Resident university students’ everyday-life information seeking behaviour in Pakistan

Muhammad Asif Naveed, Syeda Hina Batool, and Mumtaz Ali Anwar

Introduction. This study seeks to investigate the everyday-life information seeking behaviour of postgraduate students living in the residence halls of the University of the Punjab, Lahore.

Method. A critical incident technique, a qualitative research approach, was used in order to achieve its objectives. Face to face interviews of twenty postgraduate students, having a rural background, selected through purposive sampling, using a semi-structured interview approach were conducted.

Analysis. The verbal data was organized and analysed using thematic analysis. The important data was coded and grouped for deriving themes.

Results. The participants' situations were centred on health, socio-economic, cultural, technological, and legal issues. These students mainly relied on inter-personal information sources in order to resolve their everyday-life issues. The role of university libraries was non-existent in meeting the everyday-life information needs of these participants. Some participants suspected the quality and scope of information received from news and social media. These participants were mostly unsuccessful in accessing needed everyday-life information on time due to lack of information sources.

Conclusions. The results have implications for both theory and practice. It extends the scope of the everyday-life information seeking model by adding a new dimension and provides insights into trans-national perspectives. If the everyday-life issues of resident postgraduate university students remained unresolved due to lack of information and institutional support, it might affect their academic achievement and research productivity. Therefore, the university administration should plan on-campus consultancy services within student affairs offices for supporting such students to overcome difficulties in light of their everyday-life information needs. The library staff should also design services to support those provided by the university administration.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper901

Introduction

It is highly desirable, logical, and fundamental to understand people's information behaviour before developing need-based information resources and designing high quality information services for them. This perception has resulted in a good amount of library and information science research that deals with the information seeking behaviour of individuals and groups from different contexts such as academia, workplace and everyday-life. A number of studies have focused on work, health and academic purposes (Koo and Gross, 2009; Mehra and Bilal, 2008). However, there has not been a great deal of work in this area in the field of librarianship (Agosto and Hughes-Hassell, 2005; Sin and Kim, 2013; Williamson, et al., 2012). Research highlighting personal motivations and views can identify real patterns of information use. Furthermore, identification of the patterns in interpersonal information exchange would enable practitioners to design need-based information delivery services. Researchers have broken the boundaries of classroom and libraries to study information behaviour (Davenport, 2010) and investigated various groups such as children (Meyers et al., 2007; 2009), urban young adults (Agosto and Hughes-Hassell, 2005; Williamson et al., 2012) and international students (Sin and Kim, 2013).

It appears that only a few studies have been conducted so far examining the everyday-life information seeking practices of students moving from rural areas to large cities (Rafiq et al., 2021). A great number of individuals from rural areas move to big cities for better socio-economic opportunities and higher education in developing countries having large rural populations (World Migration Report, 2018). In Pakistan, a significant number of students come to famous universities from a wide geographical area lacking access to higher education. Villages in the rural areas of Pakistan usually comprise of 1000 to 3000 persons with limited facilities available and poor information infrastructure (Naveed et al., 2012; Naveed and Anwar, 2013, 2014).

Rural inhabitants normally have a limited exposure to large city life, which is totally different from the rural contexts, and making an adjustment in the urban context is not easy for them. These rural students, while residing in university residence halls, have to encounter a number of new situations in their daily lives and face problems in making adjustments to the new situations (Hassan and Raza, 2009, 2013). The limited exposure and socio-demographic knowledge of these rural students do not support them in problem solving in the newly experienced, urban life-world. Only a few studies have investigated students' everyday-life information seeking behaviour focusing on their academic activities (Sin and Kim, 2013). However, their everyday-life information seeking experiences during their stay in larger cities should also be of interest to library and information science professionals. This is an important topic that has not received due attention so far.

In view of the above, this study explores everyday-life information seeking practices of postgraduate students who come from rural areas and reside in the university hostels facing many problems for adjustment and survival. The present study (based specifically on the South Asian context) highlights students' information source horizon (Sonnenwald, 1999), their everyday-life issues and source preference criteria. The mapping into Savolainen's (2007) developed framework presents a detailed overview of participants' information behaviour (primary, secondary and marginal issues of interest and important and less important information sources), common and diverse results and social and cultural differences. Also, to complement the participants' information source horizon, the present study expanded and added the participants' satisfaction levels with the consulted sources and highlighted their issues while engaged in information seeking.

This research also responds to a gap in the literature by exploring the everyday-life information seeking of postgraduate resident university students with rural background. It also aims to highlight these students' problems that they face during their information encounters which will identify their preferences and special information needs. Its findings, it is hoped, will provide significant guidance while designing and delivering information services for these students which will have direct implications for higher education authorities providing information services, such as libraries, information commons, or library resource centres.

Literature review

There is a reasonable body of literature on everyday-life information seeking . Several terms have been used for the concept over time; for example, non-work information seeking, citizens' information seeking, non-research seeking, and non-school seeking (Agosto and Hughes-Hassell, 2005). Information seeking of this kind has been investigated among individuals and groups working in different sectors (e.g., investors, historians, grocery shoppers). Similarly, a number of studies have investigated students (Agosto and Hughes-Hassell, 2005; Meyers et al., 2009; Williamson et al., 2012). Some of this literature has focused on the role of the Internet, news, and social media in the information behaviour of students (Agosto and Hughes-Hassell, 2005; Savolainen and Kari, 2004; and Williamson et al., 2012). A number of studies focused theoretically on everyday-life information seeking (Given, 2002; Savolainen, 2007; Davenport, 2010) while some have argued that qualitative research methods should be employed (Bates, 2004).

More broadly, Savolainen (2007) discussed two approaches to everyday-life information seeking: seeking orienting information and seeking problem-specific information. The problem-solving information refers to information needed for solving a problem or completing a task whereas the orienting information relates to information about everyday events. In library and information science, a small number of studies are focused on seeking orienting information as compared to seeking needed information. The studies that focused on seeking orienting information found that print media, broadcast media, and human resources were the most frequently used information sources (e.g. Savolainen, 1995; 2007; Williamson, 1998; Williamson et al., 2012). The present study has focused on both approaches.

