Exploring the socio-economic determinants of health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet in Turkey

Murat Konca, Şenol Demirci, Cuma Çakmak, and Özgür Uğurluoğlu

Introduction. The digitisation of health care services has popularised Internet based health information-seeking behaviour. This research investigates the connection between the socio-demographic and economic characteristics of Turkish individuals and their online health information-seeking behaviour.

Method. The study method was binary logistic regression on existing social datasets.

Analysis. This study considered the dataset obtained from a survey conducted by the Turkish Statistical Institute. The effects of age, sex, education level, working status, location, and frequency of Internet use on the health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet were examined.

Results. Health information was sought more frequently by women than men, by people aged 26–35 and 36–45 than by those 25 and below, by people with higher income, and by those with higher levels of education. Health information searches were also conducted more often in developed regions than in less-developed regions. The habit of seeking health information online was also found to be more common among those who use the Internet more frequently.

Conclusions. The current paper examined the effects of socio-demographic and economic characteristics of Turkish individuals on their online health information-seeking behaviour and contributes new insights on this behaviour.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper930

Introduction

Technology and the rapid spread of digitalisation due to technology have caused significant transformations in public health and the delivery of health care services (Weaver, et al., 2009). The more frequent use of the term e-health, which means bringing together those who demand and provide health care services in a digital environment without physically coming together, is important in capturing this digitalisation of health care services (Haluza, et al., 2017; Matusitz and Breen, 2007), resulting in health information-seeking behaviour also starting to become digital.

Health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet describes the efforts of individuals to obtain information about their health status, risks, diseases, and health-protective behaviour (Jacobs, et al., 2017; Lambert and Loiselle, 2007; Mills and Todorova, 2016). Although a wide variety of sources can provide information to individuals on these issues, the Internet tends to be a prominent source of information (Jiang and Liu, 2020). Given the increasing number of people using the Internet and the websites providing information on health care services, as well as the Internet’s accessibility to all members of society seeking medical information (enabling fast access to information as well as access to electronic medical records and even direct communication with physicians), the Internet provides convenience for some sensitive health problems about which individuals may feel shy or embarrassed when consulting physicians (i.e. the Internet provides anonymity) and thus tends to take precedence over other methods of health information-seeking behaviour (Chung, 2013; Gutierrez, et al., 2014; Jacobs, et al., 2017; Lee, 2008; Te Poel, et al., 2016; Zhao, 2009).

Besides being a basic resource for seeking health information, the Internet also contributes to reducing health inequalities (Percheski and Hargittai, 2011). Knowledge is one of the main sources of health inequalities, and in terms of health, it is not possible to say that all segments of society have the same level of knowledge (Link and Phelan, 1995). Because the Internet is a resource that may have significant benefits in reducing the inequalities of knowledge related to health, it also contributes to reducing health inequalities (Percheski and Hargittai, 2011).

This study dealt with the determinants of the behaviour of seeking health information on the Internet among Turkish individuals. Although there are national studies like this in the literature, those studies were carried out in limited samples and do not represent the whole country. Accordingly, there appears to be a need for studies of interest to the whole country. This study therefore examined the connection between the socio-demographic and socio-economic characteristics of Turkish people and health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet by examining the association of the socio-demographic and socio-economic variables and health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet among individuals to determine the impact of these factors on such behaviour. Another important motivation for this study was to reveal whether the effects of these factors changed over the study years. Data from the Survey on the Usage of Information Technologies in Households for the years 2013, 2015, 2017, and 2019 were used in the current study, and we sought to determine if there were any changes in the study years of the health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet among Turkish individuals. This study provides important information to policymakers in Turkey about such behaviour. In addition, this study is also important on the international level and may provide a roadmap to the variables and approaches for future international studies dealing with health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet.

