The role of youths’ perceived information literacy in their assessment of youth information and counselling services

Muhaimin Karim, Shahrokh Nikou, and Gunilla Widén.

Introduction. This paper presents empirical research on whether young people’s perceived information literacy influences their perceived service quality of a youth information and counselling agency.

Method. An online survey was distributed and 3,287 responses of young people between fifteen and twenty-nine years old were collected from sixteen different countries across Europe. The survey questionnaire was pre-tested by five academic experts in the field, and by youth information service workers. The SERVQUAL model including constructs (access, reliability, and responsiveness) was used to devise a theory-based conceptual model. Additionally, we used perceived information literacy as an antecedent construct in our model.

Analysis. We applied structural equation modelling to investigate the effect of perceived information literacy and constructs of the SERVQUAL model on perceived service quality.

Results. The results of analysis show that perceived information literacy has a strong influence on perceived ease of access, perceived reliability, and perceived responsiveness, and through these constructs has an indirect effect on perceived service quality.

Conclusions. Results show a clear alignment with existing literature in the areas of youth perceived information literacy and information services. The proposed framework contributes to the scholarly discussion on youth information services and youth perceived information literacy.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper900

Introduction

According to the Association of College & Research Libraries (Association…, 2019), perceived information literacy is the ability of an individual to realise her or his information needs, and the capacity to locate, collect, evaluate, and use the information effectively and responsibly. The advancement in digital technologies has a direct influence on all of the components of perceived information literacy: information needs; location of information; the process of collecting information; and information evaluation and analysis. This is more applicable to young people who, as defined by Prensky (2001a, 2001b), are individuals born roughly after 1990, that grew up with digital technology and, since their birth, have been exposed to digital media, devices, applications, and the Internet, and spend a considerable amount of time online. The adoption of the Internet and digital technologies in their everyday life has changed their collective and individual practices of seeking, retrieving, and evaluating information (Dresang, 2005; Dresang and Koh, 2009; Koh, 2013). Thus, the level of youth’s perceived information literacy in their everyday life can influence their perceived quality of any information service (Shipman et al., 2009), like a library, an archive, or a youth information and counselling agency. In this regard, this assists young people in identifying and evaluating reliable information and responds to youth’s information needs. This has been exemplified by the Website of the European Youth Information and Counselling Agency (hereafter “the European Youth Agency”).

Previous studies showed that an information service is considered to be effective when it is perceived to be responsive, easily accessible, and provides reliable information (Markwei and Rasmussen, 2015). These three components are also present in the SERVQUAL model developed by Parasuraman et al. (1988), which is widely used to evaluate service quality of diverse services, including information services. However, the digital transformation of many routine processes has changed the needs, location, collection, and evaluation of information, particularly among the youth who grew up with new technologies. In this regard, there is a limited understanding in the literature in relation to, for example, how youth work and counselling services must respond to digital-age information behaviour and how to better serve youth’s information needs (Pawluczuk et al., 2019). To bridge this gap, this paper investigates how young people evaluate an information service as an institutional source, and how their everyday-life information literacy influences their perceived service quality from different perspectives, such as accessibility, reliability, and responsiveness of an information service. Studying the role of youths’ perceived information literacy in their assessment of an institutional information source sheds light on the quality of information services and provides complementary insights into how to design information services tailored for the young population.

Thus, this paper aims to build a conceptual model to investigate whether youth’s perceived information literacy in everyday life affects their perceived responsiveness, perceived ease of access, and perceived reliability of an information service, and thus influences their perception of a service quality. The two research questions guiding our study are:

- How do perceived responsiveness, perceived reliability, and perceived access determine the perception of youth towards information and counselling services? and

- Does perceived information literacy of the user influence their perceived responsiveness, perceived reliability, and perceived access of the service?

To find answers for our research questions, we used a modified version of the SERVQUAL model developed by Parasuraman et al. (1988) to build our research model. SERVQUAL is a customer-oriented tool that measures the quality of various services, including information services, and gives detailed recommendations to improve the quality of those services (Pedramnia et al., 2012). In addition to the SERVQUAL constructs, we incorporated perceived information literacy as a predictive variable into our proposed model. The original scales of the service quality model (SERVQUAL) comprise ten dimensions (e.g., access, reliability, and responsiveness of a service). As some of the dimensions were found to be closely related, the ten dimensions were reduced to five and a revised model was suggested (Parasuraman et al., 1991). Other authors such as Dryden (2005) have stressed that the above stated factors (e.g., access, reliability, and responsiveness of a service) potentially impact perceived service quality.

The data used for this study was collected through the Erasmus+ KA2 project, Future Youth Information Toolbox a project created owing to the lack of evidence-based research in the field of youth information. A Europe-wide online survey to young individuals (aged between fifteen and twenty-nine years old), was carried out to identify youth information needs, trends, and most relevant topics (Karim and Widén, 2018). The collected survey data was further analysed for this study, and unlike previous studies, which have largely focused on the library and school contexts, in this paper we position youth in everyday life, non-work contexts, as there is a scarcity of research studying youth information behaviour and their perceived information literacy in such contexts (Qayyum and Williamson, 2014). To analyse the collected data, we applied structural equation modelling, which is an appropriate method for this research, because it allows us to assess the path model and to test hypotheses concerning the relationships between interacting variables. This paper contributes theoretically to research on youth information behaviour and provides new insights and knowledge to practitioners aiming at developing more user-centred youth information and counselling services. Thus, this paper, in addition to theoretical contributions, provides some practical insights into how to improve information services for youth and how to enhance their perceived information literacy, which is vitally important to them and to contemporary society.

In the next section, we elaborate on contemporary youth information behaviour literature and discuss youth perceived information literacy, as well as discussing information and counselling service agencies. The theoretical background and hypothesis development will then be discussed. Research methodology and data analysis and results are then presented, followed by the discussion, conclusions, practical implications, and limitations.