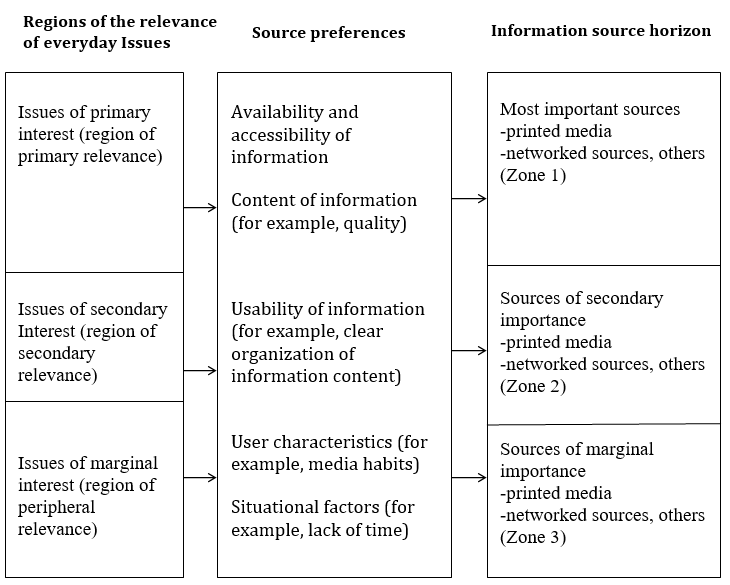

Savolainen (2007) developed a framework by combining concepts of regions of relevance (Schutz and Luckmann, 1973) and information source horizon (Sonnenwald, 1999), and added a third component of source preference criteria to examine the seeking of orienting information of environmental activists (Figure 1). According to Schutz and Luckman, there are four major regions of relevance: the world within our reach is the primary region of relevance, the world within our potential reach is the second region of relevance, relatively irrelevant regions, and irrelevant regions. They were of the view that people structure their everyday-life based on their interests. Sonnenwald introduced the concept of an information horizon that can consist of a variety of information sources with which all of us can interact.

Savolainen (1995) approached everyday-life information seeking more broadly and argued that work and non-work (job related) information seeking overlapped and could not be separated. He further stressed that everyday information seeking could not be understood in isolation, but should be examined within the context of the actual work and activities. He was of the view that work-related information seeking and everyday-life information seeking overlap and one should not create this false dichotomy. While examining undergraduates' information seeking, Given (2002 ) reported overlap between academic and everyday information needs (for example orientation and games allowed them to socialise). The study explored the lives of twenty-five students at one Canadian university through qualitative interviews in the light of Savolainen's framework (1995). The findings revealed the information seeking behaviour of students before and after admission. The interviewees found that on-campus interpersonal information sources (peers) were accessible and reliable. The study concluded that students' everyday experiences also informed their academic activities (students' chosen assignment topics related to their part-time occupation), which reinforced Savolainen's framework.

In contrast, Davenport (2010) approached everyday-life information seeking in non-work contexts, which included individual's cultural and social factors that impacted on the process of acquiring information. Similarly, Carey et al. (2001) advised everyday-life information seeking researchers to change focus from individual studies to broader cultural settings. In contrast to work environments, everyday lives can be considered less bounded by various tasks and roles (Davenport, 2010). A number of studies brought insights on students' library usage patterns, academic needs, their preferred sources of information, and the factors involved in the choice of information sources, however, their everyday-life information seeking needs have been rarely investigated (Sin, 2015). The studies related to the everyday-life information seeking practices of students will be discussed in the following sections.

Mehra and Bilal (2008) examined the information needs and seeking behaviour of international students while using information technologies. The mixed-method approach was used to collect data from ten Asian graduates who were studying in the United States. The top three information needs identified by the researchers were: the need to know US academic programmes, the day-to-day local information, and knowing about US culture and customs. While encountering information, these students were mainly challenged by poor searching skills, the non-availability of multiple language interfaces, and information overload.

The new immigrant adolescent students' everyday-life information seeking when they were isolated from their peer groups was investigated by Koo and Gross (2009). Data were collected from a purposive sample of 10- to 20-years old, immigrant adolescents. Their top three everyday-life information needs were: English language skills, social skills, and study skills to score high in studies. The researchers found that these students' main source was their family members, generally parents.

A mixed-method approach was used by Nkomo et al. (2011) to investigate the Web information seeking behaviour of students and staff of both urban and rural-based universities in South Africa. The main data collection instrument was a questionnaire which was followed by limited interviews. Both groups of participants perceived the Web to be the most beneficial information source. However, these participants utilised only a few Web channels. Sin and Kim (2013) studied the everyday information seeking behaviour of international students. They found that the use of social networking sites, like Facebook, was significant. The top five information needs of these students were: finance, health, news of their country, housing, and entertainment. The participants showed their satisfaction regarding information obtained through social networking sites.

Williamson et al. (2012) conducted a qualitative study using interviews and a series of tasks involving thirty-four young-adult university students. The results showed that the print news media were a popular source of information among these students. However, social media were a good source to communicate with friends. They also found that these students' everyday-life information seeking involved seeking information about suicide statistics, buying products, rental properties, jobs, movies, death notices, travel and finance. These students felt that online material lacked credibility due to the editable features of Websites. The participants also experienced accidental information acquisition during their everyday-life information seeking. They shared multiple examples as they encountered information regarding health, movies, and financial planning.

The everyday-life information-seeking behaviour of twenty-seven urban teens (aged 14-17) was investigated by Agosto and Hughes-Hassell (2005). They used multiple data collection techniques which included surveys, written activity blogs, audio journals, photographic tours, and group interviews. The most preferred everyday-life information seeking source for these young people was friends and family, especially their peers. However, the most unwanted source for everyday-life information seeking was librarians and libraries. Koo and Gross (2009) also found that peers were the favourite and most valuable source of everyday-life information seeking information for the immigrant adolescents. Loan (2011), who conducted a study of rural college students, found that their frequency in using the Internet was less than urban students and that they mostly used it for educational purposes. A survey of 112 international students also revealed that the Internet, family, and friends were the main sources of their everyday-life information seeking. These students faced the challenges of findings legal and financial information. Similarly, these students mentioned that they found difficulty in finding credible and relevant information (Sin, 2015).

The literature reviewed above shows that some research has been conducted on the everyday-life information seeking behaviour of students in general. The way the students coming from rural areas cope with their life in big cities has not received due attention. Previous studies mainly identified the participants' information needs and preferred information sources. However, Savolainen (2007) expanded everyday-life information seeking approach and combined regions of relevance with information source horizon. Therefore, the present study was designed to fill the literature gap in the light of Savolainen's developed framework (Figure 1). It would be interesting to know the everyday-life information seeking behaviour of resident, postgraduate university students with rural backgrounds during their stay in larger cities. The mapping into Savolainen's (2007) framework (Figure 1) will highlight these students' regions of relevance and information source horizon, as this study followed his approach to everyday-life information seeking. This study will also contribute theoretically by expanding and adding participants' satisfaction levels (highly satisfied, satisfied, and marginal) with the consulted sources.

Theoretical framework and method

The purpose of this research was to examine the everyday-life information practices of postgraduate students with a rural background in the light of framework developed by Savolainen (Figure 1). The qualitative research approach, the critical incident technique, was used to determine why and how these students look for everyday-life information because it is an appropriate and effective technique to explore participants' immediate past which aimed at detecting critical incidents of human behaviour about particular phenomena (Ikoja-Odongo, 2002). According to Flanagan (1954, p. 327), it is 'a set of procedures for collecting direct observations of human behaviour in such a way as to facilitate their potential usefulness in solving practical problems'. In this technique, the participants are asked to think of and identify such critical incidents or situations in the past month or two that forced them to look for information (Butterfield et al., 2005; Byrne, 2001; FitzGerald et al., 2008).

