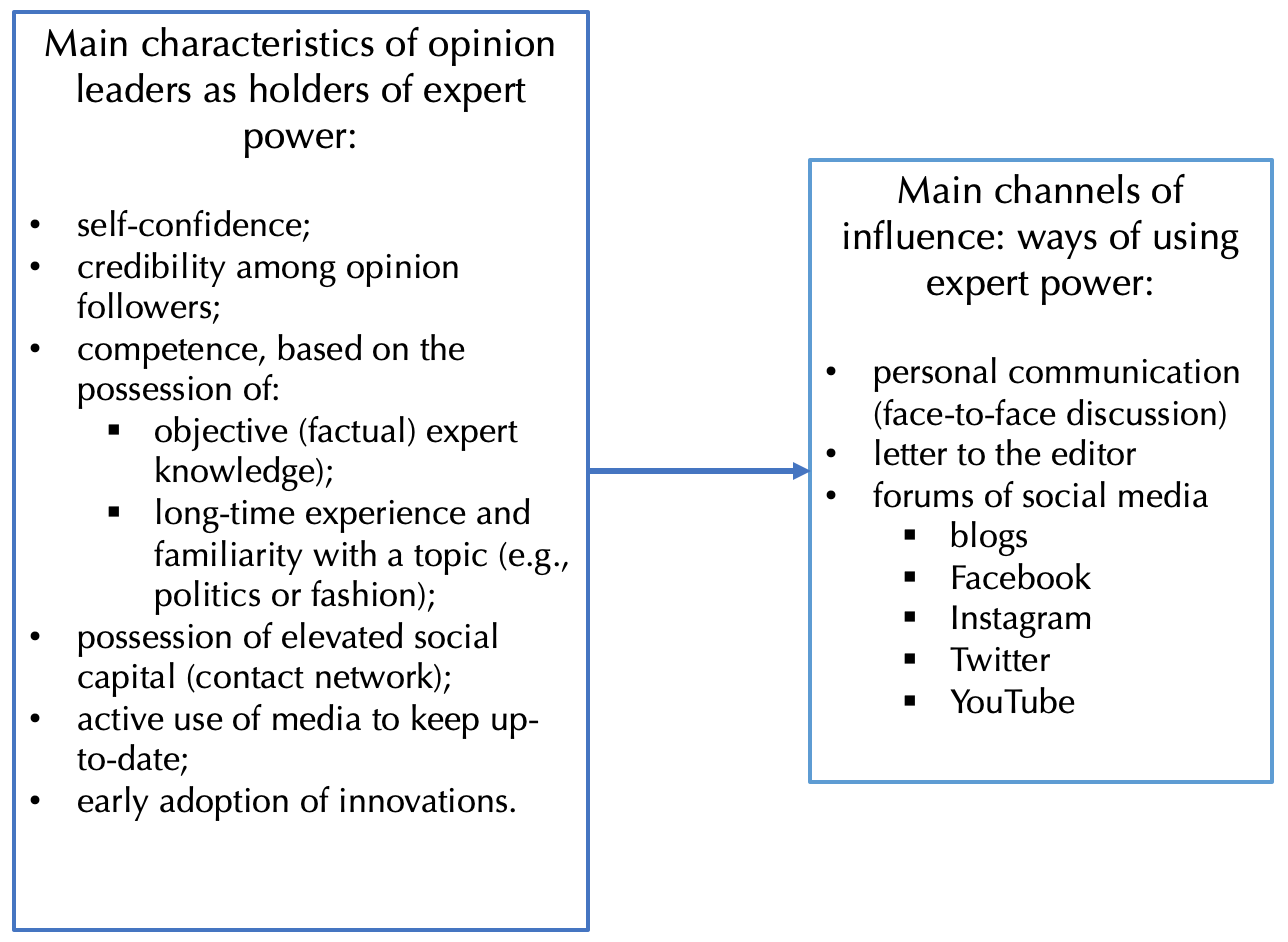

The present study contributed to human information behaviour research by examining an under-researched topic, that is, how power figures in opinion leadership - a form of information sharing. Drawing on the ideas of French and Raven (1959), this was achieved by conceptual analysis of forty-eight key studies characterising the features of expert power inherent in opinion leadership. The main findings are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Summary of the main findings