Young people in today’s digital age are described as important contributors and co-constructors of the online information landscape (Subrahmanyam and Smahel, 2010), or as information creators (Koh, 2013). In this 21st century, the prevalence of information technology and the Internet have shaped youth’s behaviour in relation to sources and channels of information, including both active and passive information seeking and information use (Wilson, 2000). For example, print newspaper circulation has been plummeting over the years, with a decline in sales of 30% in the US, 25% in the UK, and slightly less in Greece, Italy, and Canada (Robinson, 2010; Schwartz, 2005). Print media is seemingly losing its young readers simply because they want news on demand, and to control and customise content, time, and the medium itself (Huang, 2009). This phenomenon has been confirmed by publishers, as they shifted youth-related investments into online services. Bowler et al. (2018) argue that there is also evidence that new forms of information behaviour have arisen out of the affordances of mobile technology. For example, smartphones and tablets promoted a quick look into information to fulfil everyday-life needs, and often served as information and game tools. In an investigation titled Net children go mobile (Bowler et al., 2018), the authors found that there were few references to text-based sources, and instead references were to Wikipedia and school-referred websites.

In the aforementioned studies, it was observed that young people preferred information sources to be interactive, visual, and mobile worlds of social media platforms, applications, and game environments. They sought store catalogues, videos to learn languages, music lessons, and shortcuts for games, and they used a combination of search engines and applications for smartphones or tablets. YouTube was found to be a critical information source for teens, who preferred to view, rather than to read. Although young people were found to be aware of Internet threats, speed of information retrieval and rapid assessment of the quality of information continue to be the defining characteristics of young people’s perceived information literacy (Bowler et al., 2001; Rowlands et al., 2008). Moreover, as new formats and channels of information are continuously being developed, the reliability of information is often hard to assess. Besides, young people spend little time evaluating information for its relevance, accuracy, and authority. Since young people have a poor understanding of their information needs, their evaluation of information and its source is often impaired (Bowler et al., 2018; Metzger et al., 2015; Rowlands et al., 2008).

As indicated by the European Youth Agency, youth information counselling services play a crucial role in assisting young people in identifying and evaluating reliable information, thus contributing to young people’s media and perceived information literacy. The youth information and counselling service can be described as an array of various services that aims:

- to provide reliable, accurate, and quality information to the youth;

- to give access to different sources and channels of information;

- to help young people navigate through the information overload they face today;

- to provide support in evaluating the obtained information and in identifying its quality;

- to guide young people in reaching their own decisions and in finding the best options open to them; and

- to offer different channels of communication and dialogue in order to support young people in their search for information and knowledge.

Youth information and counselling agencies aim to provide a participatory environment where young people can actively and independently implement social changes through their access to authentic information. However, as young people continue to advance their digital expertise, there is a demand for improving information and counselling services according to the way they realise their information needs, collect information, and evaluate its use. Because of the fast-paced nature of the information and technological landscape, youth information service agencies require to continuously analyse risks and benefits and make decisions to attend to contemporary youth information behaviour (Batsleer and Davis, 2010). Despite such a paradigm shift in information behaviour, research demonstrates suboptimal information literacy among youth today, as well as suggesting a paucity in research on young people’s perceived information literacy and how they use it to assess institutional information sources (Metzger et al., 2015; Qayyum and Williamson, 2014).

Theoretical background and hypothesis development

Although there have been many studies on youth information behaviour, the literature lacks a theory-based conceptual model that is explicitly developed to explain youth information literacy in assessing the service quality provided by information and counselling agencies. Most prior studies are about the information needs of young people, but rarely has the focus been on the antecedent factors affecting youths’ evaluation of quality of information and information services.

In the absence of sufficient research in this context, this study includes the constructs of the SERVQUAL model developed by Parasuraman et al. (1991, 1988). This evaluation tool has been used to assess information services and information systems in previous studies (Landrum et al., 2004, 2009; Pedramnia et al., 2012). Although the revised version of the SERVQUAL model comprises five dimensions (namely reliability, assurance, tangibility, empathy, and responsiveness), in this paper, we aim to use only three dimensions. The main reason behind this deliberate choice is the context and the type of service being investigated. As we mainly focus on information services provided by counselling service agencies, and not on a particular physical product, the tangibility dimension of the SERVQUAL model seems inappropriate. Moreover, as most interactions between youth and information workers in the counselling service will be through online channels, the construct of empathy was not measured separately. Nevertheless, we do not aim to underrate or underestimate the importance of the tangibility and empathy dimensions.

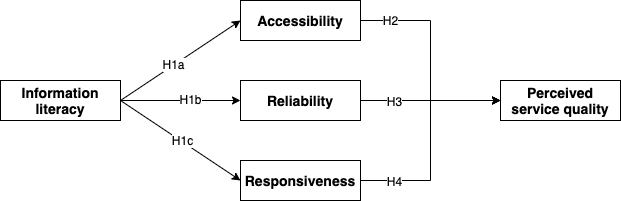

Additionally, the assessment of an information service’s quality could also depend on individuals’ ability in collecting, evaluating, and using information services. Therefore, perceived information literacy will also be used as a determining construct in our proposed conceptual model (see Figure 1), to see how service quality and perceived information literacy are related. In the following subsections, we start by defining perceived information literacy and its relation to the perception of information service quality, followed by a discussion on the three dimensions of the service quality model.

Perceived information literacy

Perceived information literacy is the ability of an individual to understand their information needs; the ability to source them from multiple authentic sources; the ability to validate the reliability of the information; and the ability to use it effectively for decision making (Association..., 2019). Previous studies on literacy and its impact on digital natives and digital immigrants (Nikou et al., 2018, 2019) found that perceived information literacy has a significant relation to attitudes toward using digital technology. Since youth information and counselling service agencies aim to provide necessary information to young people, the ability of young users to comprehend information could influence their perceptions of information service quality.

Young people’s ability to realise their information needs, locate potentially authentic sources, collect information and evaluate it, can largely influence their assessment of the information source. Therefore, perceived information literacy can indeed influence perceived ease of access, perceived reliability, and perceived responsiveness. Apart from providing access to reliable information, youth information and counselling service agencies aim to improve the information and media literacy of the young population. Therefore, we posit that the ability and the level of perceived information literacy of the youth determine how they would perceive the service quality. Thus, we hypothesise:

H1a: Perceived information literacy has a positive effect on the perception of accessibility of information services among youth.