Critical incident technique was an adequate choice as this research seeks to explore critical incidents forcing rural students living in the university residence halls looking for everyday-life information. In addition, this technique had also been successfully used to explore participants' critical incident related human information behaviour by Ikoja-Odongo, (2002), Mooko (2005), Zaverdinos-Kockott (2004) and Naveed 2016). The participants were asked to describe the most significant and marginal incidents, in which they had to make a decision, find an answer to a question, solve a problem or try to understand something that forced them to look for everyday-life information.

This study conceptualised everyday-life experiences in a broader (social) perspective which believes that work and non-work activities cannot be separated fully but overlap (Savolainen, 1995) and used Savolainen's expanded framework (2007) to explore resident university students' everyday-life information seeking practices who had a rural background. Furthermore, it examined the concept of information practice using a social approach rather than cognitive and affective approaches to understand it holistically and naturalistically. According to Pettigrew et al. (2001), social approach to information seeking focuses on 'the meanings and values associated with social, socio-cultural, and sociolinguistic aspects of information behaviour; studies based on social frameworks tend to employ naturalistic approaches, which have gained popularity within information behaviour in general' (p. 54). There are a number of researchers, proponents of the social approach to information behaviour, who suggested the use of the term information practice rather than information behaviour (McKenzie, 2003; Fulton and Henefer, 2010; Savolainen, 2007, 2008). It must be noted, of course, that this opinion is not universal and that much research using the term information behaviour has explored the social factors influencing such behaviour, for example, Alwis et al., (2006), Loudon et al., (2016), Okocha, (1995), Tury (2015), and Zhu and Liao (2020).

This research is concerned with non-work information seeking: the work-related information seeking of these students is beyond the scope of this study. The Savolainen framework is significant in gaining an understanding of individuals' everyday information seeking activities and provides a more structured way to present information seeking findings (Given, 2002). By utilising the critical incident technique, it is considered that everyday-life information seeking experiences are mutually constructed with the interaction of work and non-work environments influenced by certain aspects and cannot be studied in isolation.

This exploratory study addressed the following research questions:

- 1). What type of incidents do the resident postgraduate students with rural backgrounds encounter which force them to seek everyday-life information?

- 2). What sources do these students use for seeking everyday-life information?

- 3). What preference criteria do these students use while selecting information sources?

- 4). How satisfied are these students with the information sources that they consult?

- 5). What barriers do they face in everyday-life information seeking?

Since qualitative research values the perspective and background of the researcher, it is worth mentioning here that two of the present researchers had rural backgrounds and school education in the rural setting and then moved to the big city for higher education. They personally experienced this phenomenon. The third researcher, a female with an urban background, was thoroughly briefed on such issues by the other two researchers so that an in-depth exploration of the proposed phenomenon might be done.

Research process

Population, sampling and data collection

All the postgraduate students of the University of the Punjab having rural background and residing in the hostels were the population of this study. Due to the exploratory nature of the study, the interviewees were selected using a purposive sampling technique. The selection of participants was based on their rural background, university residence, and minimum one-year residential period. It was easy to identify such participants as one of the researchers himself who had a rural background was living in the university hostel. Face-to-face interviews (35-40 minutes long) of twenty postgraduate students using a semi-structured interview guide (Appendix A) were conducted by visiting their hostels with written permission from the concerned authorities. The participation of interviewees in the interview was on a voluntary basis and they had the freedom to decline to participate at any stage. The authors were confident that the students were fully supportive of the research and did not feel any risk of criticism or adverse consequences in case of declining survey participation.

Before data collection, the participants were informed about the research purpose and value of their participation in the study. The attitude of these students to take part in the survey was positive as they became convinced about the significance of their role in the study and happily gave their consent as participants. These participants were also assured about the confidentiality and anonymity of data. This university does not require any approval concerning ethics for researching with students. The interview questions were read out to the participants and their responses were audio recorded. Follow up questions not necessarily on the interview guide were also asked. Each participant was debriefed at the end of the interview for clarification, verification, and authentication. The interview data were then transcribed.

During the interviews, the participants were also asked about their primary, secondary, and marginal issues of everyday interest as depicted in Figure 1 (column 1). Their information source horizons were developed based on their verbal responses. They were asked about the most significant sources (Zone 1), somewhat significant (Zone 2), and marginal sources (Zone 3) (column 3). As Savolainen expanded his framework by adding source preference criteria (Figure 1), participants were also asked about their preference criteria for information sources (column 2).

The research questions 4 and 5 were used to establish the respondents' satisfaction level and barriers while encountering everyday-life information seeking. These questions complement the information source horizon of the participants. The satisfaction level results expand Savolainen's (2007) model. These results will be divided into three zones to expand the framework. The respondents are asked about their highly satisfied consulted sources (Zone 1), satisfied sources (Zone 2), and marginally satisfied sources (Zone 3). The last research question highlights the respondents' issues/barriers while seeking everyday information and informs stakeholders to examine their policies and procedures.

