The information source preferences and information monitoring behaviour of pregnant women in Pretoria, South Africa

Olubukola M. Akanbi and Ina Fourie

Introduction. Pregnant women rely on information during pregnancy for better health outcomes. This paper investigates pregnant women's interests in services that can offer health literacy and health information through appropriate sources and channels.

Method. An exploratory study was conducted in 2015 using explanatory sequential mixed methods to investigate thirty-seven women visiting two private gynaecological practices in Pretoria, South Africa. Questionnaires and an interview schedule were used for data collection.

Analysis. Descriptive statistics and thematic analysis were used for data analysis. McKenzie's two-dimensional everyday-life information practices model was slightly adapted as theoretical framework.

Results. Knowledge of pregnant women’s most preferred information sources and channels by care providers can improve maternal and infant health. Participants mostly reported some interests in information monitoring and current awareness services using mobile technologies. Pregnant women desire information monitoring on a one-off basis and/or an on-going basis.

Conclusions. Information monitoring can assist with the promotion of patient-centred information and provision of reliable and new information especially by means of freely available sources. The emphasis in more affluent communities was more on well-being than maternal and infant mortality.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper902

Introduction

Maternal and infant deaths are still a public health concern in many nations, particularly the low- and middle-income countries, such as South Africa (Moodley, et al., 2018). Globally, maternal mortality rates have reduced by 30% (from 282 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1990 to 196 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2015) (Zelop, 2018). However, developing nations still struggle with this menace, taking on 99% of the burden of maternal and infant deaths. Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest maternal deaths (Geller, et al., 2018), of which many of these deaths are preventable with adequate patient education and information (Kamali, et al., 2018; Das and Sarkar, 2014).

The provision of reliable pregnancy-related information to pregnant women is especially important if the outcomes of these pregnancies are to be healthy (Javanmardi, et al., 2018; Das and Sarkar, 2014). Information monitoring and current awareness services can assist with the promotion of patient-centred healthcare information services (Hughes and Glueckert, 2014). It can also support the provision of reliable and current information through health information technologies to pregnant women. It might improve maternal anxiety, address unmet information needs and potentially decrease maternal and infant mortality rates (Grimes, et al., 2014; Kraschnewski, et al., 2014).

Pregnancy-related information is important for women to be able to care for themselves and the unborn, especially in developing countries including South Africa (Moodley,et al., 2018). Good quality health information supports shared decision making with healthcare providers, patient education and patient empowerment to make the right decisions about their health and the baby, and to benefit from care advantages available to them (Kamali, et al., 2018; Robinson, et al., 2018). Additionally, it can inform pregnant women about obstetric danger signs that can endanger their lives and the life of the unborn (Al-Ateeq and Al-Rusaiess, 2015; Moosa and Gibbs, 2014).

Studies on pregnant women have reported some gaps in their information needs during pregnancy (Kamali, et al., 2018; Das and Sarkar, 2014). Information needs are often one-off needs suitable for a quick search for a factual piece of information e.g., medications or a retrospective search for information. Information monitoring as provided by current awareness or alerting services have been valuable in many contexts (Hughes and Glueckert, 2014; Fourie, 2006). Although the need to monitor information is not normally associated with pregnant women, it seemed as if women in progressive situations of different stages of pregnancy might have a need to monitor information on pregnancy topics.

The potential of information monitoring is noted by Dalrymple and colleagues (2013) and Lupton and Pedersen (2016). Findings from both studies revealed the benefits of text messages and mobile applications for educating pregnant women and for disseminating information on important pregnancy topics. Overall information monitoring can be an important part in the health information behaviour of pregnant women (Dalrymple, et al., 2013). Recent studies have reported the use of health information technologies by pregnant women to stay abreast of new health information (Zhu, et al., 2019; Robinson, et al., 2018) and self-monitor physiological data such as blood pressure, weight gain, physical activity, diet and foetus (Daly, et al., 2019; Lau, et al., 2018; Marko, et al., 2016). Platforms such as search engines like Google (Kraschnewski, et al., 2014), health websites (Guendelman, et al., 2017), online discussion forums (Fredriksen, et al., 2016), social networks (Harpel, 2018) and mobile applications (Lau, et al., 2018) are useful to pregnant women for monitoring health information.

Background

Millions of pregnant women around the world suffer from health problems affecting pregnancy (UNICEF, 2019). Sub-Saharan African countries have the highest rates of maternal and infant mortality globally (Geller, et al., 2018). Hence maternal healthcare is an important pointer to the reproductive healthcare quality of a nation, and it is being monitored by many international agencies (Geller, et al., 2018; McDonald, et al., 2014). Improving maternal and infant health is one of the objectives of the United Nations’ Millennium Developmental Goals, as well as the vision of the government of South Africa where this exploratory study was conducted (Lomazzi, et al., 2014).

The constant rise in infant and maternal deaths especially in developing countries raises much concern, and urgent provision of health information to pregnant women is necessary to reduce maternal and infant deaths (Mushwana, et al., 2015; Al-Ateeq and Al-Rusaiess, 2015). Most pregnant women desire health information as soon as they know about their pregnancy, because they begin to experience different bodily and immunological makeup changes (Robinson, et al., 2018; Tan and Goonawardene, 2017).

Women naturally become vulnerable and susceptible to diseases during pregnancy (Pereboom, et al., 2013). Studies have shown concern about the use of medication and vaccinations during pregnancy (Clarke, et al., 2019; Dathe and Schaefer, 2019). Various concerns about medications and vaccines can be addressed through adequate provision of health information. A study reports that pregnant women who are poor, unmarried, and uneducated suffer the most from preventable infectious diseases such as toxoplasmosis, listeriosis and cytomegalovirus (Pereboom, et al., 2013). Poor health literacy and poverty increases the risk of contracting some of these preventable diseases (Wong, et al., 2014; Song, et al., 2013). Thus, provision of healthcare information by healthcare providers and access to online sources of health information can improve maternal and infant health outcomes.

Health topics that interest pregnant women include nutrition, gestational weight gain, medication, genetic counselling, birth plans and breastfeeding (Lau, et al., 2018; Olliaro, et al., 2015). Health information monitoring, therefore, offers an affordable and convenient means of staying abreast of health information during pregnancy.

Literature Review

The literature review will cover two issues: (1) information monitoring and current awareness services; and (2) research conducted on the information needs and information seeking of pregnant women.

Information monitoring and current awareness services

Information monitoring is the dynamic process of keeping track of information on websites and webpages based on the topics of interest specified by its users (Fong, 2012; Liu, 2004). Based on this definition, information monitoring is synonymous with alerting services and has been used interchangeably in the literature with current awareness services (Fourie, 2006). Fourie (2006) notes that although the web opens new opportunities of free information monitoring, current awareness services are not limited to the Internet.

Information monitoring and current awareness services have the capacity of keeping pregnant women abreast of new pregnancy-related information (Hughes and Glueckert, 2014), and notifying them about new trends, developments, clinical findings, and useful gadgets that supports maternal health (Lau, et al., 2018; Javanmardi, et al., 2018). In addition to one-off services, they are useful for empowering women to make informed decisions with their healthcare providers, reduce maternal anxiety and increase health literacy, thereby promoting positive health outcomes (Dalton, et al., 2018; Waring, et al., 2014).

Fourie (2003) reports that current awareness services can offer aesthetic pleasure to users by creating pleasurable environments for monitoring interesting topics such as horoscopes, daily or weekly comedies, weather forecasts and travel information. Internet current awareness services offer convenient, easy and free access to information for people from all walks of life (Hughes and Glueckert, 2014; Kiscaden, 2014). Studies on current awareness services have recognised the tenacity of current awareness services to keep its users informed and updated (Mu, 2011; Mahesh and Gupta, 2008). Information monitoring services is therefore valuable to pregnant women for staying abreast of health information and tracking routine events about pregnancy.