H1b: Perceived information literacy has a positive effect on the perception of reliability of information services among youth.

H1c: Perceived information literacy has a positive effect on the perception of the responsiveness of information services among youth.

Since perceived information literacy is the ability of understanding information needs, searching multiple sources, and validating the authenticity of information, it can be assumed that the relationship between perceived information literacy and perceived service quality will be mediated by accessibility, reliability, and responsiveness of information services. Thus, we hypothesise:

H1d: The relationship between perceived information literacy and service quality is mediated by accessibility, reliability, and responsiveness of information services.

Access

In the information age, easy access to information is a prerequisite for day-to-day functionality and well-being for the youth. Easy access to information affects the perception of service quality provided by, for example, information counselling agencies, as it allows youth to make well-informed decisions and protects them from popular misconceptions about sensitive issues. According to Parasuraman et al. (1985, p. 46), access involves approachability and ease of contact. In other words, the service should be easily accessible by all possible means (physically and virtually).

Moreover, the waiting time to access a service should not be extensive and, at the same time, the service facility’s location should be convenient. Highly appreciated information services are those that are able to ensure timely access to information in their respective disciplines, irrespective of their format. Access, however, is not a mere substitution of print media by electronic formats, but rather the delivery of information when needed, wherever needed, in the medium of choice. Therefore, accessibility to an information service can determine youth perceptions of service quality provided by information counselling service agencies, and we hypothesise:

H2: Accessibility is a significant driver of youth perception of the quality of information services.

Reliability

Another important feature of an information service is reliability. According to the SERVQUAL model, reliability is one of the prerequisites of any service, positively affecting the perception of a service’s quality. An information service could be considered effective when the information they disseminate is considered reliable by the users. Pitt et al. (1995) defined reliability as the ability to perform a promised service dependably and accurately. In library research, there are many aspects of library operations for which unreliable services can be viewed as impediments to self-reliant behaviour, as barriers to the ubiquity and ease of access that users seem to value so highly.

Since youth information and counselling service agencies are committed to deliver authentic information services, reliability seems to be an appropriate factor to assess youth perceptions of information services quality. In this paper, we asked respondents to rate their perceived reliability of the information services they obtain from youth information and counselling service agencies, youth clubs or youth organisations, and youth workers. Therefore, we hypothesise:

H3: Reliability is a significant driver of youth perception of the quality of information services.

Responsiveness

Responsiveness is the third dimension of the SERVQUAL model and is defined as the willingness to help customers and provide a prompt service (Parasuraman et al., 1985). Along with easy access to reliable information, counselling is also a necessary part of information and counselling services. Counselling helps youth to make sense of difficult information, which is very relevant for services aiming to help young and often inexperienced users. The perceived quality of the information and counselling service thus largely depends on how prompt and accommodative the service was in response to the needs of the young users. Since a more empathetic attitude towards the needs of users is likely to make the consumption of the needed information and service more pleasant, we hypothesise:

H4: Responsiveness is a significant driver of youth perception of the quality of information services.

Perceived service quality

Perceived service quality is defined as 'a global judgment, or attitude, relating to the superiority of the service' (Parasuraman et al., 1988, p. 33), a definition many researchers in the service quality literature use. Perceived service quality is the result of a comparison of performance, and what the consumer feels a firm should provide. Thus, it can be argued that one of the main responsibilities of youth information and counselling agencies involves providing quality services, as well as providing access to reliable information in response to youth’s information needs. Dryden (2005) used the original dimensions of the SERVQUAL model and found accessibility, reliability, and responsiveness to be the most important factors in the assessment of library services’ quality. In our model, perceived information literacy, accessibility, reliability, and responsiveness are conceptualised as determinants of perceived service quality (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Proposed conceptual model.

Research method

As mentioned earlier, the study uses the dataset that was collected through the Erasmus+ KA2 project, Future Youth Information Toolbox. The authors (as partners in the project) were involved in the development of the survey questionnaire which was distributed among young people across different countries in Europe. While the project utilised the entire dataset to explore current information needs of the European youth, this study utilised a subset of the data to understand youth’s perceptions of information service quality. Structural equation modelling was used to examine and investigate the relationships between the antecedent factors of perceived service quality. This is a multivariate approach that can be used to evaluate and test the interactions of observed and latent variables. This method was deemed appropriate for the current research, because the core methodological aim was to explore the linear relationships between variables, similar to, but more efficient than, conventional regression analyses (Beran and Violato, 2010). The approach allows testing of the moderation and mediation effect, which are also important aspects in our analysis. The approach has been used in previous studies to evaluate service quality (e.g., De Oña et al., 2013; Saurina and Coenders, 2002).

Data collection

Before, the actual data collection, the survey was pre-tested by five experts in the field, academic professionals, as well as youth information service workers, to obtain feedback and comments regarding the questions and to avoid ambiguous expressions. The survey was administered using the online platform of Survey Monkey. The questionnaire was distributed to young individuals aged between fifteen and twenty-nine years. The convenience sample of young people was collected from sixteen countries (see Appendix B for more information) over the course of sixteen weeks between November 1, 2017 and February 28, 2018.

In total, 7,368 questionnaires were distributed, and after removing incomplete responses, the final dataset comprised of 3,287 responses that met the inclusion criteria. The youth information and counselling services operating in Europe promoted the survey as part of the Future Youth Information Toolbox project, and the survey distribution was coordinated by the European Youth Agency. We did not provide any incentives to youth to participate in this research project. Common method bias can be an issue, especially when the data are collected via self-reports (Chang et al., 2010). Therefore, the respondents were informed that their personal information and responses would be used and treated only at an aggregate level, which enabled us to account for any common method bias issues.