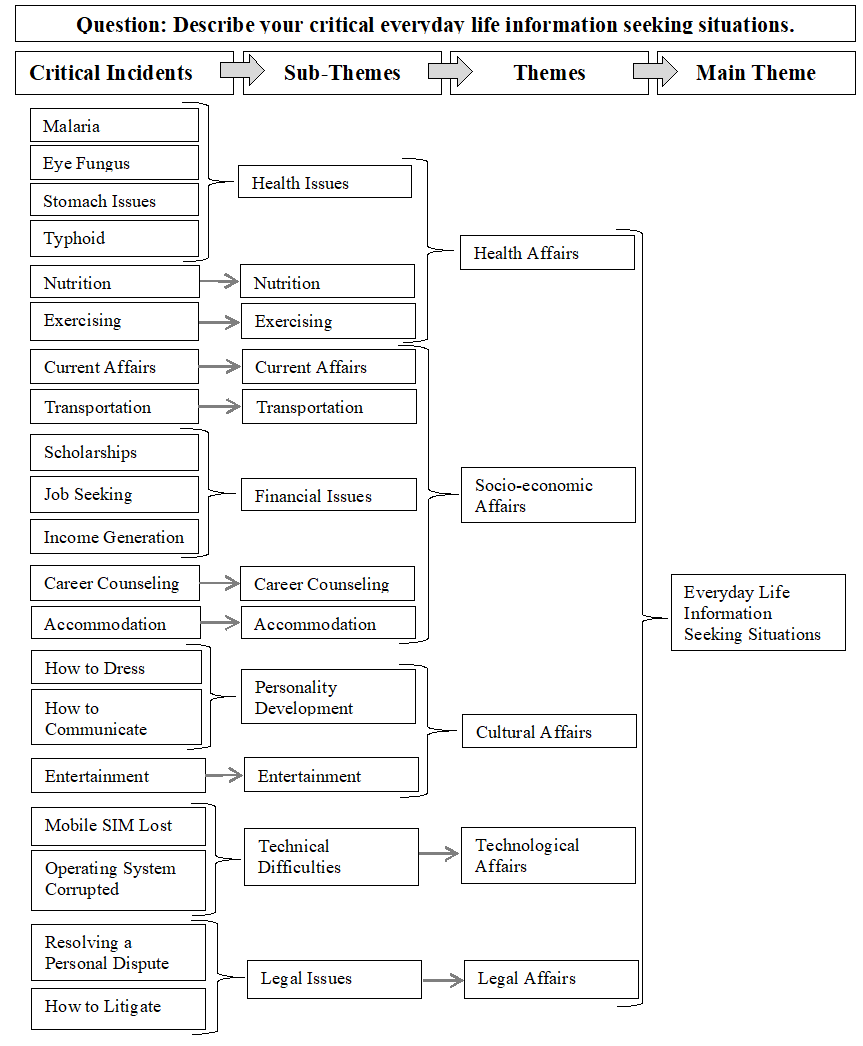

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was used for data analysis as it allows the researcher to identify, analyse, and interpret patterns of meanings in large qualitative data sets by sorting them into broader themes (Braun and Clarke, 2012; Maguire and Delahunt, 2017). The interview transcripts were read and reread carefully in order to discover themes in the data by marking the underlying concepts and their occurrence. The multiple responses were grouped together and reduced into everyday-life information seeking situations and information sources using a six-step approach (e.g., familiarisation, coding, theme generation, review, naming, and write up) used by Braun and Clarke (2012). It attempted to illuminate various hidden contextual meanings related to everyday-life information seeking situations (Figure 2).

The related meanings or codes were later clustered and grouped in order to develop broader themes. The development of broader themes was dependent on everyday-life critical information situations. For instance, if someone mentioned a disease-specific situation that forced one to look for information, such a situation was grouped in the theme of health issues. In the same way, if a participant mentioned an incident related to job seeking or income generation, such a situation was grouped under the broader theme of financial issues. All these broader themes were used to develop main themes such as information seeking situations. The transcribed data were continuously read and compared for theme identification related to each research question to describe the whole phenomenon (information seeking situations, information sources, reasons for selecting information sources, satisfaction or dissatisfaction and barriers). The verbatim responses have been added where felt necessary. It should be noted that since this study examined the experiences of only twenty participants, it cannot claim to be the voice of all postgraduate students of the university with a rural background.

Results and discussion

Demographic composition of the sample

Of the twenty participants, ten were males and ten females, with eleven MPhil and nine PhD students. Lahore, the second biggest city of Pakistan and a hub of many public and private universities, was the research site. Nine students were from northern Punjab, four of southern Punjab, six from central Punjab and one was from Azad Jammu and Kashmir. These participants had a varied residence period with a minimum of one to a maximum of six years. The age of these participants varied within the range of 22 to 32 years.

Everyday-life information seeking situations and incidents

A closer look at the data analysis indicated that a majority of the participants sought information to solve problem-specific issues (e.g., health, transportation) rather than orienting information (e.g., current affairs, scholarships) (Savolainen, 2007). This evidence identified participants' information behaviour towards problem solving information seeking rather than habitual information seeking for example reading newspapers or magazines, watching television etc. (Savolainen, 2007). The findings show a variety of critical incidents (Figure 2) that led participants to seek everyday-life information. These incidences ranked according to the frequency of their appearance in the participants' verbatim.

A majority of the participants mentioned that the most significant health related issues were centred on fever, typhoid, eye-fungus, body pain, allergy, eczema, diarrhoea, and other stomach issues. For instance, several students described the issues as: 'my stomach issues forced me to find information on diet management' (Participant 1) and I had stomach issues due to impure diet from hostel canteens' (Participant 7). Another participant (P3) described 'I don't know what to eat for good health while living at the university hostel'. Some participants mentioned their seasonal infections such as 'eye fungus', 'malaria', and 'typhoid' as their health-related information seeking situations. One student (P11) expressed his experience as, 'I had been infected by severe allergy resulting from an insect bite.' These issues were followed by socio-economic affairs such as transportation, accommodation, current affairs, job seeking, scholarships, income generation, career counseling, and accommodation. It is worth mentioning that a majority of the male students was especially concerned with information related to nutrition (what to eat while living at the hostel), which was followed by income-generation (home tuition and part-time jobs) and job-seeking. The male students mentioned that their information seeking issues (income-generation and job-seeking) were the result of Pakistani culture as males had to be financially independent earlier than females and were generally expected to partially bear their higher education expenses.

A number of students, particularly females, expressed cultural information needs. For example, they wanted to know what to wear, how to dress up on different occasions (welcome and farewell parties, annual dinners, and sports days), and entertainment. These females appeared more oriented towards social and cultural information needs than males. However, it is worth mentioning that the way in which these students are brought up and the background of their families and their socio-economic status also influences the patterns of their information needs. For example, one male participant stated, 'I did not need information regarding dressing as I used to go to various socio-political parties in big cities and I can easily decide which dress I need to wear based on the requirement of each gathering'. The results also suggested that information pertaining to technological (e.g., operating systems corrupted, sim card lost, etc.) and legal issues (e.g., resolving personal disputes, how to litigate if needed, etc.) were of less concern to these participants as only a few participants mentioned such critical incidents.

Several previous studies have found that everyday-life information seeking of international and immigrant adolescent students involved important personal issues related to health, finance, social, cultural and housing decisions (Mehra and Bilal, 2008; Koo and Gross, 2009; Sin and Kim, 2013). Similarly, the present study revealed that resident postgraduate students' top everyday-life information seeking issues were health, finance, transportation, and accommodation. This study also found that these respondents sought information more for problem-related issues than for orienting information.

Sources of everyday-life information

The participants were asked about the information sources that they used to manage important issues related to their day-to-day concerns. Most of the respondents used several sources whereas a few did nothing about the issues that they faced. These non-seeking informants were probed as to why they didn't seek information. One participant said: 'I couldn't do anything about it' (P3) while two did not know about 'where to get advice' (P4 and P7). Some participants did not seek information because they were not sure about where to get advice from. It could also mean that those issues were not very serious and did not disturb their daily routine.