Pregnant women have interests in various types of monitoring such as tracking of weight gain, monitoring of blood pressure and other measurable psychological and physiological biometrics for ensuring their well-being and that of the unborn (Daly, et al., 2019; Marko, et al., 2016). This paper is focused on monitoring in terms of current awareness.

Information needs and seeking of pregnant women

Pregnancy is a developmental stage in any woman’s life that requires adequate information for her to go through the stage successfully (Sharifi, et al., 2020; Kamali, et al., 2018). The maternal mortality rate is still extremely high in developing countries when compared with developed countries (Haftu, et al., 2018). Pregnant women have needs for information on a variety of health topics such as medication, gestational weight gain, nutrition, genetic counselling to mention a few (Dathe and Schaefer, 2019; Bantan and Abenhaim, 2015). It is therefore important to understand the information needs of pregnant women to provide the required health information, and preferred channels for receiving health information (Robinson, et al., 2018).

Research has shown that pregnant women in both affluent and poor socioeconomic societies need information during pregnancy (Javanmardi, et al., 2019; Coleman, et al., 2017).

The choice of channels and sources of seeking information can however be influenced by socioeconomic factors, personal experience, cultural backgrounds and level of education (Geller, et al., 2018; Das and Sarkar, 2014).

Socioeconomic factors can influence the choice of sources and channels used to search for information by pregnant women (Aborigo, et al., 2014; Das and Sarkar, 2014). Pregnant women from affluent communities very often use health information technologies such as smartphones, tablet computers, Internet, health websites, wearables, social networks, and mobile applications to stay abreast of pregnancy-related information (Zhu, et al., 2019; Javanmardi, et al., 2018). They also use these technologies for seeking advice on parenting topics and to authenticate advice received from healthcare providers (Dorst, et al., 2019).

Conversely, women who cannot afford health information technologies settle for traditional information sources, consult family members, watch television programmes on pregnancy, listen to radio programmes and use audio-visual training materials for learning about pregnancy (Asiodu, et al., 2015; Das and Sarkar, 2014). Song and colleagues (2013) confirm the dependence of poor pregnant women on family members for health advice and information. Interestingly, pregnant women from both affluent and poor socioeconomic backgrounds consult experienced women for pregnancy-related information, although, choice of information sources and channels may be different. Online discussion forums and social networks like Facebook are used by affluent women (Harpel, 2018), while face-to-face conversation is used by women who cannot afford communication technologies (Das and Sarkar, 2014). Women who can afford mobile phones sometimes utilize text messages for meeting health needs (Lau, et al., 2014; Cormick, et al., 2012).

Pregnant women use a variety of information sources and channels during pregnancy to stay abreast of health information (Grimes, et al., 2014). Recent studies are reporting the use of health information technologies for providing health information to pregnant women thereby promoting maternal health (Harpel, 2018; Kraschnewski, et al., 2014). However there is insufficient research to determine the effectiveness and efficiency of these technologies in providing adequate health information to pregnant women (Sedrati, et al., 2016; Fisher and Clayton, 2012).

A study conducted at obstetric clinics in Central Massachusetts, United States on pregnant women’s interest in healthy weight gain during pregnancy and the use of a mobile application and website shows that 86% of pregnant women are interested in receiving health information (Waring, et al., 2014). Additionally, Coleman and colleagues (2017) compared the effectiveness of mobile health intervention with improved maternal health and HIV outcomes. The study used text messages to disseminate maternal health information to women in the intervention group while those in the control group did not receive any text message intervention. The result revealed that women in the intervention group attended more antenatal visits in comparison with the control group. Birth outcomes of this intervention group also improved significantly as it increased the chances of having vaginal delivery compared with the control group.

Preferences for information sources and channels can however change over time, especially among first-time mothers (Plutzer and Keirse, 2012). Plutzer and Keirse’s (2012) cohort study found that 78% of the first-time mothers sourced information from their healthcare providers, 15.5% from parents, 21.7% from close associates and 13% from the Internet when their children started schooling.

Increased access to the Internet may change the access of information sources of poor pregnant women to smart technology (Cordoş, et al., 2017; Huberty, et al., 2013). It is noteworthy that pregnant women in affluent communities might experience many similar information needs in a less prominent manner (Laferriere and Crighton, 2017; Asiodu, et al., 2015; Pereboom, et al., 2013). The major difference between women in developing countries and poorer socio-economic groups and women in affluent communities lies in their preferences for information sources.

It is thus important for healthcare providers to discuss the most preferred information seeking methods from pregnant women to meet their information needs (Javanmardi, et al., 2019).

Theoretical framework

The use of information seeking behaviour models is particularly useful for identifying and explaining factors that affect and predict human behaviour. The development of the conceptual model is relevant in scientific investigation as it informs theory formulation, formulation of hypotheses and hypotheses testing (Järvelin and Wilson, 2003). Hence, this study adopted the McKenzie model of information practices (McKenzie, 2003). This model was developed based on the information-seeking behaviour of nineteen pregnant women based in Canada using a constructionist discourse analysis approach.

McKenzie (2003) proposed the model of information seeking in everyday life. This model suggests a need for more attention on the less active and social components of information seeking behaviour. Savolainen (1995) explores the relevance of less active information seeking behaviour to determine the information activities in everyday life context. The model also stresses the inadequacy of many information seeking behaviour models to capture the less active information seeking of individuals in social settings.

McKenzie’s model of information practices in everyday life encompasses four modes of information seeking, and it includes active seeking, active scanning, non-directed monitoring and information seeking by proxy (Yeoman, 2010). This model assumes that pregnant women are involved in information practices beyond active information seeking and get involved in other information seeking activities. Findings from her research revealed that her research participants (pregnant women carrying twins) were engaged in active seeking (purposely looking for information in an already known information space), active scanning (browsing or scanning a likely information space or location with the assurance of getting the needed information), non-directed monitoring (incidental encountering of information in an unlikely location) and by proxy (interaction with useful information through an intermediary or referral).

Additionally, Wilson (1977) asserts that information is often uncovered in everyday life through less-directed information seeking, like monitoring or scanning the physical environment. Ellis and Haugan (1997) also identified monitoring as one of the information seeking pattern seen among researchers in their study. Hence, directed monitoring was added to McKenzie’s modes of information seeking. Directed monitoring is defined as tracking specific information on a given topic on an on-going basis for a specific purpose (Akanbi, 2016).

Advancement in health information technologies has advanced the concept of monitoring information (Lau, et al., 2018; Daly, et al., 2017), especially in the digital context where users use notifications and alerts to subscribe to webpages to be routinely notified with new information on specified topics of interest over a specified period of time. Research on pregnant women have shown that they wish to monitor information using mobile devices, applications, and Internet-sourced platforms (Lau, et al., 2018; Harpel, 2018; Daly, et al., 2017).

This study therefore slightly adapted the four modes of information seeking from McKenzie’s model and added two modes to investigate the usefulness of health information monitoring and current awareness services during pregnancy. Directed monitoring and passive seeking and accidental encountering were included as the two other modes of information seeking.

The table below summarises the incorporation of the six modes of information seeking to understand the information behaviour of pregnant women based on findings from the participants.