The first research question focused on how researchers have characterised opinion leaders as holders of expert power. This issue was specified by drawing on the criteria by which opinion leaders can be distinguished from opinion followers or opinion seekers (Katz, 1957, pp. 72-75). First, the opinion leader’s base of expert power may be specified by analysing ‘who one is’, that is, his or her personal characteristics and values. Second, by analysing ‘what one knows’, it is possible examine the competence (knowledge and skills) actually possessed by opinion leaders or attributed to them by opinion followers.

The findings indicate that the opinion leader’s expert power is a relational variable because it is based on superior knowledge and skills of an individual in a specific domain. Expert power refers to the opinion leader’s ability to influence the thoughts, attitudes and behaviour of other people, due to the possession of superior knowledge and skills valued by others. The expert power is due to the fact that, compared to opinion followers or opinion seekers, opinion leaders tend to be more active users of mass media and information sources of other types in a domain they are interested in. Moreover, as demonstrated by the studies on early adopters in particular, opinion leaders tend to be more interested in novel ideas and innovations. All in all, the findings suggest that the opinion leader’s expert power is variously based on the opinion leader’s objective and subjective knowledge about an issue, as well as his or her familiarity with it.

The second research question dealt with the ways in which opinion leaders use their expert power while sharing their views. Regarding Katz’s (1957, pp. 72-75) criteria for identifying opinion leaders, the question of ‘whom one knows’ is important for the analysis of expert power use because it deals with social influence exerted by opinion leaders within a social environment. The findings indicate that in the pre-internet era, expert power use mainly occurred in the context of interpersonal (face-to face) communication between opinion leaders and opinion followers or opinion seekers. In interpersonal discussions, opinion leaders not only helped to direct the attention of others to a particular issue but also suggested how others should act while making of everyday decisions in everyday contexts such as making voting or purchasing decisions. This process is also characteristic of opinion leaders who are considered as early adopters of innovations. Opinion leaders of this type are people whose conversations make innovations contagious for the people with whom they speak. Opportunities to use expert power are enhanced if opinion leaders are involved in various social activities and occupy central positions in their personal networks. On this basis, they acquire social capital that enables them to act as knowledge brokers spanning structural holes in social environments (Burt, 1999). From this perspective, the use of expert power is not simply tied to a set of personal characteristics such as knowledge and skills possessed by an individual; instead, power use also depends on the nature of the social environment in which the opinion leader is embedded.

The findings also suggest that the opinion leader’s ways of using expert power have become more complex in the forums of social media in particular. Views shared in blogs, online discussion forums and Twitter hold remarkable potential to influence the thoughts, attitudes and behaviour of other people. In these forums, the opinion leaders’ expert power use does not only manifest itself in the interpretation and selective dissemination of information published in mass media sources; opinion leaders also create new information which is shared in blog writings and tweets. Moreover, in online discussions, they may use their expert power by summarizing and interpreting messages posted by other participants, thus creating possibilities for social influence. On the other hand, there is no consensus among researchers about the extent to which the opinion leaders’ attempts to influence people’s thoughts and behaviour would be successful because blog writings and other messages posted to social media forums may remain unnoticed. Opinion leaders may succeed fairly well in online political discussion, especially within homogeneous networks by reinforcing consistent individual opinions and questioning contrasting views. However, as Campus (2012, p. 49) has aptly pointed out, there is no conclusive evidence of the extent to which the validation of information shared in online debates depends on the expertise of discussion partners considered as opinion leaders. Overall, there are no conclusive findings indicating how strongly (or weakly) the opinion leader’s expert power would ultimately influence the views of other people.