The participants who tackled the issues were asked about the sources of information they normally consulted and considered most important, important or less important. The most used information source was informal social networks such as class or hostel fellows and friends. Both male and female participants rated people very high as the information source for seeking everyday-life information. Some participants used the Internet to find everyday-life information related to health, current affairs, entertainment, scholarships, and transportation as they could conveniently obtain information from this source. The sources used on the Internet were: social media (Facebook and Twitter), online newspapers, Websites of different news channels, Google Maps, etc. They also used social media as a source of information on current and public affairs. In addition, the informants mentioned newspapers and television as the least consulted information sources. These findings reflect participants' seeking orienting information through the Internet. It can be concluded that the Internet replaced print sources and some respondents used this source for everyday orienting information. They also consulted the university health unit and nearby hospitals in solving their health-related problems.

It is interesting to mention that the use of news media such as television and newspapers was embarrassing for some participants. Their view was that these information sources caused frustration. A female student said, 'I don't need to use news media as current circumstances of the country as well as world cause tension and frustration' (P15). A female doctoral student pointedly stated that 'I am fed up; I am not concerned [with] this bullshit... I am very sensitive, I cannot bear news, violence, I have some psychological issues, I used to suffer after watching or reading, so I avoid this' (P12). Another female doctoral student shared her viewpoint as:

I avoid reading a newspaper as it is a big source of high blood pressure. It causes me depression and anxiety. Although it is a source of information, I get disturbed for the whole day as we cannot do anything for our country and our leaders build their own empires, all are corrupt, we cannot trust them (P17).

The above stated behaviour of respondents could be the main reason for their lesser seeking of orienting information. It is also interesting to mention here that the role of media in reporting violence these days reduced seeking of orienting information by these respondents. It seems that social factors, for example, political conditions, the role of media can influence information seeking of students.

The role of the university libraries (both central and departmental) sourcing everyday-life information was almost non-existent in these findings. A few students mentioned the reasons for not using the library for everyday-life information. One participant was of the view that 'bookish knowledge didn't fulfill my needs' (P13). He further argued that 'I require workable and practical information and the library didn't help us for such information'. Another student mentioned: 'I don't find everyday information from the library'. A few students perceived that the library was not a suitable place for seeking everyday-life information. The following statements provide this evidence: 'We don't need to go to the library for everyday information because it is hectic and wastage of time' and 'library is not managed properly.'

The role of the University Health Centre in disseminating health information was perceived as poor by a couple of participants. One respondent mentioned that 'my experience with the Health Centre was very bad because my fever turned into typhoid' (P8). The other said that 'I was suffering from eye fungus and my situation got worse due to improper diagnosis of the Health Centre' (P4).

Reasons for selecting information sources

What criteria did the participants use for selecting everyday-life information sources? A large majority of these students selected the sources of information due to their availability, ease of use, and convenience. Some participants selected information sources because they were interactive, reliable, and provided timely information. Only a couple of the participants mentioned authenticity as a criterion for selecting an information source indicating the 'cost-benefit ratio' framework while seeking everyday information.

Three participants said that they selected from whatever sources were available because they did not have any other option. It is evident that these respondents did not have many information sources to consult as one participant (P9) stated that 'What can I do in the absence of other information sources?' Another one was of the view that 'I'm satisfied [with] whatever I have available because I don't have any other option' (P6). This is an indication that these participants had to make compromises while selecting sources of information because they had no other option available to them. Their overwhelming reliance on people in seeking everyday-life information might be the result of this compromise.

These participants selected information sources on the basis of their availability and convenience which confirms the findings of Savolainen (2008) and Connaway et al. (2011). It also indicated that the 'principle of least effort' as a decisive factor in participants' selection criteria for everyday-life information sources rather than the 'cost-benefit ratio'. The first focused on the accessibility of the channel and the second on the quality of the information provided by the channel (Bronstein and Baruchson-Arbib, 2008). In addition, the premise of the principle of least effort, in the information seeking context, is that individuals adopt a course of action, in performing information seeking tasks, which will use the least probable average of their work time - the least effort. It also predicts that an information seeking client 'will minimize the effort required to obtain information, even if it means accepting lower quality and quantity of information' (Case, 2005, p. 291).

Satisfaction with information sources used

Were these participants satisfied with the information sources that they used? A majority of them felt that they were highly satisfied with human information sources such as friends, classmates, hostel fellows, seniors, and teachers because they perceived that the information they received from these sources was reliable and relevant. For instance, one male participant described his satisfaction as 'I am satisfied with friends and classmates because they always give accurate and relevant information' (P8). Another argued that 'I am satisfied with the information that I got from my friends because my information needs were fulfilled' (P16). Another shared his experiences as, 'I 'm satisfied all the time with friends, classmates, and hostel fellows because they provided timely information whenever consulted ' (P10). However, a few participants were dissatisfied with these sources as they argued that these sources could not guide them in an appropriate way like specialists and also because information from these sources was not always relevant and timely.

The above findings related to the information channels used and reasons for using those channels for everyday-life information seeking confirm those of previous studies (Agosto and Hughes-Hassell, 2005; Koo and Gross, 2009; Savolainen, 2008; Williamson, 1998). A majority of the respondents of the present study, as those of the ones cited above, ranked human sources very high for everyday-life information seeking.

The results of the present study reinforce Savolainen's (1995) approach to everyday-life information seeking that work (academic) and non-work (everyday) issues cannot be studied in isolation as the participants of this study mainly rely on their class and hostel fellows to solve their everyday issues (health, finance, accommodation etc.). They also consulted the university health unit primarily to solve their health issues. These findings support Savolainen's (1995) approach to everyday-life information seeking that the everyday information seeking overlaps with academic information sources.

On the other hand, most of these students were marginally satisfied with news media as they were of the view that these sources broadcast diluted and falsified information. Some of the participants believe that the news channels did not deliver accurate, reliable, and objective information and sometimes these channels broadcast even misinformation. For instance, one participant expressed his dissatisfaction as, 'I'm unhappy with media sources, news channels and newspapers, etc. because they are biased, have their own interests and did not reveal true information ' (P2). Similarly, another three students shared their views as:

I am dissatisfied with international media sources such as CNN, BBC, etc. because they are biased and compromise objectivity and have their own interests and did not reveal the true picture. Also, the local news channels like Geo, Express News, ARY, etc., follow their footprints and broadcast controlled information and sometimes even misinformation (P8).

I'm dissatisfied with the information that I had from media sources because they broadcast subjective information. We have to verify information from multiple information sources. Only after verifying information we believe in it. I am also dissatisfied with the social media because most of the time people share information which is untrue (P5).

I avoid news media because it is biased and compromises objectivity. It has its own interest and didn't reveal true picture. Also, it broadcast controlled information and sometime even misinformation (P9).

It is interesting to mention here that misinformation causes mistrust among some respondents. These mostly approachable sources (media, social media) are also sources of distrust among these participants. Despite marginal satisfaction with the news media channels some participants were of the view that they were satisfied because they verified information themselves by using multiple information sources. For instance, one student argued that ' every source has different dimensions so cannot find all information from one source, you have to consult different sources' (P8). Another one stated, 'I 'm satisfied because I myself verify information from different information channels ' (P8). These findings showed that some respondents challenged the scope and coverage of information sources and did not rely on a single source.