Literature review

As a result of the increasing use of the Internet and the perception that the Internet is an important source of health information, the factors that may affect the health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet have attracted research attention. There appears to be a wide range of studies on the determinants of such behaviour. For example, Zhao (2009) studied whether parental education level affected the health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet of adolescents in the United States. The results indicated that such behaviour was more frequent among adolescents whose parents have relatively lower education levels, and this was explained as the adolescents seeking health information on behalf of their parents. In their study of 700 Americans, Beaudoin and Hong (2011) compared the use of the Internet, television, and newspapers as sources of health information based on users’ age, sex, income, and education level. According to their results, health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet was seen more frequently in youth and women, and, as the income and education level increased, such behaviour also increased. These findings were explained as due to youth, women, and individuals with higher education and income levels being more likely to use the Internet. Percheski and Hargittai (2011) studied the determinants of health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet of 1,060 first-year students studying at a public university in the United States Midwest. According to their results, more girls than boys sought out health information on the Internet. Proficiency of Internet use and living with parents also increased such behaviour. Haluza, et al. (2017), studied the effect of age, sex, education level, level of trust in health information on the Internet, and communication level between a patient and a physician on health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet. According to their results in a study of 562 people in Austria, the health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet differed according to sex, level of trust in health information on the Internet, and communication level between physician and patient. Jacobs, et al. (2017), assessed the impact of age, race, education level, sex, state of health, perception of health, cancer cases in the family, and Internet use proficiency among US adults on the health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet. According to their results, age, education level, and Internet use proficiency affected such behaviour.

As can be seen from the studies above, health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet is associated with various socio-economic and socio-demographic factors. There are, however, only a limited number of studies on this topic conducted in Turkey. For example, in their study with 506 students studying at two universities in Turkey, Güzel and Kurtuldu (2018) investigated whether health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet varied according to sex. They found that female students were more likely to use the Internet to seek health information. In their study of 420 students studying at a university in Turkey, Gencer, et al. (2019), studied the levels of student access to health resources on social media and found that participants who were relatively younger and spent more time on social media were more likely to search for health information on social media. Both studies were conducted with limited samples in universities, so it is difficult to reach a national generalisation from these results.

Methods

Data and research variables

The data for the present study were obtained from the Survey on the Usage of Information Technologies in Households conducted by the Turkish Statistical Institute [TUIK] on a representative sample in Turkey (individuals aged 16–74). This survey has been carried out every year since 2004 to provide information about household and individual Internet use (TUIK, 2019). The question related to Internet use in the survey is: ‘What activities have you used the Internet for in the last three months?’ This is a closed-ended question with thirteen categories (including email, listening to music, social media, Internet banking, scheduling a doctor’s appointment, shopping), and the answers can be either ‘yes’ or ‘no’ for all categories. Participants can answer ‘yes’ for more than one category. The tenth category is ‘to search for health information’. For the purposes of this study, individuals answering ‘yes’ to this category have searched for health information on the Internet, while individuals answering ‘no’ have not.

Because this study aimed to evaluate the impact of socio-demographic and socio-economic features on health information-seeking behaviour, this behaviour was identified as the dependent variable. Variables such as sex, age, education, marital status, occupation, race, Internet usage frequency, income, health status, perception of health, and residence in urban or rural areas are among the independent variables found to affect such behaviour in the literature (Beaudoin and Hong, 2011; Din, et al., 2019; Finney-Rutten, et al., 2019; Gutierrez, et al., 2014; Güzel and Kurtuldu, 2018; Haluza, et al., 2017; Jacobs, et al., 2017; Te Poel, et al., 2016; Tennant, et al., 2015). This study therefore used the following independent variables: sex; age; education; residential region (in the source survey, the cities in Turkey are classified according to Statistical Regional Units Classification Level 1 and divided into twelve regions); employment status; Internet usage frequency; and monthly household income. To evaluate the change in time, the Survey on the Usage of Information Technologies in Households data sets from 2013, 2015, 2017, and 2019 were used, and the required permissions for the use of the data were obtained from the TUIK.

Population and sample

The population in the current study consisted of individuals who participated in the Survey on the Usage of Information Technologies in Households in the years 2013, 2015, 2017, and 2019. The participants who did not answer the question regarding health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet were not included in the sample, and the study sample consists of individuals who answered either ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to the question regarding health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet. The number of people answering this question were 12,304 in 2013, 10,918 in 2015, 17,901 in 2017, and 20,316 in 2019.