Measurement

All items for measuring the five constructs in the model were drawn from previously validated studies. In this study, accessibility, reliability, and responsiveness of information services were measured using five, five, and four items, respectively. All of the items were derived from Parasuraman et al.’s work (1991, 1988). For example, regarding accessibility, respondents were asked to answer how easy or difficult it is to access the information services provided by information service agencies (Agosto and Hughes-Hassell, 2005; Shenton and Dixon, 2003). To measure service quality, we used five items (Bloemer et al., 1999; Lee et al., 2000). Finally, for measuring perceived information literacy, we used four items derived from the Association of College and Research Libraries' framework for information literacy (Association..., 2019). A five-point Likert scale was used to measure all the items, in total we had twenty-three items in the survey (see Appendix A).

Data analysis and results

In the following sections, we first present and discuss the descriptive analysis; then the measurement results; and finally, we present and discuss the structural results and elaborate on the findings. We used SmartPLS Version 3.0 to assess the path relationships.Descriptive analysis

On average, it took twenty minutes to complete the survey. We divided our dataset into groups, group one contains early respondents and group two contains late respondents; the responses in these two groups were compared. According to t-test results, we did not find any significant differences between the two groups. The average age of the respondents was 19.28 years (range: from 15 to 29 years). Of the respondents, 1,205 (37%) were male and 2,036 (62%) were female; 46 respondents did not answer this question.

Measurement model

We performed a confirmatory factor analysis to assess internal consistency and discriminant validity of the measures. The analysis revealed five factor solutions (see Tables 1 and 2 for correlations between the variables and other descriptive statistics).

| Accessibility | Information literacy | Reliability | Responsiveness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accessibility | — | |||

| Perceived information literacy | 0.264 | — | ||

| Reliability | 0.361 | 0.269 | — | |

| Responsiveness | 0.220 | 0.113 | 0.202 | — |

| Service quality | 0.221 | 0.110 | 0.328 | 0.345 |

With regard to measurement model results, the analysis showed that all the items loaded into their respective constructs. Moreover, we used SmartPLS for the analysis and, recommended by Sarstedt et al. (2014), we used path coefficients and their significance for the model fit. In our analysis, the value of standardised root mean residual was 0.056, and the normed fit index valuewas 0.846.

| Construct | Item | Mean | Std. Dev. | Factor loadings | α* | CR* | AVE* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accessibility | Acc-1 | 3.51 | 1.10 | 0.771 | 0.803 | 0.854 | 0.542 |

| Acc-2 | 3.34 | 1.15 | 0.754 | ||||

| Acc-3 | 3.43 | 1.22 | 0.787 | ||||

| Acc-4 | 3.30 | 1.18 | 0.893 | ||||

| Acc-5 | 3.27 | 1.21 | 0.761 | ||||

| Perceived information literacy | InfLit-1 | 3.73 | 0.89 | 0.833 | 0.864 | 0.907 | 0.710 |

| InfLit-2 | 3.68 | 0.84 | 0.863 | ||||

| InfLit-3 | 3.72 | 0.89 | 0.846 | ||||

| InfLit-4 | 3.66 | 0.87 | 0.826 | ||||

| Reliability | Reli-1 | 3.79 | 1.05 | 0.892 | 0.835 | 0.900 | 0.751 |

| Reli-2 | 3.56 | 1.01 | 0.853 | ||||

| Reli-3 | 2.59 | 1.89 | 0.710 | ||||

| Responsiveness | Res-1 | 3.23 | 1.67 | 0.711 | 0.766 | 0.841 | 0.513 |

| Res-2 | 2.72 | 1.82 | 0.732 | ||||

| Res-3 | 3.40 | 1.72 | 0.700 | ||||

| Res-4 | 3.03 | 1.85 | 0.733 | ||||

| Service quality | SerQu-1 | 3.43 | 1.11 | 0.781 | 0.889 | 0.919 | 0.694 |

| SerQu-2 | 3.79 | 1.01 | 0.859 | ||||

| SerQu-3 | 3.52 | 0.98 | 0.845 | ||||

| SerQu-4 | 3.67 | 0.98 | 0.883 | ||||

| SerQu-5 | 3.34 | 1.04 | 0.792 | ||||

| * α = Cronbach's alpha; CR = composite reliability; AVE = average variance extracted | |||||||

We computed Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability, and average variance extracted to measure internal consistency. Cronbach’s alpha values were all above the recommended cut-off value of 0.70 (range: 0.766 to 0.889). Average variance extracted values ranged from 0.542 to 0.751, Composite reliability values ranged from 0.854 to 0.919, all well above the recommended minimum of 0.50 and 0.70, respectively (Bagozzi and Yi, 1988; see Table 3). Standardised item loadings (twenty-one items in total) for each construct are shown in Table 3, all exceeding the recommended value of 0.70. We had to remove two items from further analysis because of low factor loadings.

We also computed discriminant validity to assess if the square root each construct’s average variance extracted was greater than its highest correlation with any other construct. The test result showed that there was not a discriminant validity issue in the data (see Table 3).

| Accessibility | Information literacy | Reliability | Responsiveness | Service quality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accessibility | 0.675 | ||||

| Perceived information literacy | 0.264 | 0.842 | |||

| Reliability | 0.361 | 0.269 | 0.867 | ||

| Responsiveness | 0.221 | 0.113 | 0.202 | 0.716 | |

| Service quality | 0.221 | 0.112 | 0.328 | 0.345 | 0.833 |

We used the approach recommended by Kock (2015) to assess common method bias, which is based on the variance inflation factor. According to this approach, the value of the variance inflation factor must be lower than 3.3; in this paper, these values at the factor level were lower than 3.3 (range: from 1.294 to 2.857). Thus, we concluded that the model is free from common method bias.

Structural model and hypothesis testing

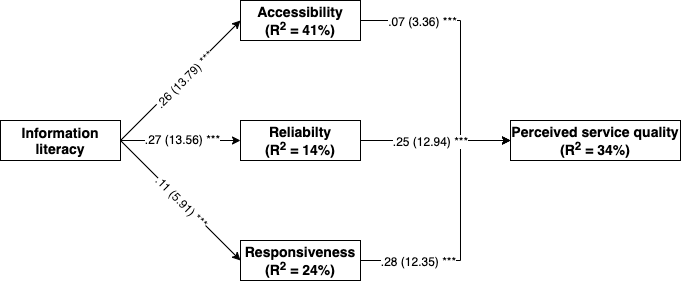

As stated before, structural equation modelling results showed that the structural model has a satisfactory model fit. Standardised path coefficients are shown in Figure 2. The results showed that perception of service quality is explained by a variance of 34%, indicating that the predictors (accessibility, reliability, and responsiveness of information services) together explained a relatively large amount of variation in this construct. Accessibility of information services was explained by a variance of 41%, followed by 14% for reliability and 24% for responsiveness of information services.