Contextualizing the McKenzie model

Individual-in-context (recognition of information needs)

| Modes (activities undertaken when searching for information) | Description of modes | Examples from the study findings |

|---|---|---|

| Active seeking | Actively seeking information, advice, support from healthcare providers during prenatal visits to gynaecologists; searching for health topics from books and magazines such as Your Pregnancy; searching for health information on the Internet. | Consciously making a list of questions to ask healthcare providers Active involvement with pregnancy-related online discussion groups, e.g., consciously reading other pregnant women’s comments and experiences on blogs, online discussion groups. |

| Active scanning | Browsing through health magazines or pamphlets in the healthcare providers’ consulting rooms; browsing pregnancy-related websites; browsing in a bookstore for health-related materials. | Being attentive to other pregnant women’s discussions at the healthcare provider’s consulting rooms. Being attentive to family members with experience of pregnancy for second opinion on pregnancy issues. |

| Non-directed monitoring | Finding pregnancy-related information while scanning magazines or newspapers for other purposes, for other reasons. Finding pregnancy-related information in unlikely places and circumstances, e.g., when sitting in traffic. |

Finding information through seeing a diseased child (disease that could have been prevented with right medication, such as iron supplements). Finding pregnancy-related information by overhearing other people’s conversation in an unfamiliar place, e.g., at an informal gathering. |

| Directed monitoring | Subscribing to magazines or relevant publications on pregnancy. Receiving pregnancy-related information by monitoring Internet websites, e.g., Baby Centre. |

Creating alerts on health topics on websites, e.g., alerts on Down syndrome. Watching online information sources such as YouTube videos. Using mobile app such as Bounty for staying abreast with weekly foetal development. |

| By proxy | Asking other people to search for information. Relying on other people for information referral. |

Depending on others to be updated with information either through speaking in person or sending information electronically |

| Passive seeking and accidental encountering | Getting information or advice without making any effort or asking. | Getting information when a protruded stomach is seen. Picking up information from other people’s discussions. |

| Note: What McKenzie referred to as information practices are similar to the activities reported by researchers who use information behaviour as the collective term. Information behaviour will replace information practice in this study. | ||

Participants experienced information needs and sought for information at various intervals of their pregnancy. Women who had already given birth after earlier pregnancies also noted that they sought information in the period immediately after giving birth. Information seeking was not a one-off event; it was repeated. Sometimes there was a need for ongoing monitoring of information and especially new reports on experiences by other women. The needs for information monitoring applied to the period of pregnancy as well as the period immediately after birth were closely related to the progressive nature of pregnancy. The progressive nature of pregnancy is another focus of McKenzie’s research (2003, 2004).

Methods

Population and sample

The data used for this study were collected between August and October 2015 at two more affluent practices of gynaecologists in Pretoria (South Africa). Both gynaecologists gave permission for data collection. The research participants were pregnant women visiting the two practices for routine check-ups (also known as prenatal care). Before recruitment, the researcher presented invitation flyers to the receptionists of both practices to solicit for participation from interested and willing pregnant women. A total of forty women showed interests in participating, however some of them often did not have enough time between the arrival and consultation time. Hence, a few dropped-out of the study. In all, thirty-seven pregnant women participated.

Purposive and convenience sampling techniques were used because of the availability and accessibility of the participants (Pickard, 2013)

Research design

The objectives of this exploratory study were to investigate the need for information monitoring and current awareness by pregnant women and to identify the most appropriate information sources and channels for providing health information for them especially regarding current awareness services. The primary aim was to use the findings to contribute to efforts to promote health literacy and provision of relevant health information for pregnant women. The study was guided by the following research question: What are the information needs and information behaviour of pregnant women, with specific reference to needs to monitor new information and the use of current awareness services?

Mixed methods design, and specifically, explanatory sequential mixed methods, were used for this study. Mixed methods involve the combination of both qualitative and quantitative research and data to understand a research problem (Creswell and Creswell, 2018). Explanatory sequential mixed methods involve the collection of quantitative data first, followed by qualitative data for research purpose. The quantitative data are better understood with findings from the qualitative data as it gives further explanations on the research problem (Creswell and Creswell, 2018; Creswell and Tashakkori, 2007). Explanatory sequential mixed methods seem plausible for this study because it permits understanding the participants using both quantitative and qualitative data, which ultimately gives a more robust picture of the phenomena being studied. A total of thirty-seven women completed copies of the questionnaires and eleven out of them participated in the interviewing sessions. Copies of questionnaires were used to gather the quantitative data while semi-structured interviews were used to gather the qualitative data from the participants.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyse the quantitative data and thematic analysis was used to analyse the qualitative data collected from the participants. Pseudonyms were used to ensure anonymity of each participant.

The researcher ensured ethical clearance from the research ethics and integrity committees of the Faculty of Engineering, Built Environment and Information Technology and the Faculty of Health Sciences of the University of Pretoria before data collection. All participants signed copies of the informed consent forms before participating in the study.

Results: quantitative findings from the questionnaire

This section reports on the descriptive statistics for the demographic data of the participants and discusses the analysis of responses to the questionnaire. Although thirty-seven women (N=37) completed the questionnaire, they did not always answer all questions. When reporting on findings on the different issues, N is sometimes shown as less than thirty-seven.

Although Akanbi (2016) focused on a wider spectrum of issues, this paper reports only on the needs for health information monitoring and current awareness services.

| Variables | Responses | % |

|---|---|---|

| Stage of pregnancy (n=40) | ||

| 1-10 weeks | 2 | 5.0% |

| 11-20 weeks | 8 | 20.0% |

| 21-30 weeks | 11 | 27.5% |

| 31-40 weeks | 17 | 42.5% |

| More than 40 | 2 | 5.0% |

| Number of pregnancies (n=39) | ||

| First time | 12 | 30.8% |

| One full term | 9 | 23.1% |

| Two full terms | 8 | 20.5% |

| Three full terms | 10 | 25.6% |

| Marital status (n=40) | ||

| Married | 29 | 72.5% |

| Single | 9 | 22.5% |

| Divorced | 1 | 2.5% |

| Other (boyfriend) | 1 | 2.5% |

| Level of education (n=40) | ||

| High school, but grade12 not completed | 1 | 2.5% |

| Grade 12 | 14 | 35.0% |

| Diploma | 9 | 22.5% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 7 | 17.5% |

| Honours degree | 5 | 12.5% |

| Master’s degree | 3 | 7.5% |

| Other post-high school qualification | 1 | 2.5% |

| Approximate number of prenatal visits (n=38) | ||

| One time | 2 | 5.3% |

| Two times | 1 | 2.6% |

| Three times | 5 | 13.2% |

| Four times | 7 | 18.4% |

| Five times | 3 | 7.9% |

| Six times | 4 | 10.5% |

| More than 6 times | 16 | 42.1% |

| Reasons for prenatal visits (n=40) | ||

| Routine check-up | 40 | 100% |

| Obstetrics danger signs | 1 | 2.5% |

Table 2 summarises the descriptive statistics of the participants. It includes the stage of pregnancy, number of pregnancies, marital status, highest level of education and number of prenatal visits. These factors were added, based on the literature review (e.g., Lindgren, et al., 2017). Most of the participants were 31-40 weeks into their pregnancy (17/40, 42.5%), while a small number were more than 40 weeks pregnant (2/40, 5.0%). A high number of the women were first-time pregnant women (12/39, 30.8%), and most of the participants were married (29/40, 72.5%). All the participants had some level of secondary or tertiary education. Most participants indicated grade 12 (14/40, 35.0%) as their highest qualification, followed by diplomas (9/40, 22.5%). (Grade 12 is the final school year in South Africa.) All the participants had prenatal visits to their gynaecologists, except for one who learned that she was pregnant on the day of the interview. Most women had more than six prenatal visits (16/38, 42.1%) with the gynaecologists. The reason for prenatal visit most frequently mentioned was for routine check-ups (40/40, 100%). Besides routine check-ups, confirmation of pregnancy was another reason mentioned for prenatal visits.