Some participants were also marginally satisfied with the Internet, especially with social media sourcing everyday-life information, because they believed that information received from social networking sites was generally irrelevant, inaccurate and even outdated. For example, two female students were of the view that 'information received from Facebook is not authentic' (P16) and 'Facebook news is mostly fake' (P12). Two females stated that 'information on Internet confuses me e.g., Wikipedia, we cannot trust it' (P13) and that 'information on Websites was incomplete and sometimes was not updated that caused frustration' (P19). In general, the findings show that respondents were not satisfied with the authenticity of news on social media. However, none of the participants mentioned their dissatisfaction with print sources.

Problems faced by the participants in information seeking

What problems or obstacles did these respondents face while looking for everyday-life information? A majority of them mentioned that they were unsuccessful to access needed information on time and failed to get relevant information. It is obvious because they mainly depended on people/human sources for their everyday-life information seeking. The slow speed of the Internet and not knowing about where to get the advice were also important obstacles in seeking for everyday-life information. They also highlighted the lack of access to the needed information and shortage of time hindering their information seeking process.

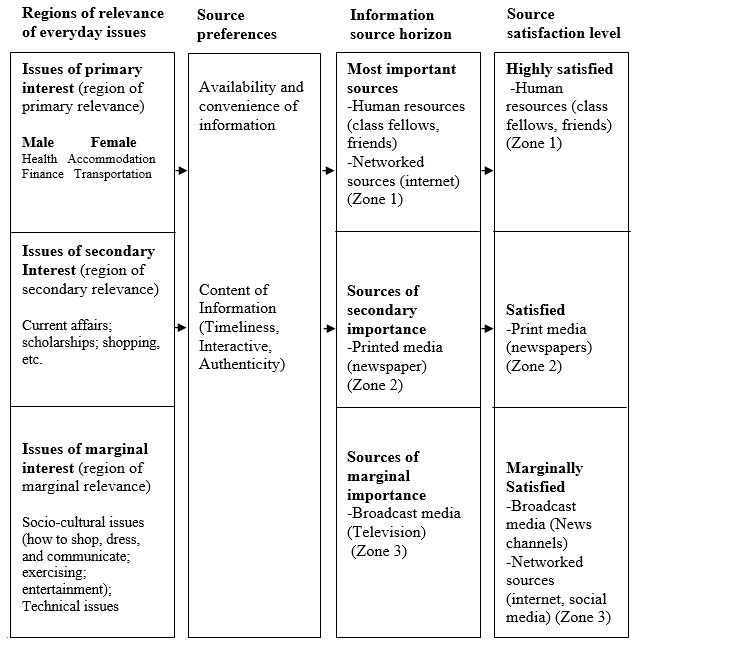

Mapping findings into Savolainen's framework

An attempt was made to map findings of the present study into the framework designed by Savolainen (2007) in order to give a more structured picture of everyday-life information seeking of resident university students with a rural background. Although this framework was developed for seeking orienting information, the mapping of our findings (Figure 3) might identify similarities and differences. However, the results also identified significant reasons for not, or reduced seeking orienting information in the local context, for example stress caused by the news media due to the current situation in the country and mistrust on social media. The present study supported and expanded the information source horizon by adding respondents' satisfaction levels (Figure 3, column 4). In order to map findings, the already utilized divisions (zone 1, 2 and 3) were selected and marked as highly satisfied (zone 1), satisfied (zone 2) and marginally satisfied (zone 3).

Our mapping, using the interview transcripts, in the zones of information horizon, satisfaction level, preference criteria and regions of relevance is based on informants' verbal responses. They were asked to rank their issues, utilised information sources and satisfaction with these sources into zones and regions of relevance (Figure 3). These participants' issues of primary interest were different for both males and females (Figure 3). The preferred primary interest issues for males were health and finance whereas the females were mainly interested in accommodation and transportation. The issues of secondary interest were socio-cultural such as shopping, what to wear, and how to dress up at different occasions. These participants were marginally interested in current affairs, career counselling, effective communication ways, exercising, and legal information.

The results show that these students placed human and networked information sources for everyday-life information seeking in Zone 1. All the participants (both male and female) placed the print media (newspapers) in Zone 2 and the broadcast media (television) in Zone 3. The criteria preferred for source selection by the participants was their availability, convenience and content of information. They selected those sources which were more interactive, authentic and up-to-date. These participants mistrusted the authenticity of print media (newspapers), broadcast media (television), and social media in providing accurate information and mentioned that they had to consult other sources for verification.

The fourth column (Figure 3) indicates respondents' satisfaction level with the utilized information sources. These results expand and complement Savolainen's (2007) framework. These students were highly satisfied with human (class and hostel fellows) information sources (Figure 3, zone 1) as they always provided them with accurate and timely information. In the category of satisfied with information sources, a majority of the participants indicated print sources (newspapers). However, a majority of these students showed their dissatisfaction while some showed their marginal satisfaction (zone 3) with broadcast (news channels) and networked sources (social media). They were of the view that these sources were not reliable and sometimes provided fake information. They had to consult other sources to check the validity of some news provided by these sources. It is interesting to note that the most important sources, networked sources (Figure 3, column 3), which were mostly used by these participants were of marginal satisfaction in terms of authenticity.

Implications for everyday-life information seeking theory and research

The population of this study consists of university resident students from rural areas of Pakistan, a developing non-western country. It extends the scope of everyday-life information seeking by adding a new dimension of rural background and provides insights into trans-national perspectives in everyday-life information seeking. There is a need to examine distinct population groups for everyday-life information seeking to further expand the existing literature, which is now more commonly focused on steps and processes.

Secondly, the study adds to the knowledge base of everyday-life information seeking by expanding the information source horizon framework developed by Savolainen (2007) by adding the aspect of information sources satisfaction level. Future researchers may use the expanded framework to get a holistic picture of different population groups. Also, there is a need to highlight reasons for information sources satisfaction level and causes of marginal satisfaction sources to get the overall view of the situation. However, future research is needed to confirm the proposed expansion of Savolainen's framework presented by the present study. It will also be desirable to replicate the study to mark social, cultural, and technological developments' influence in theory and practice.

Implications for practice

The findings have practical implications for both university administration and library staff. The administration should plan on-campus consultancy services within the present Student Affairs Office for supporting students with a rural background to overcome difficulties in light of their everyday-life information needs and adjusting to big city life. Some American universities use 'a host family' approach whereby every foreign student is attached to a local family for regular contact which makes the student's adjustment easy. Similar practices could be adopted by Pakistani universities. Library management should design services to support those provided by the university administration.