Due to the paucity of prior studies examining the relationships between power and information behaviour, the evaluation of the novelty value of the findings of the present investigation is rendered difficult. The closest opportunity for comparative notions is offered by two companion studies conducted by the present author. A conceptual analysis examining the manifestations of expert power in cognitive authority revealed that prior studies on this topic have characterised cognitive authorities as information sources that people consider competent and trustworthy in a particular subject area (Savolainen, 2020). Cognitive authorities as holders of expert power have been depicted by diverse qualifiers such as professional credentials, prestigious publication forum and a person’s experiential knowledge on a topic. Moreover, social power of this type figures in self-claimed expertise which is based on long-time experiential knowledge about health-related issues such as self-care of diabetes. Therefore, an individual with self-claimed expertise can be a cognitive authority to herself, as well as to others.

In a related conceptual study, the focus was placed on the characterizations of expert power inherent in gatekeeping (Savolainen, 2021). The findings demonstrate that the expert power attributed to gatekeepers originates from an individual’s specific position or task in an organization or societal group. However, the expert power constitutive of the gatekeeper is not always based on the professional credentials. Similar to a cognitive authority, the gatekeeper’s expert power may be based on an individual’s long-time experiential knowledge about health-related issues, for example. Self-expertise thus acquired can be used while sharing health-related information in the forums of social media in particular. All in all, superior knowledge and skills in a specific domain, coupled with a gatekeepers specific position in a social group or an individual’s ability to control access to information, as well as to filter it are the major qualities constitutive of the gatekeeper’s expert power.

The above findings suggest that the manifestations of expert power in cognitive authority, gatekeeping and opinion leadership have more similarities than differences. Expert power figures in all three constructs in the form of knowledge and skills acquired by a person who occupy an influential position in social networks. The main difference is that expert inherent in cognitive authority is more strongly based on the beliefs that a person is competent and trustworthy as a source of information, whereas the construct of opinion leader emphasizes more the role a person as a broker of current ideas or social innovations. To compare, expert power in gatekeeping places more emphasis on how gatekeepers control access to information sources and filter information before it is shared to others, whereas opinion leaders are primarily associated with attempts to influence people’s view by actively sharing one’s personal views.

The findings of the present investigation also have additional implications for the study of the relationships between power and information behaviour. Jung and Kim (2016) have drawn attention to the fact that the complex and contradictory findings about the relationship between opinion leadership and opinion followership are further reinforced by critical changes in the social and communication environments. Compared to the mid-20th century when the concept of opinion leadership was first introduced, people’s membership and belongingness to social communities have weakened. Many of the early studies examined opinion leaders and opinion followers in geographically well-defined and relatively small community contexts (Rogers and Cartano, 1962). In such contexts it was easier to distinguish opinion leaders from opinion followers, as well as to identify bases of expert power characteristic of opinion leaders. In current social environment, the picture of opinion leaders and the nature of their expert power has become fragmented. However, as Schäfer and Taddicken (2015, p. 962) have pointed out, opinion leaders of our time might be even better equipped to offer advice and opinion more effectively by combining multiple modes and tools of communication. Individuals of this kind may be labelled as ‘mediatised opinion leaders’ who offer information and give advice using diverse channels of communication: face-to-face, interpersonal media and online media (Schäfer and Taddicken, 2015, p. 973). It is evident that opinion leaders of this type have a considerable amount of expert power which is used to provide other people with advice, recommendations and informational support of diverse kind.