| Preference for information sources (N=36) | Not important | Slightly important | Important | Very important | Weighted score | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | No. | No. | No. | |||

| Family members | 3 | 2 | 14 | 20 | 90 | =1 |

| Healthcare providers | 2 | 1 | 10 | 23 | 90 | =1 |

| Internet | 2 | 5 | 16 | 15 | 82 | 3 |

| Search engines | 4 | 7 | 15 | 12 | 73 | 4 |

| Books | 2 | 6 | 15 | 12 | 72 | 5 |

| Television programmes | 5 | 7 | 16 | 10 | 69 | 6 |

| Brochures | 5 | 7 | 19 | 5 | 60 | 7 |

| Magazines | 4 | 13 | 12 | 7 | 58 | 8 |

| Pamphlets | 5 | 10 | 17 | 4 | 56 | 9 |

| E-mails | 6 | 11 | 11 | 7 | 54 | 10 |

| Bulletins | 6 | 11 | 13 | 5 | 52 | 11 |

| Radio programmes | 8 | 9 | 12 | 6 | 51 | 12 |

| Electronic newsletters | 7 | 10 | 14 | 4 | 50 | 13 |

| Friends | 8 | 10 | 12 | 5 | 49 | =14 |

| Blogs | 5 | 17 | 10 | 4 | 49 | =14 |

| Social networks | 9 | 9 | 11 | 6 | 49 | =14 |

| Audio-visual materials | 9 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 48 | 17 |

| Discussion groups (online forum) | 10 | 9 | 12 | 4 | 45 | 18 |

| Text messages (SMS) | 9 | 15 | 9 | 2 | 39 | 19 |

Participants’ preferences for information sources during their current pregnancy were determined. The 'Weighted score' was determined by assigning the values of 0, 1, 2, and 3 to the levels of importance (i.e., No importance = 0), and the sources were ranked on this basis. Based on data on Table 3, ‘very important’ information sources included healthcare providers (23/36, 63.9%), family members (20/36, 55.6%) and the Internet (15/36, 41.7%). Information sources marked as ‘important’ included brochures (19/36, 52.8%), pamphlets (17/36, 47.2%), the Internet and television programmes (16/36, 44.4%). ‘Slightly important’ information sources were blogs (17/36, 47.2%) and text messages (SMS) (15/36, 41.7%), while information sources marked as ‘not important’ included discussion groups (10/36, 27.8%), text messages, audio-visual materials and social networks (each with 9/36, 25%).

| Active seeking (turning to sources for a specific purpose) (N=37). | Already happened | Highly likely | Likely | Unlikely | Highly unlikely | Weighted index | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I will ask my healthcare providers(s) for pregnancy-related information. | 28 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4.54 | 1 |

| I will make a list of questions prior to my appointment with my healthcare provider(s). | 8 | 12 | 12 | 5 | - | 3.62 | 8 |

| I will search for information by buying pregnancy-related information materials or publications. | 15 | 8 | 12 | 2 | - | 3.97 | 3 |

| I will ask friends and family members for pregnancy-related information. | 13 | 9 | 12 | 3 | - | 3.86 | 5 |

| Active scanning and browsing (turning to sources in the hope that you might find something of interest). | |||||||

| I will browse through bookshelves in bookshops for pregnancy-related information. | 6 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 1 | 3.24 | 13 |

| I will browse through bookshelves in libraries for pregnancy-related information. | 1 | 7 | 8 | 17 | 4 | 2.57 | 18 |

| I will look around in the healthcare provider’s consulting rooms for pregnancy-related information. | 10 | 10 | 15 | 1 | 1 | 3.73 | 6 |

| I will check in maternity centres for pregnancy-related information. | 7 | 5 | 16 | 8 | 2 | 3.27 | 11 |

| I will look for information on pregnancy by flipping through information materials on pregnancy and related issues. | 8 | 9 | 15 | 5 | - | 3.54 | 10 |

| I will browse the Internet for information on pregnancy and related issues. | 22 | 6 | 8 | - | 1 | 4.30 | 2 |

| Non-directed monitoring of information (pursuing no specific goal). | |||||||

| I might glance through magazines or newspaper for other purposes and then find pregnancy-related information. | 9 | 12 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 3.62 | 8 |

| I could watch TV or listen to a radio programmes, and then come across useful information on pregnancy. | 9 | 13 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 3.65 | 7 |

| I might find pregnancy-related information in unfamiliar places and circumstances, e.g., seeing a mother pushing a double baby stroller. | 6 | 5 | 17 | 8 | - | 3.16 | 15 |

| Directed monitoring (monitoring sources on an on-going bases for a specific purpose). | |||||||

| I might subscribe to magazines or relevant publications on pregnancy. | 4 | 7 | 15 | 7 | 3 | 2.97 | 16 |

| I might find pregnancy-related information through e-mail alerts. | 5 | 10 | 13 | 5 | 2 | 3.14 | 17 |

| I could receive pregnancy-related information by monitoring the Internet websites. | 14 | 12 | 8 | 2 | - | 3.95 | 4 |

| By proxy (getting information through the help of somebody else searching on your behalf). | |||||||

| I will ask other people to search on my behalf for pregnancy-related information. | 3 | 7 | 4 | 14 | 8 | 2.46 | 19 |

| I will rely on other people to refer me to information or people with information. | 2 | 3 | 9 | 9 | 13 | 2.16 | 21 |

| Family members, friends, colleagues and associates scan various pregnancy-related information sources on my behalf and bring information to my attention. | 3 | 5 | 10 | 6 | 12 | 2.41 | 20 |

| Passive seeking and accidental encountering (getting information without asking). | |||||||

| I will get information and advice when people see my protruded stomach. | 8 | 3 | 11 | 9 | 5 | 2.92 | 17 |

| I will pick up pregnancy-related information from other people’s discussions, e.g., in healthcare provider’s consulting room, at the hairdresser. | 7 | 8 | 11 | 6 | 6 | 3.19 | 14 |

| I will pick up pregnancy-related information when friends and family bring pregnancy issues to my attention. | 6 | 9 | 11 | 6 | 4 | 3.11 | 12 |

Table 4 is derived from section 8 of Appendix A, which explored the participants' ways of information seeking and factors affecting information seeking. The question was divided into six modes of information seeking: active seeking, active scanning, non-directed monitoring, by proxy, directed monitoring, and passive seeking and accidental encountering. All participants could select from a five-point Likert scale options being, already happened, highly likely, likely, unlikely, and highly unlikely. The higher weighting being already happened and highly likely. the Weighted score was derived according to the formula (Number of votes x Weighting for column 1 (i.e., 5)) + (Number of votes * Weighting for column 2 (i.e., 4)) + Number of votes x Weighting for Column 3 (i.e., 3)) + (Number of votes x Weighting for column 4 (i.e., 2)) + (Number of votes x Weighting for column 5 (i.e., 1))/ Total number of votes.'

Analysis reveals that ‘I will ask my healthcare provider(s) for pregnancy-related information' ranked first place. Active scanning and browsing, ‘I will browse the Internet for information on pregnancy and related issues’ ranked second place. Active seeking, ‘I will search for information by buying pregnancy-related information materials or publications' ranked third place and direct monitoring ‘I could receive pregnancy-related information by monitoring the Internet websites' was in fourth place.

The information seeking mode with the lowest ranking was information seeking by proxy, ‘I will rely on other people to refer me to information or people with information'.

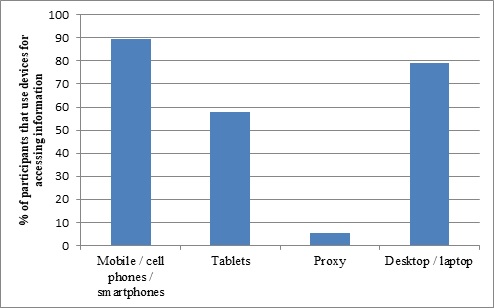

Figure 1 shows the means used by the participants during the current pregnancy.

Most of the participants owned mobile or cell phones or smartphones and used these devices for accessing information (34/38, 89.5%). A smaller number reported that they used desktops or laptops (30/38, 78.9%), followed by tablet computers (22/38, 57.9%). Only two participants reported that they had used proxy information seeking (2/38, 5.3%).

Qualitative findings from the interviews

The researcher conducted interviews with eleven pregnant women, seven from site A and four from site B. Women at site A were more inclined to participate in interviews, while at site B they were often in a hurry to leave after their consultation with the gynaecologist. There was seldom enough time between their arrival at the medical practices and their consultation session.