Conclusions

When young students move from rural areas to big cities for pursuing further education, they face many problems in adjusting to big city life during their studies. This is a very difficult process, especially for girls, in relatively conservative societies as they have to make socio-economic adjustments such as housing, food, health, and security, etc. (Carrillo, 2004; Hogu, 2014; McAuliffe et al., 2017; Rafiq et al., 2021). This aspect has not received due attention so far. The present study of postgraduate students who come from rural areas and reside in the university hostels face many problems for adjustment and survival. The findings highlighted their everyday-life issues (primary, secondary, and marginal) and their preferred information sources for each. These students faced different issues in their primary relevance area. Males faced health and financial issues more than females who faced accommodation and transportation issues. If these issues remained un-resolved due to lack of information and institutional support, these might affect their academic achievement and research productivity.

This study has tried to fill a gap in the existing literature by addressing the paucity of research focusing on everyday-life information seeking of resident university students with a rural background in a developing country studying in an urban university. Although these findings are context-bound, our mapping of resident students' information seeking into information source horizons and source preferences model in the context of seeking orienting information (Savolainen, 2007) and expansion is a theoretical contribution to the existing body of knowledge and will be significant for future researchers.

About the authors

Muhammad Asif Naveed is currently working at Department of Information Management, University of Sargodha, Sargodha. He completed his PhD from the Department of Information Management, University of the Punjab in 2016. He also obtained the degree of Master of Science in Public Policy from University of Management and Technology with a Gold Medal. His research interests include: information behaviour; information literacy; information anxiety;information sociology; and information policy. Corresponding email: masifnaveed@yahoo.com

Syeda Hina Batool is an Assistant Professor at Institute of Information Management, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan. She received her Ph.D. from the Information School, University of Sheffield, UK and her research interests are in information literacy specifically research conducted in school sector and information seeking. She can be contacted at hina.im@pu.edu.pk

Mumtaz Ali Anwar, is a formerly professor of several universities, namely, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Kuwait University, Kuwait, International Islamic University Malaysia, Malaysia, and King Abdul Aziz University, Jeddah. He obtained his PhD from University of Pitsbergh, USA in 1973. His research interests include: information behaviour; information anxiety; library anxiety; scientometrics, and research methodology. His contact address is anwar.mumtazali@yahoo.com

References

Note: A link from the title is to an open access document. A link from the DOI is to the publisher's page for the document.

- Agosto, D. E., & Hughes-Hassell, S. (2005). People, places, and questions: An investigation of the everyday-life information-seeking behaviors of urban young adults. Library & Information Science Research , 27(2), 141-163.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2005.01.002

- Alwis, G., Majid, S. & Chaudhry, A.S. (2006). Transformation in managers' information seeking behaviour: a review of the literature. Journal of Information Science, 32(4), 362-377. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551506065812

- Bates, J. A. (2004). Use of narrative interviewing in everyday information behavior research. Library and Information Science Research, 26(1), 15–28. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2003.11.003

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology , 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.). APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2. Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (p. 57–71). American Psychological Association.https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004.

- Bronstein, J. & Baruchson-Arbib, S. (2008). The application of cost-benefit and least effort theories in studies of information seeking behavior of humanities scholars. The case of Jewish studies scholars in Israel. Journal of Information Science, 34(2), 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551507079733

- Butterfield, L. D., Borgen, W. A., Amundson, N. E., & Maglio, A. S. T. (2005). Fifty years of the critical incident technique: 1954-2004 and beyond. Qualitative Research, 5(4), 475-497. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794105056924

- Byrne, M. (2001). Critical incident technique as a qualitative research method. AORN Journal , 74(4), 536-539. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-2092(06)61688-8

- Carey, R. F., McKechnie, L. E. F., & McKenzie, P. J. (2001). Gaining access to everyday-life information seeking. Library and Information Science Research, 23(4), 319–334. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-8188(01)00092-5

- Carrillo, B. (2004). Rural-urban migration in China: Temporary migrants in search of permanent settlement. PORTAL Journal of Multidisciplinary International Studies 1(2), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.5130/portal.v1i2.58

- Case, D. O. (2005). Principle of least effort. In: K. E. Fisher, S. Erdelez & E. F. McKechnie (Eds), Theories of information behavior: a researchers' guide (pp. 289-292). Information Today.

- Connaway, L. S., Dickey, T. J., & Radford, M. L. (2011). "If it is too inconvenient, I'm not going after it." Convenience as a critical factor in information-seeking behaviors. Library & Information Science Research, 33(3), 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2010.12.002

- Davenport, E. (2010). Confessional methods and everyday-life information seeking. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 44(1), 533–562. https://doi.org/10.1002/aris.2010.1440440119

- FitzGerald, K., Seale, N. S., Kerins, C. A., & McElvaney, R. (2008). The critical incident technique: a useful tool for conducting qualitative research. Journal of Dental Education, 72(3), 299-304. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.0022-0337.2008.72.3.tb04496.x

- Flanagan, J. C. (1954). The critical incident technique. Psychological Bulletin, 51(4), 327–358. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0061470

- Fulton, C. & Henefer. J. (2010). Information practice. In Encyclopaedia of Library and Information Sciences, 1(1), 2519-2525.

- Given, L.M. (2002). The academic and the everyday: investigating the overlap in mature undergraduates´ information-seeking behaviour. Library & Information Science Research, 24(1), 17-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-8188(01)00102-5

- Hassan, A.,& Raza, M. (2009). Migration and small towns in Pakistan. International Institute for Environment and Development. (Working paper series on Rural-Urban Interactions and Livelihood Strategies. Working paper 15). https://pubs.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/10570IIED.pdf. (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3bPvJQ5)

- Hassan, A., & Raza, M. (2013). Migration and small towns in Pakistan. Oxford University Press.

- Ikoja-Odongo, R. (2002). Insights into the information needs of women in the informal sector of Uganda. South African Journal of Libraries and Information Science, 68(1), 39-52. https://sajlis.journals.ac.za/pub/article/view/765/711. https://doi.org/10.7553/68-1-765

- Hogu, G. (2014). Urban migration trends, challenges, responses and policy in the Asia–Pacific . International Organization for Migration. https://www.iom.int/sites/default/files/WMR-2015-Background-Paper-GHugo.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3bRKKRs)

- Koo, J. H., & Gross, M. (2009). Adolescents' information behavior when isolated from peer groups: lessons from new immigrant adolescents' everyday-life information seeking. Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 46(1), 1–3. https://asistdl.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/meet.2009.1450460374. https://doi.org/10.1002/meet.2009.1450460374

- Loan, F. A. (2011). Internet use by rural and urban college students: a comparative study. Journal of Library & Information Technology, 31(6), 431–436. https://doi.org/10.14429/djlit.31.6.1317

- Loudon, K., Buchanan, S., & Ruthven, I. (2016). The everyday life information seeking behaviours of first-time mothers. Journal of Documentation, 72(1), 24-46. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-06-2014-0080