In recent years, similar to cognitive authority and gatekeeping, the issues of opinion leadership have become more complicated due to the emergence of post-truth politics. It is characterised by the dissemination of mis- and disinformation in the form of ‘alternative’ facts, fake news and false rumours in the forums of social media in particular (Lee and Choi, 2018; Viviani and Pasi, 2017; Zhou et al., in press). In a recent investigation focusing on Scottish citizens’ perceptions of the credibility of online political facts Baxter, Marcella and Walicka (2019) found that among the study participants, friends and family dominated when it came to fact checking as a first resort. Participants struggled to identify actual agencies of experts whom they would consider reliable and consult to check a fact. Similarly, Gibson and Jacobson (2018) have drawn attention to the uncertainty of the social media environment, characterised by competing information 'bubbles' and the swirling cacophony of competing viewpoints challenging anyone seeking a firm ground for reasoned debate, reflection, and discussion. If this trend continues, the exerting of social influence through opinion leadership may no longer be based on expert power which draws on facts and well-founded personal opinions. It is likely that partisan agendas irrespective of truth, evidence, logic or facts, as well as affective elements such as the expression of negative emotions may occupy a more prominent role in opinion leader’s attempts to influence people’s thoughts, attitudes and behaviour.

Conclusion

The present study clarified the nature of expert power as a constituent of opinion leadership by focusing on the role of opinion leaders. The findings highlight that the opinion leader’s expert power, conceptualised as an ability to influence the thoughts, attitudes and behaviour of other people through information sharing, is a context-specific factor. Expert power originates from the opinion leader’s superior knowledge and skills in a particular domain, valued by opinion followers or opinion seekers. Expert power is used when opinion leaders make attempts to influence other people by sharing their views through interpersonal communication or posting messages to social media forums. The findings also highlight the need to rethink the traditional construct of opinion leadership because it increasingly occurs in the networked information environments characterised by growing volatility and scepticism towards information intermediaries such as opinion leaders.

As the present investigation is just one of the first steps to thematise power as a contextual factor of information behaviour, additional research is required to elaborate the ways in which social power figures in information seeking and sharing. One of the issues worth additional investigation is how social power of other types figures in opinion leadership. In particular, referent power is interesting in this regard because opinion leaders usually tend to be similar in terms of education, social status, and beliefs with their opinion-seeking counterparts (Karlsen, 2015, p. 315; Weimann et al., 2007, p. 174). Additional studies are also required to examine how expert and referent power manifest in the relationships between opinion leaders and opinion followers. Finally, as opinion leadership is closely related to cognitive authority and gatekeeping, comparative investigations focusing on the role of social power inherent in the above constructs would not only shed further light on their similarities and differences but also illuminate the nature of power as a contextual factor shaping human information behaviour more generally.

About the author

Reijo Savolainen is Professor Emeritus at the Faculty of Information Technology and Communication Sciences, Tampere University, Kanslerinrinne 1, FIN-33014 Tampere, Finland. He received his PhD from University of Tampere in 1989. His main research interests are in theoretical and empirical issues of everyday information practices. He can be contacted at Reijo.Savolainen@tuni.fi

References

Note: A link from the title is to an open access document. A link from the DOI is to the publisher's page for the document.

- Barzilai-Nahon, K. (2008). Toward a theory of network gatekeeping: a framework for exploring information control. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 59(9), 1493-1512. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20857

- Baxter, G., Marcella, R. & Walicka, A. (2019). Scottish citizens’ perceptions of the credibility of online political ‘facts’ in the ‘fake news’ era: an exploratory study. Journal of Documentation, 75(5), 1100-1123. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-10-2018-0161

- Borge Bravo, R. & Esteve Del Valle, M. (2017). Opinion leadership in parliamentary Twitter networks: a matter of layers of interaction? Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 14(3), 263-276. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2017.1337602

- Burt, R.S. (1999). The social capital of opinion leaders. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 566(1), 37-54. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271629956600104

- Campus, D. (2012). Political discussion, opinion leadership and trust. European Journal of Communication, 27(1), 46-55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323111434580

- Carrillo-de-Albornoz, J., Aker, A., Kurtic, E. & Plaza, E. (2019). Beyond opinion classification: Extracting facts, opinions and experiences from health forums. PLoS One, 14(1). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6326476/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3dbOYV7).