Thematic analysis was used to identify and categorise themes from data collected from participants (Fenwick, et al., 2015; Saldaña, 2013). From the discussions, we noted the following themes, which are in line with the questions asked.

Ways of staying abreast of pregnancy-related information

Even though women responded on means of information monitoring, answers often showed that it was more a case of repeating a one-off need for re-assurance, advice and comfort. The participants all had unique ways and preferences for staying abreast with pregnancy-related information. These included the following:

a) Blogs: Five out of ten participants showed interest in blogs. Some participants explained that blogs provided them with a sense of comfort when they read about how others dealt and coped with similar health conditions and similar situations.

Mary: ‘I use blogs because of gaining actual experiences from other people.’

Ruby: ‘I read experiences shared on blogs during difficult time.’

b) Online information (Internet): Ten out of the eleven participants used the internet for staying abreast with pregnancy-related information. They did not at this stage elaborate on their information needs.

Mary: ‘I read online information by browsing the Internet.’

Margaret: ‘I search the Internet for useful information.’

Candice: ‘I used Internet but consult doctor, family members to confirm the needed information.’

c) Websites: The most cited website was Babycenter. Others also mentioned You, baby and I

d) YouTube videos: Only one participant mentioned the use of YouTube videos for staying abreast with pregnancy-related information. Mary explained that she watched YouTube videos to learn about breastfeeding.

Mary: ‘I gain actual experiences from watching other people through YouTube videos.’

e) Magazines: Seven of the eleven participants mentioned that they had read magazines for staying abreast with pregnancy-related information. The magazines cited most often were Baba & Kleuter (Afrikaans magazine – translation: Baby & Toddler) and Your Pregnancy.

Joan: ‘I usually read Baba & Kleuter.’ Margaret: ‘I use Your Pregnancy.’

f) Family members: Five of the eleven participants used family members for staying abreast with pregnancy-related information. Family members cited most often included the mother (noted by two participants), spouses (noted by two participants) and siblings in the medical profession (noted by one participant).

Linda: ‘I have asked my mum and sisters but they suggest the traditional way of delivery.’

In such cases, it was more a case of participants repeatedly turning to family members as an information source on an ongoing basis than information monitoring as traditionally interpreted.

g) Pamphlets: Two of the eleven participants used pregnancy-related pamphlets for staying abreast with information.

Isabella: ‘I read pamphlets displayed at doctor’s office.’

Isabella: searched for information on special fitness classes e.g., yoga classes for women who had undergone a caesarean session. It seemed like she did this on an ongoing basis. In such cases, they constantly looked out for new pamphlets that might become available.

h) Friends: Some participants explained that they spoke with their friends, especially ones with babies or past experiences. Six of the eleven participants consulted friends for staying abreast with pregnancy-related information.

Dolly: ‘I speak with friends with toddlers.’

Information on nutrition, weight loss after pregnancy, nipple cream, milestone of a baby, breastfeeding pillows and humidifiers were solicited from friends. Turning to family members and constant turning to humans rather than traditional information monitoring stood out.

i) Television programmes: Only one of the participants noted that she watched pregnancy and parenting programmes on television, but none of them stated the title of any of the programmes. (This participant was the youngest of them all, a high-school girl.)

She mentioned that she needs information on methods of delivery, skin care, nutrition, healthcare facilities in the area, and that she monitors this on an ongoing basis.

j) Spouses: Only two participants indicated that they consulted their spouses to stay abreast with pregnancy-related information. A woman noted that she browsed the Internet regularly but confirmed the reliability of the online information with her spouse (a medical doctor).

Mary: ‘So I rely on the Internet for information on safety of the baby because I am in my forties and regularly ask my husband on information in this regard.’

k) App on the phone (Bounty App): One of the eleven participants used a mobile app, namely Bounty App, for staying abreast with pregnancy-related information.

Joan: ‘It provides information about the baby on a weekly basis.’

l) Personal healthcare provider (gynaecologist and midwives): All the participants mentioned consulting their healthcare providers. They all considered them as the most sought for staying abreast of pregnancy-related information. But they were said to lack the emotional intelligence to meet emotional needs hence they turned to blogs for receiving reassurance and comfort.

Joy: ‘Whatever I read on the Internet I still have to confirm with my doctor.’ Joan: ‘I don’t go on Google; I rather call my doctor.’

Some of the topics sought about for ongoing monitoring were vaccinations, progression of pregnancy, monitoring blood pressure, nutrition, supplements (whether to take Panadol or not), abnormalities associated with high risk pregnancy, necessary blood tests.

m) Newsletters: One of the eleven participants used newsletters for staying abreast with pregnancy-related information.

Candice: ‘I read newsletters from credible sites’.

She read on topics on getting a routine/sleeping pattern for the baby, right portion of feeding for mother and baby, family planning etc. For her this was an ongoing need to find new information. Candice did not mention the specific newsletter.

n) E-mails: Only one participant (Candice) mentioned the use of e-mail for staying abreast with pregnancy-related information. She receives e-mail alerts from pregnancy forums and platforms she subscribed to e.g., babycenter.com.

o) Books: Two of the eleven participants used books for staying abreast with pregnancy-related information. Judith and Margaret explained that they read pregnancy-related books for staying abreast with pregnancy-related information, but they could not remember the names of the authors or titles of the books they had read. Again, it seemed as if their needs relate to the progressive situation of pregnancy and the ongoing changes in their bodies.

Discussion

Maternal and infant mortality rates for developing countries are alarming. Adequate health information is one of the fundamental needs of a woman to go through pregnancy successfully. Therefore, understanding the most preferred methods of receiving health information is important to reduce deaths and morbidity associated with pregnancy in any context.

The results of this study revealed that pregnant women engaged in one-off active information seeking, ongoing repeat of questions, and searching of information on issues of concern. For some of the women, pregnancy induced the desire to stay abreast of pregnancy information from a variety of available sources. They desire to stay abreast with new information, as well as new postings by other women on their views and experiences of pregnancy.

Findings from this study revealed that women were not only involved in active seeking (purposely looking for information in a known source), active scanning (looking for information in a likely source with the hope of finding useful information), non-directed monitoring (incidental encountering of information but without a specific goal) and by proxy (interacting with useful information through a referral) information seeking, they were also involved in directed monitoring (monitoring information sources on an ongoing basis for a specific purpose) and passive and accidental encountering. It also shows that information seeking was not a one-off event but repeated until the information need is met. Additionally, due to the progressive nature of pregnancy, pregnant women desire information all through pregnancy and afterwards. Thus, all the six modes of information seeking are relevant for capturing the richness of pregnant women’s information seeking behaviour.

The experience of pregnancy is similar for both women living in developed and developing nations from a biological point of view, however improved healthcare is more noticeable in developed nations than developing nations. Models based on data from pregnant women in affluent communities tends to be applicable to women in less affluent communities because pregnancy is a unique condition that demands adequate healthcare and information for healthy outcomes. Every mother, irrespective of geographic location, naturally seeks for information resources in order to have healthy outcomes. Also, ways of seeking information are similar for both women living in developed and developing nations but there might be difference in the information sources consulted. Affluent women rely and use health technologies and healthcare whereas less affluent women rely on traditional information sources and available care they can access.

Furthermore, resear has shown that pregnant women, irrespective of socio-economic background, access variety of information channels and sources to reduce uncertainty associated with pregancy. They use varying information sources for participating in shared decisions making with healthcare providers, staying abreast of relevant information, self-managed their health and that of the newborn. Pregnant women in affluent communities seem to prefer using Internet and mobile technologies for staying abreast of health information.

The relevance of the four modes of information practices by McKenzie (2003) seems plausible to create the right channels and sources useful to pregnant women. It also supports the concept of directed monitoring for receiving relevant information on an ongoing basis and could facilitate good communication between healthcare providers and patients through Internet and mobile technologies during pregnancy. It also suggests the practicality of libraries and information centres offering current awareness services to women to reduce the anxiety associated with pregnancy.