Analysis

Regression analyses can be used to evaluate the impact the independent variables (sex, age, education, residence region, employment status, Internet usage frequency, and monthly household income) on the dependent variable (health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet). This is the best form of analysis when the dependent variable is categorical (Wright, 1995). Because respondents provided a categorical ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer for the dependent variable of this study, logistic regression analysis was used.

Results

The socio-demographic and socio-economic information regarding the participants is shown in Table 1. The ratio of the female participants, which was 39.3% in 2013, increased to 47.7% in 2019, but remained lower than the proportion of male participants for all the years. The ratio of participants under 25 constantly decreased and those aged 36–45 and 45 and over constantly increased over the years. Most of the participants were high school graduates in all years. The highest number of participants lived in Istanbul. The number of employed participants was higher than that for unemployed participants for all years except 2019. The average monthly income was around 2,308 Turkish Liras (TL) in 2013, and this increased to around 4,054 TL in 2019. Regarding Internet use frequency, the ratio of the participants who answered the question with almost every day increased over the years, and most of the participants claimed to use the Internet almost every day.

| 2013 | 2015 | 2017 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Women | 4841 (39.3) | 4683 (42.9) | 8265 (46.2) | 9689 (47.7) |

| Men | 7463 (60.7) | 6235 (57.1) | 9636 (53.8) | 10627 (52.3) |

| Age | ||||

| 25 age and under | 4357 (35.4) | 3203 (29.3) | 4748 (26.5) | 4562 (22.5) |

| Between 26-35 age | 3619 (29.4) | 3353 (30.7) | 4861 (27.2) | 5145 (25.3) |

| Between 36-45 age | 2620 (21.3) | 2518 (23.1) | 4525 (25.3) | 5189 (25.5) |

| 46 age and older | 1708 (13.9) | 1844 (16.9) | 3767 (21.0) | 5420 (26.7) |

| Education Level | ||||

| Didn't finish a school | 115 (0.9) | 146 (1.3) | 434 (2.4) | 681 (3.4) |

| Primary school | 1763 (14.3) | 1897 (17.4) | 3916 (21.9) | 5096 (25.1) |

| Secondary school | 3150 (25.6) | 2654 (24.3) | 4457 (24.9) | 4380 (21.6) |

| High school | 4050 (32.9) | 3279 (30.0) | 4814 (26.9) | 5187 (25.5) |

| Associate/Bachelor graduate | 2935 (23.9) | 2644 (24.2) | 3848 (21.5) | 4311 (21.2) |