Figure 2: Structural model results.

The structural model results revealed that the path between perceived information literacy and accessibility is significant (β = 0.26, t = 13.79, p = 0.001), providing theoretical support to H1a in the model. Moreover, the results revealed that perceived information literacy has a positive direct effect on both reliability (β = 0.27, t = 13.56, p = 0.001) and responsiveness (β = 0.11, t = 5.91, p = 0.001) of information services; thus, H1b and H1c are supported by the model. Moreover, the results revealed that the path between accessibility and perceived service quality is significant (β = 0.07, t = 3.36, p = 0.001), providing theoretical support to H2 in the model. The results also revealed that both reliability (β = 0.25, t = 12.94, p = 0.001) and responsiveness (β = 0.28, t = 12.35, p = 0.001) have a positive significant effect on perceived service quality; thus, H3 and H4 are supported by the model (see Figure 2).

Multigroup analysis

We used the sex of respondents as a control variable in the multigroup analysis. This was done to examine and assess if there were any differences in the path model regarding respondents’ perceptions of information services’ quality. The results revealed some sex differences, such that the path between accessibility of information services and perceived service quality was significant for males (β = 0.11, p < 0.002), but non-significant for females. The parametric test result is: β = 0.11, t = 2.772, p < 0.005; and the Welch–Satterthwaite test result is: β = 0.11, t = 3.731, p < 0.005. Moreover, the results showed that the path between perceived information literacy and accessibility of information services is significant for females (β = 0.10, t = 3.661, p < 0.001), but non-significant for males.

Mediation test

We also performed a mediation test to assess if accessibility, reliability, and responsiveness of information services would mediate the relationship between perceived information literacy and perceived service quality. The mediation test results showed that these three constructs partially mediate this path relationship, such that the total indirect effect is (β = 0.12, t= 10.935, p < 0.001). The specific indirect effect values for accessibility were: β = 0.02, t= 3.351, p < 0.001; for reliability were: β = 0.07,t= 9.412, p < 0.001; and for responsiveness were: β = 0.03, t= 5.324, p < 0.001. With these findings, we thus provide statistical support for H1d.

Discussion

This paper is one of the first to propose a theory-based model to assess youth’s perception of service quality provided by youth information and counselling service agencies. It fulfils the objectives stated in the introduction section by validating an integrated service quality model. The core theoretical objective of this paper was to identify antecedent factors perceived to be important by the youth. To do so, we applied structural equation modelling and used the service quality assessment scales of the SERVQUAL model (Parasuraman et al., 1985, 1988, 1991). In addition, we added perceived information literacy as an independent construct to see how it influences the determinants of service quality. The structural equation modelling results showed significant correlation between each of the predictive variables (i.e., accessibility, reliability, responsiveness, and perceived information literacy) and the outcome variable (perception of service quality).

The structural equation modelling results revealed that the youth considered easy access to various information topics as an important feature for youth information and counselling services. This result matches previous studies where access to information was found to be a significant determinant of perceived service quality (Heath and Cook, 2001). Moreover, these results showed that young people demand prompt information services over any other feature from youth information and counselling agencies. This outcome, again, matches previous studies showing that youth prefer sources that provide quick access to diverse information (Heath and Cook, 2001; Subhash et al., 2018). Reliability of information services was considered to be the second most important factor, which is similar to Heath and Cook ( 2001), who argue that reliability is expected to have greatest influence.

The structural model results also revealed the influence of perceived information literacy on perceived service quality. It was shown that perceived information literacy can enhance perceived ease of access to information. This is understandable, since the information literacy of an individual would reduce many of the perceived barriers in comprehending information, or identifying information sources according to their needs. Therefore, it could be assumed that young people’s perceived information literacy can ease access to and comprehension of information, thus creating a more positive disposition towards youth information and counselling services. Perceived reliability of information services is also affected by perceived information literacy. A plausible explanation could be that youth’s perceived information literacy skills allow them to be sure about the reliability of youth information and counselling services as sources of information. Ability to assess information sources and collected information critically may facilitate a quicker assessment of the reliability of the information source. We also found that young people’s perceived information literacy influences the perceived responsiveness of information services. This could be explained by the possibility that an individual with higher perceived information literacy skills is more likely to realise the effectiveness and responsiveness of information services. This result is similar to those of Shipman et al. ( 2009) and Chen ( 2015), where the authors found that a librarian-taught information literacy curriculum did raise awareness about the issue among the target group and increased the use of health resources and referrals to librarians for health information literacy support.

Regarding the multigroup analysis, the results showed some differences between the two groups (females vs. males) in terms of the prioritisation of factors comprising their perception of information services’ quality. This means that the emphasis on different constructs influencing perceived service quality can vary across genders. For instance, access to information was considered as a significant determinant by males when assessing the quality of information, whereas for females this path was nonsignificant. On the other hand, female respondents considered perceived information literacy as a significant determinant of perceived ease of access to information, whereas this path was nonsignificant for males.

To observe whether the variables (accessibility, reliability, responsiveness) mediate the relationship between perceived information literacy and perceived service quality, we carried out a mediation test. The test results showed that accessibility, reliability, and responsiveness of information services partially mediate this relationship. In other words, individuals’ perceived information literacy was found to have a significant indirect effect on perceived service quality. The results showed that a young individual with high perceived information literacy is more likely to have a positive perception of information services, given that the service provides easy access, reliable information, and is responsive to users. Possibly, with higher perceived information literacy, an individual is more capable of collecting, comprehending, evaluating, and using information. Therefore, when the service is equally easy to access, presents reliable information, and promptly responds to users’ information needs, an information literate young individual will possess a more positive perception of that information and counselling service.