- McAuliffe, M., Kitimbo, A., Goossens, A. M., & Ullah, A.A. (2017). Understanding migration journeys from migrants' perspectives. In World Migration Report 2018. International Organization for Migration. https://publications.iom.int/fr/system/files/pdf/wmr_2018_en_chapter7.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3fi89xQ)

- McKenzie, P. J. (2003). A model of information practices in accounts of everyday-life information seeking. Journal of Documentation, 59(1), 19-40.https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410310457993

- Maguire, M., & Delahunt, B. (2017). Doing a thematic analysis: a practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. AISHE-J: The All Ireland Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education , 9(3), 3351-3364. https://ojs.aishe.org/index.php/aishe-j/article/view/335/553. (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3bPyq4c)

- Mehra, B., & Bilal, D. (2008). International students' information needs and use of technology. Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 44(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/meet.1450440373

- Meyers, E. M., Fisher, K. E., & Marcoux, E. (2007). Studying the everyday information behavior of tweens: notes from the field. Library & Information Science Research, 29(3), 310-331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2007.04.011

- Meyers, E. M., Fisher, K. E., & Marcoux, E. (2009). Making sense of an information world: the everyday-life information behavior of preteens. The Library Quarterly , 79(3), 301-341. https://doi.org/10.1086/599125

- Mooko, N. P. (2005). The information behaviors of rural women in Botswana. Library and Information Science Research, 27(1), 115-127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2004.09.012

- Nkomo, N., Ocholla, D., & Jacobs, D. (2011). Web information seeking behaviour of students and staff in rural and urban based universities in South Africa: a comparison analysis. Libri, 61(4), 281–297. https://doi.org/10.1515/libr.2011.024

- Okocha, K.F. (1995). Socio-cultural determinants of the use and transfer of scientific information by agricultural scientists in south eastern Nigeria. The International Information & Library Review, 27(4), 301-316. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1057-2317(95)80010-7

- Pettigrew, K., Fidel, R., & Bruce, H. (2001). Conceptual frameworks in information behavior. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 35, 43-78. http://faculty.washington.edu/fidelr/RayaPubs/ConceptualFrameworks.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3vm1oka)

- Rafiq, S., Iqbal, A., Rehman, S. U., Waqas, M., Naveed, M. A., & Khan, S. A. (2021). Everyday-life information seeking patterns of resident female university students in Pakistan. Sustainability, 13(7), 3884. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073884

- Savolainen, R. (1995). everyday-life information seeking: approaching information seeking in the context of 'way of life'. Library & Information Science Research, 17(3), 259-294. https://doi.org/10.1016/0740-8188(95)90048-9

- Savolainen, R. (2007). Information source horizons and source preferences of environmental activists: a social phenomenological approach. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(12), 1709–1719. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20644

- Savolainen, R. (2008). Source preferences in the context of problem-specific information. Information Processing and Management, 44(1), 274-294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2007.02.008

- Savolainen, R., & Kari, J. (2004). Conceptions of the Internet in everyday-life information seeking. Journal of Information Science, 30(3), 219-226. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551504044667

- Schutz, A., & Luckmann, T. (1973). The structures of the life-world . Northwestern University Press.

- Sin, S.-C. J. (2015). Demographic differences in international students' information source uses and everyday information seeking challenges. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41(4), 466–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.04.003

- Sin, S.-C. J., & Kim, K.-S. (2013). International students' everyday-life information seeking: The informational value of social networking sites. Library & Information Science Research, 35(2), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2012.11.006

- Sonnenwald, D. (1999). Evolving perspectives of human information behaviour: Contexts, situations, and social networks and information horizons. In T.D. Wilson & D. Allen (Eds.), Exploring the contexts of information behaviour. Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Research in Information Needs, Seeking and Use in different Contexts (pp. 176–190). Taylor Graham Publishing. http://hdl.handle.net/10150/105189

- Tury, S., Robinson, L. & Bawden, D. (2015). The information seeking behaviour of distance learners: a case study of the University of London international programmes. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41(3), 312-321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.03.008

- Williamson, K. (1998). Discovered by chance: the role of incidental information acquisition in an ecological model of information use. Library & Information Science Research, 20(1), 23-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-8188(98)90004-4

- Williamson, K., Qayyum, A., Hider, P., & Liu, Y. (2012). Young adults and everyday-life information: the role of news media. Library & Information Science Research, 34(4), 258-264. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2012.05.001

- Zaverdinos-Kockott, A. (2004). An information needs assessment in Oribi Village, Pietermaritzburg. Innovation, 29, 13-23. http://doi.org/10.4314/innovation.v29i1.26488

- Zhu, M., & Liao, XZ. (2020). Chatman’s theory of life in the round applied to the information seeking of small populations of ethnic minorities in China. Information Research, 25(3), paper 868. http://InformationR.net/ir/25-3/paper868.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3jmuAAX)

How to cite this paper

Appendix A: Interview guide

Hi, my name is _____________________. I would like to ask you some questions about you everyday information seeking practices. The purpose of this interview is to explore why and how hostel resident students with rural background look for information. This interview will last about 35-40 minutes. Your answers will be kept confidential and anonymous.

1. You may have been through a number of situations/incidents related to your everyday-life or day-to-day concerns in which you had to make a decision, find an answer to a question, solve a problem or try to understand something. Such critical incidents or situations may have been at your hostel, at university or elsewhere. Think of such critical incidents in the past two months that forced you to look for information. Please describe such important situations that come to your mind.

(Focus on the info-seeking situations and ask to follow up questions for further explanations)

- Probe: In your everyday-life, what are your most significant or information seeking situations or incidents?

- Probe: Which of these situations is marginal?

- Probe: During the past two months, what are the things that you have thought about a lot, worried about a lot, or found confusing?

2. Where did you obtain your required information?

- Probe: What has been helpful to you in trying to solve this situation or problem?

- Probe: Have you talked to anyone or done anything about this problem?

- Probe: What were your sources of information? For example: Classmates, seniors, other students, friends, teachers that you know well and feel close to...?

- Probe: Radio, television, newspapers, magazines…?

- Probe: Social networking sites, Facebook, Blog, twitter...?

- Probe: Library, Internet…? Any other…?

3. Did you ever find out your required information from a source that you had not even thought about or expecting from? If yes, was that information useful to you?

4. Overall, you have most frequently mentioned these information sources (name them) for needed information. What are your reasons for choosing these information sources?

- Probe: Ease of use, accuracy, accessibility, relevance, Interactive, user friendly, or any other

5. How satisfied were you with the information you received from information sources that you consulted (as in 5 above, it does not matter if more than one source was given).

- Satisfied. Why? _______________________________

- Dissatisfied. Why? _____________________________

6. What are the most common problems/obstacles that you encountered while seeking information you needed?

7. What is your age, gender, programme of study and home district?

8. For how many years you have been in Lahore?

Thank you for your time and interest!