- Casalo, L.V., Flavian, C. & Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. (2020). Influencers on Instagram: antecedents and consequences of opinion leadership. Journal of Business Research, 117, 510-519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.005

- Castells M. (2007). Communication, power and counter-power in the network society. International Journal of Communication, 1, 238-266. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/46/35

- Chan, K.K. & Misra, S. (1990). Characteristics of the opinion leader: a new dimension. Journal of Advertising, 19(3), 53-60. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1990.10673192

- Cheung, M.Y., Luo, C., Sia, C.L. & Chen, H. (2017). How do people evaluate electronic word-of-mouth? Informational and normative based determinants of perceived credibility of online consumer recommendations in China. In Proceedings of the 11th Pasific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS) (pp. 69-81). Association for Information Systems https://aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1003&context=pacis2007 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3aniy8D).

- Cho, Y., Hwang, J. & Lee, D. (2012). Identification of effective opinion leaders in the diffusion of technological innovation: a social network approach. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 79(1), 97-106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2011.06.003

- Coulter, R.A., Feick, L.F. & Price, L.L. (2002). Changing faces: cosmetics opinion leadership among women in the new Hungary. European Journal of Marketing, 36(11-12), 1287-1308. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560210445182

- Diamond, J. (1996). Status and power in verbal interaction. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Erchul, W.P. & Raven, B.H. (1997). Social power in school consultation: a contemporary view of French and Raven's bases of power model. Journal of School Psychology, 35(2), 137-171. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4405(97)00002-2

- Foucault, M. (1998). The history of sexuality: the will to knowledge. Penguin.

- Freberg, K., Graham, K., McGaughey, K. & Freberg, L.A: (2011). Who are the social media influencers? A study of public perceptions of personality. Public Relations Review, 37(1), 90-92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.11.001

- French, J.R.P. & Raven, B. (1959). The bases of social power. In D. Cartwright (Ed.), Studies in social power (pp. 259-269). University of Michigan Press.

- Furner, J. (2004). Conceptual analysis: a method for understanding information as evidence, and evidence as information. Archival Science, 4(3-4), 233-265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-005-2594-8

- Gibson, C. & Jacobson, T.E. (2018). Habits of mind in an uncertain information world. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 57(3), 183-192. https://journals.ala.org/index.php/rusq/article/view/6603/8821 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2OFWo9K)

- Godey, B., Manthiou, A., Pederzoli, D., Rokka, J., Aiello, G., Donvito, R. & Singh, R. (2016). Social media marketing efforts of luxury brands: influence on brand equity and consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research, 69(12), 5833–5841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.181

- Grewal, R., Mehta, R. & Kardes, F. R. (2000). The role of the social-identity function of attitudes in consumer innovativeness and opinion leadership. Journal of Economic Psychology, 21(3), 233-252. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-4870(00)00003-9

- Haugaard, M & Clegg, S.R. (2009). Introduction: why power is the central concept of the social sciences. In: S.R. Clegg & M. Haugaard (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of power (pp. 1-24). Sage Publications.

- Heizmann, H. & Olsson, M.R. (2015). Power matters: the importance of Foucault’s power/knowledge as a conceptual lens in KM research and practice. Journal of Knowledge Management, 19(4), 756-769. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-12-2014-0511

- Himelboim, I., Gleave, E. & Smith, M. (2009). Discussion catalysts in online political discussions: content importers and conversation starters. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 14(4), 771-789. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01470.x

- Introna, L.D. (1999). Context, power, bodies and information: exploring the 'entangled' contexts of information. In T.D. Wilson & D.K. Allen (Eds), Exploring the contexts of information behaviour. Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Research in Information Needs, Seeking and Use in Different Contexts, 13-15 August 1998, Sheffield, UK (pp. 1-9). Taylor Graham.