Conclusions

This paper contributes theoretically to the literature on youth information behaviour and on information services development by providing evidence of the role of perceived information literacy in constructing the perception of youth information and counselling services. As the study results indicated, youth prefer easy and quick access to reliable information and information sources. Therefore, providing accurate and understandable information, and giving access to reliable information sources and channels, should be the central aim of the youth information and counselling services. This study indicates that enhancing the perceived information literacy of young people will help them to better assess the accessibility, reliability, and responsiveness of youth information and counselling services. This may result in more frequent use of these services. Moreover, the findings of this paper pave the path for future studies to conduct more in-depth research on the role of perceived information literacy in the assessment of different forms of information services. For instance, in future research, perceived information literacy could be considered as one of the constructs in the assessment of libraries’ service quality. This attempt itself is unique and paves the path for developing more user-centred information and counselling services for the youth.

Practical implications

This paper provides several insights and new knowledge to practitioners and workers in youth information services. For example, youth information and counselling agencies have to be quicker in responding to the information needs of young people. This study indicates the importance of responsiveness of information services, which determines the positive perception of youth towards the service. Therefore, along with easy access, the service must also focus on providing a prompt and empathetic response to youth’s information needs. By ensuring a stronger presence in both physical and virtual forms, these services can respond to the information needs of young people more promptly, and by introducing multiple channels, they can ensure a better and equal access to information for all.

From the study, it was evident that the youth place great emphasis on the accessibility, reliability, and responsiveness of youth information and counselling services, whilst constructing their perception of those services’ quality. Young people demand quick access to information and the commitment of information agencies to assist them in meeting their needs for reliable information. This suggests some measures that youth information and counselling services could take to meet their objectives.

Since responsiveness was given considerable importance by the youth, the agencies must focus on providing prompt information and counselling services related to the information areas that young people deem relevant and important. This could involve providing information about different topics, available through multiple channels, ranging from Websites to brochures and leaflets. Additionally, youth agencies’ workers should be trained to have the right mindset and attitude to assist the youth in a responsive and inclusive way. By enhancing perceived information literacy training, the agencies can improve workers’ attitudes and competencies according to the youth’s needs.

Along with responsiveness, easy access to different information domains is imperative to ensure a positive disposition towards information services. To provide such ease of access, youth information services can introduce multiple channels to contact and correspond with the youth. More interactive and responsive Websites could be designed, including virtual contact points. Mobile applications are gaining popularity, therefore, designing youth information applications might help the agencies reach a broader audience. In terms of physical presence, the agencies could increase the number of youth information and counselling centres; however, a more efficient choice would be to affiliate with educational institutions. This way, the other stakeholders could enhance students’ awareness and encourage them to use these services. Additionally, providing access through voice and video calls could allow more young people to join and use these services, even though they live far from the service centres. Finally, a strong presence in social media platforms is necessary to use those platforms as channels to correspond with the target group and keep it updated.

This study indicates the importance of not only improving youth information and counselling services, but also of improving the information literacy of the youth. Improving the perceived information literacy of young people will help them better assess the accessibility, reliability, and responsiveness of youth information and counselling services. This may result in more frequent use of these services. Educational institutions and youth agencies can design, or even codesign, information literacy programmes. In this heavily digitalised world, it is imperative that young people acquire and enhance their capacity to synthesise unfamiliar information, evaluate its authenticity, and use it to make informed decisions. Along with building this capacity, youth information services should focus on enhancing the major determinants of perceived quality by ensuring easier access through physical and virtual platforms, presenting reliable information in multiple forms and formats, and responding promptly to users’ information needs.

Limitations and future research

This paper has a few limitations that need to be addressed. First, the data used in this paper is part of a larger survey on everyday-life information behaviour of young people in Europe. Therefore, the entire dataset was not utilised in this research. The constructs that were used in this study to assess youth information and counselling services were matched with the major constructs used to measure perceived service quality of information services in the SERVQUAL model. However, since such measurement scales were not completely replicated while designing the survey, some of the constructs that were used in the SERVQUAL model were not included in the survey. Moreover, the items used to measure each construct were not identical to those used in the SERVQUAL model; thus, the items were tailored and slightly modified. For instance, perceived information literacy was measured in a limited manner, with only four items. However, the perceived information literacy questions focused on the ability to seek and evaluate information, which are the core aspects of the construct.

The collected data were partly skewed since the participants mostly came from Lithuania, Spain, and Portugal, even though the survey was administered in sixteen different countries. This limits the generalisability of the results for the entire European youth, since it would be necessary to take into account the cultural and social differences that influence the information behaviour of the youth. Finally, quantitative analyses often fail to account for the softer social and cultural aspects that largely influence information behaviour of young people. However, the study paves the way for future and more in-depth research. By incorporating regional differences, employment, education, and territorial and cultural factors as socio-demographic information, future studies could gain a deeper understanding of the role of the perceived information literacy of young people in assessing the quality of youth information and counselling agencies.

Acknowledgements

The survey on the information behaviour of youth in Europe was a part of Project Youth. Info: Future Youth Information Toolbox funded by the EU’s Erasmus+ programme. We want to especially acknowledge the European Youth Information and Counselling Agency (ERYICA) for distributing the survey throughout their networks.

About the authors

Muhaimin Karim is a Doctoral Researcher in the Department of Information Studies, Åbo Akademi. He has focused his research largely on information and media literacy, information behaviour, and information service design. His doctoral dissertation focuses on the information seeking behaviour and practices of the young population and designing youth centric information services. He can be contacted at muhaimin.karim@abo.fi

Shahrokh Nikou is a Docent of Information Systems and a senior lecture at the Department of Information Studies at Åbo Akademi University in Finland. His primary areas of research include information and knowledge management, literacy, digitalisation, digital platforms, and information practices. The contexts of his research ranges from higher education, creative economy, social media, and corporate and public organisations. He can be contacted at shahrokh.nikou@abo.fi

Gunilla Widén is Professor of Information Studies, Åbo Akademi University, Finland. Her research interests are in information and knowledge management, and information behaviour. She has led several large research projects focusing information culture, social capital theory, youth information, and information literacy. She can be contacted at gunilla.widen@abo.fi

References

Note: A link from the title is to an open access document. A link from the DOI is to the publisher's page for the document.