Limitation of the study

The study used only participants visiting two more affluent medical practices of gynaecologists in one city specifically Pretoria (South Africa). The empirical findings in terms of the preferences for information sources and channels by pregnant women might be somewhat different from women residing in townships and rural settlements, and in other countries, but there might also be overlaps as we showed in the literature review. There might also be some differences regarding needs for information monitoring and current awareness services and the channels preferred for these. Despite limitations, the study and findings can shed the way for further data collection amongst other groups and in other contexts.

Conclusion

Health information monitoring and current awareness services are important for meeting the information needs of pregnant women. Pregnant women are often actively involved with information through various stages of their pregnancy and immediately after birth. Hence, these services are advantageous to update women on an ongoing basis with new information and the experiences and views of others can be useful.

Mobile technology and devices are convenient channels for keeping pregnant women abreast of health information during pregnancy as well as in the period immediately after birth. Some of the other information sources and channels noted in this study can also support the purpose of information monitoring.

About the authors

Olubukola M. Akanbi is a Masters student, Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria, South Africa. She can be contacted at olubukola_ogundele@yahoo.com

Ina Fourie is Professor and Head of the Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria. She can be contacted at ina.fourie@up.ac.za

References

- Aborigo, R. A., Moyer, C. A., Gupta, M., Adongo, P. B., Williams, J., Hodgson, A., Allote, P., & Engmann, C. M. (2014). Obstetric danger signs and factors affecting health seeking behaviour among the Kassena-Nankani of Northern Ghana: a qualitative study. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 18(3), 78-86.

- Akanbi, O. M. (2016). Information monitoring and current awareness services supporting the information behaviour of pregnant women. [Unpublished Master's dissertation]. University of Pretoria. https://repository.up.ac.za/handle/2263/61316 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2Sm8wie)

- Al-Ateeq, M. A., & Al-Rusaiess, A. A. (2015). Health education during antenatal care: the need for more. International Journal of Women’s Health, 7, 239-242. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S75164

- Asiodu, I. V., Waters, C. M., Dailey, D. E., Lee, K. A., & Lyndon, A. (2015). Breastfeeding and social media among first-time African American mothers. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing: JOGNN / NAACOG, 44(2), 268-278. https://doi.org/10.1111/1552-6909.12552

- Bantan, N., & Abenhaim, H. A. (2015). Vaginal births after caesarean: what does Google think about it? Women and Birth, 28(1), 21-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2014.10.004

- Clarke, R. M., Sirota, M., & Paterson, P. (2019). Do previously held vaccine attitudes dictate the extent and influence of vaccine information-seeking behavior during pregnancy? Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 15(9), 2081-2089. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2019.1638203

- Coleman, J., Bohlin, K. C., Thorson, A., Black, V., Mechael, P., Mangxaba, J., & Eriksen, J. (2017). Effectiveness of an SMS-based maternal mHealth intervention to improve clinical outcomes of HIV-positive pregnant women. AIDS Care, 29(7), 890-897. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2017.1280126

- Cordoş, A.-A., Bolboacă, S. D., & Drugan, C. (2017). Social media usage for patients and healthcare consumers: a literature review. Publications, 5(2), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications5020009

- Cormick, G., Kim, N. A., Rodgers, A., Gibbons, L., Buekens, P. M., Belizán, J. M., & Althabe, F. (2012). Interest of pregnant women in the use of SMS (short message service) text messages for the improvement of perinatal and postnatal care. Reproductive Health, 9, article 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-9-9

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed method approaches (5th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Creswell, J. W., & Tashakkori, A. (2007). Editorial: developing publishable mixed methods manuscripts. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(2), 107-111. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689806298644

- Dalrymple, P. W., Rogers, M., Zach, L., Turner, K., & Green, M. (2013). Collaborating to develop and test an enhanced text messaging system to encourage health information seeking. Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA, 101(3), 224-227. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.101.3.014

- Dalton, J. A., Rodger, D., Wilmore, M., Humphreys, S., Skuse, A., Roberts, C. T., & Clifton, V. L. (2018). The Health-e babies app for antenatal education: feasibility for socially disadvantaged women. PLoS ONE, 13(5), e0194337. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194337

- Daly, L. M., Boyle, F. M., Gibbons, K., Le, H., Roberts, J., & Flenady, V. (2019). Mobile applications providing guidance about decreased fetal movement: review and content analysis. Women and Birth: Journal of the Australian College of Midwives, 32(3), e289-e296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2018.07.020

- Daly, L. M., Horey, D., Middleton, P. F., Boyle, F. M., & Flenady, V. (2017). The effect of mobile application interventions on influencing healthy maternal behaviour and improving perinatal health outcomes: a systematic review protocol. Systematic Reviews, 6, article 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0424-8

- Das, A., & Sarkar, M. (2014). Pregnancy-related health information-seeking behaviors among rural pregnant women in India: validating the Wilson model in the Indian context. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 87(3), 251-262.

- Dathe, K., & Schaefer, C. (2019). The use of medication in pregnancy. Deutsches Arzteblatt International, 116(46), 783-790. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2019.0783

- Dorst, M. T., Anders, S. H., Chennupati, S., Chen, Q., & Purcell Jackson, G. (2019). Health information technologies in the support systems of pregnant women and their caregivers: mixed-methods study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(5), e10865. https://doi.org/10.2196/10865

- Ellis, D., & Haugan, M. (1997). Modelling the information seeking patterns of engineers and research scientists in an industrial environment. Journal of Documentation, 53(4), 384-403. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000007204

- Fenwick, J., Toohill, J., Creedy, D. K., Smith, J., & Gamble, J. (2015). Sources, responses and moderators of childbirth fear in Australian women: a qualitative investigation. Midwifery, 31(1), 239-246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2014.09.003

- Fisher, J., & Clayton, M. (2012). Who gives a tweet: assessing patients’ interest in the use of social media for health care. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 9(2), 100-108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6787.2012.00243.x

- Fong, S. (2012). Framework of competitor analysis by monitoring information on the web. Journal of Emerging Technologies in Web Intelligence, 4(1), 77-83. https://doi.org/10.4304/jetwi.4.1.77-83

- Fourie, I. (2006). How LIS professionals can use alerting services. Chandos. http://dx.doi.org/10.1533/9781780630960

- Fourie, I. (2003). How can current awareness services (CAS) be used in the world of library acquisitions? Online Information Review, 27(3), 183-195. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/14684520310481409

- Fredriksen, E. H., Harris, J., & Moland, K. M. (2016). Web-based discussion forums on pregnancy complaints and maternal health literacy in Norway: a qualitative study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(5), e113. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5270

- Geller, S. E., Koch, A. R., Garland, C. E., MacDonald, E. J., Storey, F., & Lawton, B. (2018). A global view of severe maternal morbidity: moving beyond maternal mortality. Reproductive Health, 15(1), article 98. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0527-2

- Grimes, H. A., Forster, D. A., & Newton, M. S. (2014). Sources of information used by women during pregnancy to meet their information needs. Midwifery, 30(1), e26-e33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2013.10.007

- Guendelman, S., Broderick, A., Mlo, H., Gemmill, A., & Lindeman, D. (2017). Listening to communities: mixed-method study of the engagement of disadvantaged mothers and pregnant women with digital health technologies. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(7), e240. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7736

- Haftu, A., Hagos, H., Mehari, M.-A., & G/Her, B. (2018). Pregnant women adherence level to antenatal care visit and its effect on perinatal outcome among mothers in Tigray public health institutions, 2017: Cohort study. BMC Research Notes, 11(1), article 872. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-018-3987-0

- Harpel, T. (2018). Pregnant women sharing pregnancy-related information on Facebook: web-based survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(3), e115. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7753

- Huberty, J., Dinkel, D., Beets, M. W., & Coleman, J. (2013). Describing the use of the internet for health, physical activity, and nutrition information in pregnant women. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 17(8), 1363-1372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-012-1160-2