- Jucquois-Delpierre, M. (2007). Fictional reality or real fiction: how can one decide? The strengths and weaknesses of information science concepts and methods in the media world. Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society, 5(2-3), 235-252. https://doi.org/10.1108/14779960710837678

- Jung, J-Y. & Kim, Y-C. (2016). Are you an opinion giver, seeker, or both? Re-examining political opinion leadership in the new communication environment. International Journal of Communication, 10, 4439-4459. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/5303/1776 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2OIlFQF)

- Karlsen, R. (2015). Followers are opinion leaders: the role of people in the flow of political communication on and beyond social networking sites. European Journal of Communication, 30(3), 301-318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323115577305

- Katz, E. (1957). The two-step flow of communication: an up-to-date report on a hypothesis. Public Opinion Quarterly, 21(1), 61-78.

- Katz, E. & Lazarsfeld, P.F. (1955). Personal influence: the part played by people in the flow of mass communication. Free Press.

- Keller, E.B., & Berry, J.L. (2003). The influentials: one American in ten tells the other one how to vote, where to eat, and what to buy. Simon & Schuster.

- Lazarsfeld P., Berelson B. & Gaudet, H. (1944). The people's choice: how the voter makes up his mind in a presidential campaign. Columbia University Press.

- Lee, J. & Choi, Y. (2018). Informed public against false rumor in the social media era: focusing on social media dependency. Telematics and Informatics, 35(5), 1071- 1081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.12.017

- Li, Y., Ma, S., Zhang, Y., & Huang, R. (2013). An improved mix framework for opinion leader identification in online learning communities. Knowledge-Based Systems, 43, 43-51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2013.01.005

- Lukes, S. (1974). Power: a radical view. Macmillan.

- Luqiu, R.L., Schmierbach, M. & Ng, Y-L. (2019). Willingness to follow opinion leaders: a case study of Chinese Weibo. Computers in Human Behavior, 101, 42-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.07.005

- Mutsheva, A. (2007). A theoretical exploration of information behaviour: a power perspective. Aslib Proceedings, 59(3), 249-263. https://doi.org/10.1108/00012530710752043

- Nisbet, E.C. (2006). The engagement model of opinion leadership: testing validity within a European context. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 18(1), 3-30. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edh100

- Nisbet, M.C. & Kotcher, J.E. (2009). A two-step flow of influence? Opinion-leader campaigns on climate change. Science Communication, 30(3), 328-354. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547008328797

- Olsson, M. (2007). Power/knowledge: the discursive construction of an author. Library Quarterly, 77(2), 219-240. https://doi.org/10.1086/517845

- Park, C.S. (2013). Does Twitter motivate involvement in politics? Tweeting, opinion leadership, and political engagement. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1641-1648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.01.044

- Park, C.S. & Kaye, B.K. (2017). The tweet goes on: interconnection of Twitter opinion leadership, network size, and civic engagement. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 174-180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.021

- Raven, B.H. (2008). The bases of power and the power/interaction model of interpersonal influence. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 8(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-2415.2008.00159.x

- Roch, C.H. (2005). The dual roots of opinion leadership. Journal of Politics, 67(1), 110-131. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2005.00310.x

- Rogers, E.M. (1962). Diffusion of innovations. 1st ed. Free Press.

- Rogers, E.M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations. 5th ed. Free Press.

- Rogers, E.M. & Cartano, D.G. (1962). Methods of measuring opinion leadership. Public Opinion Quarterly, 26(3), 435-441. https://doi.org/10.1086/267118

- Savolainen, R. (2020). Cognitive authority as an instance of informational and expert power. Manuscript submitted for for review to Libri, (September 2020).