- Agosto, D. E. & Hughes-Hassell, S. (2005). People, places, and questions: an investigation of the everyday life information-seeking behaviours of urban young adults. Library & Information Science Research, 27(2), 141-163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2005.01.002.

- Association of College & Research Libraries. (2019). Framework for perceived information literacy for higher education. Association of College & Research Libraries. https://cse.google.com/cse.js?cx=001695639812020286035:rukhncex72e. (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3trgJhu)

- Bagozzi, R. P. & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74-94. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02723327.

- Batsleer, J. R. & Davies, B. (Eds.). (2010). What is youth work? Sage Publications.

- Beran, T. N. & Violato, C. (2010). Structural equation modelling in medical research: a primer. BMC Research Notes 3, Article number 267. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-3-267.

- Bloemer, J., de Ruyter, K. & Wetzels, M. (1999). Linking perceived service quality and service loyalty: a multi‐dimensional perspective. European Journal of Marketing, 33(11/12). 1082-1106. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090569910292285.

- Bowler, L., Julien, H. & Haddon, L. (2018). Exploring youth information-seeking behaviour and mobile technologies through a secondary analysis of qualitative data. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 50(3), 322-331. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000618769967.

- Bowler, L., Large, A. & Rejskind, G. (2001). Primary school students, information literacy and the Web. Education for Information, 19(3), 201-223. https://doi.org/10.3233/efi-2001-19302

- Chang, S., van Witteloostuijn, A. & Eden, L. (2010). From the editors: common method variance in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 41, 178–184. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.88.

- Chen, Y. H. (2015). Testing the impact of an information literacy course: undergraduates' perceptions and use of the university libraries' web portal. Library & Information Science Research, 37(3), 263-274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2015.04.002.

- De Oña, J., De Oña, R., Eboli, L. & Mazzulla, G. (2013). Perceived service quality in bus transit service: a structural equation approach. Transport Policy, 29, 219-226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2013.07.001.

- Dresang, E. T. (2005). Access: the information-seeking behaviour of youth in the digital environment. Library Trends, 54(2), 178-196. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2006.0015.

- Dresang, E. T. & Koh, K. (2009). Radical change theory, youth information behaviour, and school libraries. Library Trends, 58(1), 26-50. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.0.0070.

- Dryden, J. (2005). Do we care what users want? Evaluating user satisfaction and the LibQUAL+™ experience. Journal of Archival Organization, 2(4), 83-88. https://doi.org/10.1300/J201v02n04_06.

- Heath, C. F. & Cook, C. (2001). Users’ perceptions of library service quality: a LibQUALt qualitative study. Library Trends, 49(4), 548-583.

- Huang, E. (2009). The causes of youths' low news consumption and strategies for making youths happy news consumers. Convergence, 15(1), 105-122. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856508097021.

- Karim, M. & Widén, G. (2018). Future youth information and counselling: building on information needs and trends. European Youth Information and Counselling Agency. https://bit.ly/2Q0YwcQ. (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/33ww0Db)

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: a full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101.

- Koh, K. (2013). Adolescents' information‐creating behaviour embedded in digital media practice using scratch. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 64(9), 1826-1841. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22878.

- Landrum, H. & Prybutok, V. R. (2004). A service quality and success model for the information service industry. European Journal of Operational Research, 156(3), 628-642. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-2217(03)00125-5.

- Landrum, H., Zhang, X., Prybutok, V. & Peak, D. (2009). Measuring IS system service quality with SERVQUAL: users' perceptions of relative importance of the five SERVPERF dimensions. Informing Science, 12, 17-35. https://doi.org/10.28945/426. http://www.inform.nu/Articles/Vol12/ISJv12p017-035Landrum232.pdf. (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3ocQGtz) .

- Lee, H., Lee, Y., & Yoo, D. (2000). The determinants of perceived service quality and its relationship with satisfaction. Journal of Services Marketing. 14(3), 217-231. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040010327220.

- Markwei, E. & Rasmussen, E. (2015). Everyday life information-seeking behaviour of marginalized youth: a qualitative study of urban homeless youth in Ghana. International Information & Library Review, 47(1-2), 11-29. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572317.2015.1039425.

- Metzger, M. J., Flanagin, A. J., Markov, A., Grossman, R. & Bulger, M. (2015). Believing the unbelievable: understanding young people's information literacy beliefs and practices in the United States. Journal of Children and Media, 9(3), 325-348. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2015.1056817.

- Nikou, S., Brännback, M. & Widén, G. (2018). The impact of multidimensionality of literacy on the use of digital technology: digital immigrants and digital natives. In H. Li, Á. Pálsdóttir, R. Trill, R. Suomi, and Y. Amelina (Eds.) Well-Being in the Information Society. Fighting Inequalities, 7th International Conference, WIS 2018, Turku, Finland, August 27-29, 2018, Proceedings, (pp. 117-133). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97931-1_10

- Nikou, S., Brännback, M. & Widén, G. (2019). The impact of digitalization on literacy: digital immigrants vs. digital natives. In Proceedings of the 27th European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), Stockholm & Uppsala, Sweden, June 8-14, 2019. Association for Information Systems.

- Parasuraman, A., Berry, L. L. & Zeithaml, V. A. (1991). Refinement and reassessment of the SERVQUAL scale. Journal of Retailing, 67(4), 420.

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A. & Berry, L. L. (1988) SERVQUAL: a multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing, 64(1), 12-37.

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A. & Berry, L. L. (1985). A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. Journal of Marketing, 49(4), 41-50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298504900403.

- Pawluczuk, A., Hall, H., Webster, G. & Smith, C. (2019). Digital youth work: youth workers' balancing act between digital innovation and digital literacy insecurity. In Proceedings of ISIC, The Information Behaviour Conference, Krakow, Poland, 9-11 October: Part 2. Information Research, 24(1), paper isic1829. http://InformationR.net/ir/24-1/isic2018/isic1829.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76lXhI6CJ).