- Hughes, A. M., & Glueckert, J. P. (2014). Providing dental current awareness to faculty and residents. Medical Reference Services Quarterly, 33(1), 29-38. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2014.866480

- Järvelin, K., & Wilson, T. D. (2003). On conceptual models for information seeking and retrieval research. Information Research, 9(1), paper 163. http://informationr.net/ir/9-1/paper163.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20210413010132/http://informationr.net/ir/9-1/paper163.html)

- Javanmardi, M., Noroozi, M., Mostafavi, F., & Ashrafi-rizi, H. (2019). Challenges to access health information during pregnancy in Iran: a qualitative study from the perspective of pregnant women, midwives and obstetricians. Reproductive Health, 16(1), article 128. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0789-3

- Javanmardi, M., Noroozi, M., Mostafavi, F., & Ashrafi-rizi, H. (2018). Internet usage among pregnant women for seeking health information: a review article. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research, 23(2), 79-86. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijnmr.IJNMR_82_17

- Kamali, S., Ahmadian, L., Khajouei, R., & Bahaadinbeigy, K. (2018). Health information needs of pregnant women: information sources, motives and barriers. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 35(1), 24-37. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12200

- Kiscaden, E. (2014). Creating a current awareness service using Yahoo! Pipes and libGuides. Information Technology and Libraries, 33(4), 51-56. https://doi.org/10.6017/ital.v33i4.5273

- Kraschnewski, J. L., Chuang, C. H., Poole, E. S., Peyton, T., Blubaugh, I., Pauli, J., Feher, A., & Reddy, M. (2014). Paging “Dr. Google”: does technology fill the gap created by the prenatal care visit structure? Qualitative focus group study with pregnant women. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(6), e147. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3385

- Laferriere, K., & Crighton, E. J. (2017). “During pregnancy would have been a good time to get that information”: mothers’ concerns and information needs regarding environmental health risks to their children. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education, 55(2), 96-105. https://doi.org/10.1080/14635240.2016.1242376

- Lau, Y., Cheng, L. J., Chi, C., Tsai, C., Ong, K. W., Ho-Lim, S. S. T., Wang, W., & Tan, K.-L. (2018). Development of a healthy lifestyle mobile app for overweight pregnant women: qualitative study. JMIR Mhealth And Uhealth, 6(4), e91-e91. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.9718

- Lau, Y. K., Cassidy, T., Hacking, D., Brittain, K., Haricharan, H. J., & Heap, M. (2014). Antenatal health promotion via short message service at a midwife obstetrics unit in South Africa: a mixed methods study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14, article 284. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-284

- Lindgren, P., Stadin, M., Blomberg, I., Nordin, K., Sahlgren, H., & Ingvoldstad Malmgren, C. (2017). Information about first-trimester screening and self-reported distress among pregnant women and partners - comparing two methods of information giving in Sweden. Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 96(10), 1243-1250. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13195

- Liu, R.-L. (2004). Inquiry-bounded mining of imprecise data for adaptive information monitoring. Applied Artificial Intelligence, 18(7), 631-650. https://doi.org/10.1080/08839510490483288

- Lomazzi, M., Borisch, B., & Laaser, U. (2014). The millennium development goals: experiences, achievements and what’s next. Global Health Action, 7, article 23695. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.23695

- Lupton, D., & Pedersen, S. (2016). An Australian survey of women’s use of pregnancy and parenting apps. Women and Birth, 29(4), 368-375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2016.01.008

- Mahesh, G., & Gupta, D. K. (2008). Changing paradigm in journals based current awareness services in libraries. Information Services and Use, 28(1), 59-65. https://doi.org/10.3233/ISU-2008-0555

- Marko, K. I., Krapf, J. M., Meltzer, A. C., Oh, J., Ganju, N., Martinez, A. G., Sheth, S. G., & Gaba, N. D. (2016). Testing the feasibility of remote patient monitoring in prenatal care using a mobile app and connected devices: a prospective observational trial. JMIR Research Protocols, 5(4), e200. https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.6167

- McDonald, S. D., Sword, W., Eryuzlu, L. E., & Biringer, A. B. (2014). A qualitative descriptive study of the group prenatal care experience: perceptions of women with low-risk pregnancies and their midwives. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14, article 334. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-334

- McKenzie, P. J. (2004). Positioning theory and the negotiation of information needs in a clinical midwifery setting. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 55(8), 685-694. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20002

- McKenzie, P. J. (2003). A model of information practices in accounts of everyday-life information seeking. Journal of Documentation, 59(1), 19-40. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410310457993

- Moodley, J., Fawcus, S., & Pattinson, R. (2018). Improvements in maternal mortality in South Africa. South African Medical Journal, 108(3), 4-8.

- Moosa, S., & Gibbs, A. (2014). A focus group study on primary health care in Johannesburg health district: “We are just pushing numbers.” South African Family Practice, 56(2), 147-152. https://doi.org/10.1080/20786204.2014.10855353

- Mu, C. (2011). The impact of new technologies on current awareness tools in academic libraries. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 51(2), 92-97. https://doi.org/10.5860/rusq.51n2.92

- Mushwana, L., Monareng, L., Richter, S., & Muller, H. (2015). Factors influencing the adolescent pregnancy rate in the Greater Giyani municipality, Limpopo province – South Africa. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences, 2, 10-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2015.01.001

- Olliaro, P. L., Kuesel, A. C., & Reeder, J. C. (2015). A changing model for developing health products for poverty-related infectious diseases. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 9(1), e3379. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0003379

- Pereboom, M. T. R., Manniën, J., Spelten, E. R., Schellevis, F. G., & Hutton, E. K. (2013). Observational study to assess pregnant women’s knowledge and behaviour to prevent toxoplasmosis, listeriosis and cytomegalovirus. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 13(1), article 98. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-13-98

- Pickard, A. J. (2013). Research methods in information (2nd ed.). Neal-Schuman. http://dx.doi.org/10.29085/9781783300235

- Plutzer, K., & Keirse, M. J. N. C. (2012). Effect of motherhood on women’s preferences for sources of health information: a prospective cohort study. Journal of Community Health, 37(4), 799-803. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-011-9513-0

- Robinson, J. R., Anders, S. H., Novak, L. L., Simpson, C. L., Holroyd, L. E., Bennett, K. A., & Jackson, G. P. (2018). Consumer health-related needs of pregnant women and their caregivers. JAMIA Open, 1(1), 57-66. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamiaopen/ooy018

- Saldaña, J. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage Publications.

- Savolainen, R. (1995). Everyday life information seeking: approaching information seeking in the context of “way of life”. Library & Information Science Research, 17(3), 259-294. https://doi.org/10.1016/0740-8188(95)90048-9

- Sedrati, H., Nejjari, C., Chaqsare, S., & Ghazal, H. (2016). Mental and physical mobile health apps: review. Procedia Computer Science, 100, 900-906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2016.09.241

- Sharifi, M., Amiri-Farahani, L., Haghani, S., & Hasanpoor-Azghady, S. B. (2020). Information needs during pregnancy and its associated factors in Afghan pregnant migrant women in Iran. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health, 11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150132720905949

- Song, H., Cramer, E. M., McRoy, S., & May, A. (2013). Information needs, seeking behaviours and support among low-income expectant women. Women and Health, 53(8), 824-842. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2013.831019

- Tan, S. S.-L., & Goonawardene, N. (2017). Internet health information seeking and the patient-physician relationship: a systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(1), e9. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5729

- United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. (2019). Maternal and newborn health. https://www.unicef.org/health/maternal-and-newborn-health (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20210510165309/https://www.unicef.org/health/maternal-and-newborn-health)

- Waring, M. E., Moore Simas, T. A., Xiao, R. S., Lombardini, L. M., Allison, J. J., Rosal, M. C., & Pagoto, S. L. (2014). Pregnant women’s interest in a website or mobile application for healthy gestational weight gain. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare, 5(4), 182-184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2014.05.002

- Wilson, P. (1977). Public knowledge, private ignorance. Greenwood Press.