- Savolainen, R. (2021). Manifestations of expert power in gatekeeping: a conceptual study. Journal of Documentation, 76(6), 1215-1232. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-01-2020-0010

- Schäfer, M.S. & Taddicken, M. (2015). Mediatised opinion leaders: new patterns of opinion leadership in new media environments? International Journal of Communication, 9, 960-981. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/2778/1351 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/32aRnsT)

- Shah, D.V. & Scheufele, D.A. (2006). Opinion leaders as information seekers: communication pathways to civic participation. Political Communication, 23(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600500476932

- Smith, P.A.C. (2005). Knowledge sharing and strategic capital: the importance and identification of opinion leaders. The Learning Organization, 12(6), 563-574. https://doi.org/10.1108/09696470510626766

- Song, X., Chi, Y., Hino, K. & Tseng B. (2007). Identifying opinion leaders in the blogosphere. In Proceedings of the 16th ACM Conference on Information and Knowledge Management (CIKM), Lisbon, Portugal, November 2007 (pp. 971-974). Association for Computing Machinery.https://doi.org/10.1145/1321440.1321588.

- Stehr, P., Rössler, P., Leissner, L. & Schönhardt, F. (2015). Parasocial opinion leadership media personalities’ influence within parasocial relations: theoretical conceptualization and preliminary results. International Journal of Communication, 9, 982-1001. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/2717/1350 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2RocQMO)

- Turcotte, J., York, C., Irving, J., Scholl, R.M. & Pingree, R.J. (2015). News recommendations from social media opinion leaders: effects on media trust and information seeking. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 20(5), 520-535. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12127

- Turnbull, P. W., & Meenaghan, A. (1980). Diffusion of innovation and opinion leadership. European Journal of Marketing, 14(1), 3-33. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000004893

- Vergani, M. (2011). Are party activists potential opinion leaders? Javnost - The Public. Journal of the European Institute for Communication and Culture, 18(3), 71-82. https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2011.11009063

- Vigar-Ellis, D., Pitt, L. & Caruana, A. (2015). Does objective and subjective knowledge vary between opinion leaders and opinion seekers? Implications for wine marketing. Journal of Wine Research, 26(4), 304-318. https://doi-org/10.1080/09571264.2015.1092120

- Viviani, M. & Pasi, G. (2017). Credibility in social media: opinions, news, and health information - a survey. WIREs Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 7(5), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1002/widm.1209

- Walter, S. & Brüggemann, M. (2020). Opportunity makes opinion leaders: analyzing the role of first-hand information in opinion leadership in social media networks. Information, Communication & Society, 23(2), 267-297. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1500622

- Wang, S.S. & Hong, J. (2010). Discourse behind the forbidden realm: Internet surveillance and its implications on China’s blogosphere. Telematics and Informatics, 27(1), 67-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2009.03.004

- Weber, M. (1978). Economy and society. An outline of interpretative sociology. University of California Press.

- Weeks, B.E., Ardèvol-Abreu, A. & Gil de Zúñiga, H. (2017). Online influence? Social media use, opinion leadership, and political persuasion. International Journal of Operational Research, 29(2), 214-239. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edv050

- Weimann, G. (1994). The influentials: people who influence people. University of New York Press.

- Weimann, G. (2008). Opinion leader. In The International Encyclopedia of Communication. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405186407.wbieco013

- Weimann, G., Tustin, D.H., Vuuren, D.V. & Joubert, J.P.R. (2007). Looking for opinion leaders: traditional vs. modern measures in traditional societies. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 19(2), 173-190. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edm005

- Wilson, P. (1983). Second-hand knowledge: an inquiry into cognitive authority. Greenwood Press.

- Wu S., Hofman J.M., Mason W.A. & Watts, D.J. (2011). Who says what to whom on Twitter. In Proceedings of the 20th ACM International World Wide Web Conference, Hyderabad, India, 28 March - 1 April, 2011 (pp. 705-714). Association for Computing Machinery. http://www.wwwconference.org/proceedings/www2011/proceedings/p705.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3uNMH8J).

- Zhou, C., Xiu, H., Wang, Y. & Yu, X. (In press), Characterizing the dissemination of misinformation on social media in health emergencies: an empirical study based on COVID-19. Information Processing & Management. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2021.102554