- Pedramnia, S., Modiramani, P. & Ghavami Ghanbarabadi, V. (2012). An analysis of service quality in academic libraries using LibQUAL scale: application oriented approach, a case study in Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (MUMS) libraries. Library Management, 33(3), 159-167. https://doi.org/10.1108/01435121211217144.

- Pitt, L. F., Watson, R. T. & Kavan, C. B. (1995). Service quality: a measure of information systems effectiveness. MIS Quarterly, 19(2), 173-187. https://doi.org/10.2307/249687.

- Prensky, M. (2001a). Digital natives, digital immigrants, part 2: do they really think differently? On the Horizon, 9(6), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1108/10748120110424843.

- Prensky, M. (2001b). Digital natives, digital immigrants. On the Horizon,9(5), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1108/10748120110424843

- Qayyum, A. & Williamson, K. (2014). The online information experiences of news-seeking young adults. Information Research, 19(2) paper 615. http://InformationR.net/ir/19-2/paper615.html. (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3uwU5FG)

- Robinson, J. (2010, June 17). UK and US see heaviest newspaper circulation declines. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/media/2010/jun/17/newspaper-circulation-oecd-report (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/33H3b7f)

- Rowlands, I., Nicholas, D., Williams, P., Huntington, P., Fieldhouse, M., Gunter, B., Withey, R., Jamali, H., Dobrowolski, T. & Tenopir, C. (2008). The Google generation: the information behaviour of the researcher of the future. Aslib Proceedings, 604), 290-310. https://doi.org/10.1108/00012530810887953.

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Smith, D., Reams, R. & Hair, J. F. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): a useful tool for family business researchers. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 5(1), 105-115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2014.01.002.

- Saurina, C. & Coenders, G. (2002). Predicting overall service quality: a structural equation modelling approach. In A. Ferligoj & A. Vrar (Eds.), Developments in social science methodology, vol. 18 (p. 217-238). Faculty of Social Sciences - University of Ljubljana. https://bit.ly/3vWrlGz.

- Schwartz, M. (2005). Newspaper circulation woes offset by Internet gains. NAA says publishers should focus on audience reach rather than number of newspapers sold. B to B, 90(16), 3.

- Shenton, A. K. & Dixon, P. (2003). Just what do they want? What do they need? A study of the informational needs of children. Children and Libraries, 1(2), 36-42. https://doi.org/10.5860/cal.1n2.

- Shipman, J. P., Kurtz-Rossi, S., & Funk, C. J. (2009). The health information literacy research project. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 97(4), 293–301. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.97.4.014

- Subhash, R. B., Krishnamurthy, M. & Asundi, A.Y. (2018). Information use, user, user needs and seeking behaviour: a review. DESIDOC Journal of Library & Information Technology, 38(2), 82. https://doi.org/10.14429/djlit.38.2.12098.

- Subrahmanyam, K. & Smahel, D. (2010). Digital youth: the role of media in development. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Wilson, T. D. (2000). Human information behaviour. Informing science, 3(2), 49-56. https://doi.org/10.28945/576.

How to cite this paper

Appendices

Appendix A: List of the items and sources

| Constructs | Definition |

|---|---|

| Accessibility | Please rate how difficult or easy it is to access information in your everyday life on the following topics (1=difficult to access, 5=easy to access) |

| Education and training (how to choose school, how to select a course, manage issues in school, etc.). | |

| Health and wellbeing (how to protect your physical and psychological health, health related advice, etc.). | |

| Leisure time (how to spend free time, meet new friends, youth clubs and activities, sports, etc.). | |

| International mobility (how to take part in international projects, study, volunteer or work abroad, etc.). | |

| Volunteering (how to take part in a youth project or youth organisation, how to get active in helping others, etc.). | |

| Perceived information literacy | How do you evaluate the information received? |

| I am able to identify what type of information source I need for different information needs. | |

| I am able to evaluate the scope and content of the chosen resources. | |

| I can examine and compare information from various sources in order to evaluate reliability, validity, accuracy, authority, timeliness, or bias. | |

| I can identify sources with alternative viewpoints to provide context and balance. | |

| Reliability | In your opinion, how reliable is the information received from? (1 - not reliable at all, to 5 - very reliable). |

| Youth information and counselling services. | |

| Youth club or youth organization. | |

| Youth worker at the public administration office. | |

| Counsellor or teacher at school or university. | |

| Internet social media (chatting, forum, online communities, Facebook). | |

| Responsiveness | In your experience, how do the youth information and counselling services help you in sorting out problems in the following areas of your life? (1=not at all, 5=helped a lot). |

| Education and training. | |

| Employment, internships, apprenticeship. | |

| Leisure time/free time. | |

| International mobility. | |

| Perceived service quality | Please say if you agree with the following statements. |

| If I ever need to look for work, I am sure I can receive support from the youth information and counselling services. | |

| I would recommend to my friends that they use the youth information and counselling services. | |

| When I started to use youth information and counselling services, I am sure I can always get the required information. | |

| I am very satisfied with the information I received from the youth information and counselling services. | |

| When I started to use youth information and counselling services, my life changed for better. |

Appendix B: Country of residence and sex distribution

| Country of residence | Sex | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Other | Total | |

| Austria | 13 | 45 | 1 | 59 |

| Belgium | 11 | 40 | 0 | 51 |

| Croatia | 1 | 10 | 0 | 11 |

| Estonia | 1 | 11 | 0 | 12 |

| Finland | 11 | 43 | 2 | 56 |

| France | 9 | 18 | 0 | 27 |

| Germany | 16 | 37 | 2 | 55 |

| Ireland | 31 | 34 | 1 | 66 |

| Latvia | 19 | 70 | 0 | 89 |

| Lithuania | 464 | 879 | 21 | 1364 |

| Luxembourg | 63 | 76 | 1 | 140 |

| Macedonia | 9 | 21 | 0 | 30 |

| Norway | 3 | 11 | 0 | 14 |

| Portugal | 328 | 339 | 12 | 679 |

| Spain | 202 | 346 | 4 | 552 |

| Ukraine | 24 | 56 | 2 | 82 |

| Total | 1205 | 2036 | 46 | 3287 |