- Wong, V. W. Y., Fong, D. Y. T., & Tarrant, M. (2014). Brief education to increase uptake of influenza vaccine among pregnant women: a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14, article 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-19

- Yeoman, A. (2010). Applying McKenzie's model of information practices in everyday life information seeking in the context of the menopause transition. Information Research, 15(4), paper 444. http://www.informationr.net/ir/15-4/paper444.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200810005844/http://informationr.net/ir///15-4/paper444.html)

- Zelop, C. (2018). Introducing a new series on maternal mortality: with death rates rising, ob/gyns must dedicate themselves to protecting each mother. Contemporary OB/GYN, 63(1), 8-11.

- Zhu, C., Zeng, R., Zhang, W., Evans, R., & He, R. (2019). Pregnancy-related information seeking and sharing in the social media era among expectant mothers: qualitative study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(12), e13694. https://doi.org/10.2196/13694

How to cite this paper

Appendices

APPENDIX A: QUESTIONNAIRE

Questionnaire on information needs, information seeking and the need to monitor new information during pregnancy

This is an exploratory study to identify the information needs of pregnant women and their interest in monitoring new information on pregnancy and other issues related to their situation as expecting mothers. The findings will be used to make recommendations on means of information monitoring and current awareness services relevant to pregnant mothers.

The researcher will be available to deal with questions at the time when participants complete the questionnaire. She will also complete questionnaires on behalf of participants, if necessary.

Researcher: Olubukola M. Akanbi (Masters student, Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria, South Africa); +1 2405281043; olubukola_ogundele@yahoo.com

Supervisor: Prof Ina Fourie (Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria); (012) 420-5216; ina.fourie@up.ac.za

SECTION A: PERSONAL INFORMATION AND INFORMATION RELATED TO PREGNANCY

(1) Stage of pregnancy: (please tick only the most appropriate option)

| 1 - 10 weeks | |

| 11 - 20 weeks | |

| 21 - 30 weeks | |

| 31 - 40 weeks | |

| More than 40 weeks |

(2) Number of pregnancies: (please tick only the most appropriate option)

| This is my first pregnancy | |

| One full-term pregnancy | |

| Two full-term pregnancies | |

| Three full-term pregnancies | |

| Four full-term pregnancies | |

| Five or more full-term pregnancies | |

| I have been pregnant before, but it was not a full-term pregnancy | |

| Prefer not to say |

(3) Marital status: (please tick only the most appropriate option)

| Married | |

| Single | |

| Divorced | |

| Widow | |

| Prefer not to say |

| Other option you want to bring to our attention: | …………………………………… |

(4) Highest level of education: (please tick only the most appropriate option)

| Primary school – but not fully completed | |

| Primary school completed | |

| High school, but grade 12 not completed | |

| Grade 12 | |

| Diploma | |

| Bachelor’s degree | |

| Honours degree | |

| Master’s degree | |

| Doctoral degree | |

| Other post-high school qualification(s) |

(5) Approximate number of prenatal visits for the current pregnancy: (please tick only the most appropriate option)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | More than 6 |

(6) Reasons for prenatal visits: (please tick only the most appropriate option)

| Routine check-up | |

| Complications | |

| Obstetrics danger signs |

| Other (please specify) | …………………………………… |

SECTION B: PREFERENCES FOR INFORMATION SOURCES

(7) Please indicate the importance of the following information sources to you in your current pregnancy:

| Preference for information sources | Not important | Slightly important | Important | Very important |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friends | ||||

| Family members | ||||

| Magazines | ||||

| Search engines | ||||

| Electronic newsletters | ||||

| Brochures | ||||

| Pamphlets | ||||

| Bulletins | ||||

| Healthcare providers | ||||

| Blogs | ||||

| Text messages (SMS) | ||||

| Books | ||||

| Internet | ||||

| Social networks | ||||

| Discussion groups (online forums) | ||||

| Television programmes | ||||

| Radio programmes | ||||

| Audio-visual materials | ||||

| Are there any other information sources that are important to you and that you are willing to mention to us? (Please specify). | ||||

SECTION C: INFORMATION SEEKING AND FACTORS AFFECTING INFORMATION SEEKING

(8) Please specify the chances of the following ways of information seeking happening during your current pregnancy:

| Active seeking (turning to sources for a specific purpose). | Already happened | Highly likely | Likely | Unlikely | Highly unlikely |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I will ask my healthcare provider(s) for pregnancy-related information. | |||||

| I will make a list of questions prior to my appointment with my healthcare provider(s). | |||||

| I will search for information by buying pregnancy-related information materials or publications. | |||||

| I will ask friends and family members for pregnancy-related information. | |||||

| Active scanning and browsing (turning to sources in the hope that you might find something of interest). | |||||

| I will browse through bookshelves in bookshops for pregnancy-related information. | |||||

| I will browse through bookshelves in libraries for pregnancy-related information. | |||||

| I will look around in the healthcare provider’s consulting rooms for pregnancy-related information. | |||||

| I will check in maternity centres for pregnancy-related information. | |||||

| I will look for information on pregnancy by flipping through information materials on pregnancy and related issues. | |||||

| I will browse the Internet for information on pregnancy and related issues. | |||||

| Non-directed monitoring of information (pursuing no specific goal). | |||||

| I might glance through magazines or newspapers for other purposes and then find pregnancy-related information. | |||||

| I could watch tv or listen to a radio programme, and then come across useful information on pregnancy. | |||||

| I might find pregnancy-related information in unfamiliar places and circumstances, e.g., seeing a mother pushing a double baby stroller. | |||||

| Directed monitoring (monitoring sources on an on-going bases for a specific purpose). | |||||

| I might subscribe to magazines or relevant publications on pregnancy. | |||||

| I might find pregnancy-related information through e-mail alerts. | |||||

| I could receive pregnancy-related information by monitoring the Internet websites. | |||||

| By proxy (getting information through the help of somebody else searching on your behalf). | |||||

| I will ask other people to search on my behalf for pregnancy-related information. | |||||

| I will rely on other people to refer me to information or people with information. | |||||

| Family members, friends, colleagues and associates scan various pregnancy-related information sources on my behalf and bring information to my attention. | |||||

| Passive seeking and accidental encountering (getting information without asking). | |||||

| I will get information and advice when people see my protruded stomach. | |||||

| I will pick up pregnancy-related information from other people’s discussions, e.g., In health care provider’s consulting room, at the hairdresser. | |||||

| I will pick up pregnancy-related information when friends and family bring pregnancy issues to my attention. |

SECTION D: DEVICES FOR ACCESSING INFORMATION

(9) Please tick all devices that you use for accessing information.

| Mobiles/cell phones/smartphones | |

| Tablets | |

| Proxy (asking other people to use their devices to search on your behalf). | |

| Desktop or laptop | |

| Other (please specify). |

APPENDIX B: INTERVIEW SCHEDULE

Current awareness services and information monitoring supporting the information behaviour of pregnant women

Schedule of topics for interviews with pregnant women (this schedule will also be used to guide the focus group interviews)

This is an exploratory study to identify the information needs of pregnant women and their interests in monitoring new information on pregnancy and other issues related to their situation as expecting mothers. Findings will be used to make recommendations on means of information monitoring and current awareness services relevant to pregnant mothers, and on the theory of information behaviour.

Researcher: Olubukola M. (Akanbi Masters student, Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria, South Africa); +1 2405281043; olubukola_ogundele@yahoo.com

Supervisor: Prof Ina Fourie (Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria); (012) 420-5216; ina.fourie@up.ac.za

Interview topics

- 1) Discussion of ways of staying abreast with pregnancy-related information

- a. Ways and means they have used up to the time of the interview

- b. Opinion on other ways suggested by the researcher