| Postgraduate | 291 (2.4) | 298 (2.7) | 432 (2.4) | 661 (3.3) |

| Living Region | ||||

| Istanbul | 2146 (17.4) | 2054 (18.8) | 2882 (16.1) | 3171 (15.6) |

| West Marmara | 850 (6.9) | 670 (6.1) | 1077 (6.0) | 1176 (5.8) |

| East Marmara | 1380 (11.2) | 1102 (10.1) | 1757 (9.8) | 1856 (9.1) |

| Aegean | 1426 (11.6) | 1349 (12.4) | 2021 (11.3) | 2151 (10.6) |

| Mediterranean | 1128 (9.2) | 1079 (9.9) | 2015 (11.3) | 2191 (10.8) |

| West Anatolia | 1527 (12.4) | 1096 (10.0) | 1899 (10.6) | 2265 (11.1) |

| Middle Anatolia | 804 (6.5) | 713 (6.5) | 1216 (6.8) | 1471 (7.2) |

| West Blacksea | 762 (6.2) | 757 (6.9) | 1267 (7.1) | 1314 (6.5) |

| East Blacksea | 468 (3.8) | 476 (4.4) | 928 (5.2) | 923 (4.5) |

| Southeast Anatolia | 831 (6.8) | 740 (6.8) | 1274 (7.1) | 1534 (7.6) |

| Middle east Anatolia | 557 (4.5) | 629 (5.8) | 952 (5.3) | 1213 (6.0) |

| Northeast Anatolia | 425 (3.5) | 253 (2.3) | 613 (3.4) | 1051 (5.2) |

| Working Status | ||||

| Working | 6871 (55.8) | 6046 (55.4) | 9263 (51.7) | 10000 (49.2) |

| Not Working | 5433 (44.2) | 4872 (44.6) | 8638 (48.3) | 10316 (50.8) |

| Frequency of Internet Use | ||||

| Almost every day | 8354 (67.9) | 8421 (77.1) | 15504 (86.6) | 18209 (89.6) |

| At least once a week | 2896 (23.5) | 1832 (16.8) | 1224 (6.8) | 400 (2.0) |

| At least once a month | 1054 (8.6) | 665 (6.1) | 1173 (6.6) | 1707 (8.4) |

| Household Monthly Income (TL) | 2013 (x̄ ± S) | 2015 (x̄ ± S) | 2017 (x̄ ± S) | 2019 (x̄ ± S) |

| 2308 ± 3136 | 2652 ± 2201 | 3124 ± 2595 | 4054 ± 3548 | |

| Total Participants | 12304 (100) | 10918 (100) | 17901 (100) | 20316 (100) |

Looking at the health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet according to the years studied, 58.9% of the participants in 2013, 67.3% in 2015, 69.4% in 2017, and 68.7% in 2019 searched for health information on the Internet (Table 2).

| Seeking health information | 2013 | 2015 | 2017 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Yes | 7242 (58.9) | 7345 (67.3) | 12423 (69.4) | 13952 (68.7) |

| No | 5062 (41.1) | 3573 (32.7) | 5478 (30.6) | 6364 (31.3) |

| Total Participants | 12304 (100) | 10918 (100) | 17901 (100) | 20316 (100) |

The results of the logistic regression analysis evaluating the impact of participants’ socio-demographic and socio-economic features on their health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet for the years of 2013, 2015, 2017, and 2019 are given in Table 3. The Nagelkerke’s R² explanatory coefficients are 0.20 for 2013, 0.22 for 2015, 0.18 for 2017, and 0.24 for 2019. The Hosmer and Lemeshow values are statistically significant in all years.

| 2013 | 2015 | 2017 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | Odds ratio | Odds ratio | Odds ratio | |

| Sex | ||||

| Women | 2.36 *** | 2.02 *** | 1.77 *** | 1.60 *** |

| Men (Reference) | ||||

| Age | ||||

| 25 age and under (Reference) | ||||

| Between 26-35 age | 1.86 *** | 1.78 *** | 1.68 *** | 1.78 *** |

| Between 36-45 age | 1.88 *** | 1.77 *** | 1.59 *** | 1.50 *** |

| 46 age and older | 1.64 *** | 1.60 *** | 1.07 | 0.90 |

| Household Monthly Income (TL) | 1.00 | 1.00 *** | 1.00 *** | 1.00 *** |

| Education Level | ||||

| Didn't finish a school (Reference) | ||||

| Primary school | 1.51 | 1.70 ** | 1.63 *** | 2.16 *** |

| Secondary school | 1.63 * | 1.94 ** | 2.37 *** | 3.51 *** |

| High school | 2.78 *** | 3.86 *** | 4.26 *** | 6.07 *** |

| Associate/Bachelor graduate | 4.35 *** | 5.84 *** | 6.70 *** | 12.01 *** |

| Postgraduate | 5.65 *** | 6.30 *** | 7.55 *** | 12.47 *** |

| Living Region | ||||

| Istanbul | 1.73 *** | 1.91 *** | 2.02 *** | 1.96 *** |

| West Marmara | 1.31 * | 2.14 *** | 1.39 ** | 1.91 *** |

| East Marmara | 1.84 *** | 1.93 *** | 2.16 *** | 3.29 *** |

| Aegean | 1.38 ** | 1.38 * | 1.19 | 1.66 *** |

| Mediterranean | 1.24 | 1.51 ** | 1.45 *** | 1.61 *** |

| West Anatolia | 1.59 *** | 1.96 *** | 1.81 *** | 1.86 *** |

| Middle Anatolia | 1.28 | 1.55 ** | 1.26 * | 1.35 ** |

| West Blacksea | 1.45 ** | 2.09 *** | 1.71 *** | 1.69 *** |

| East Blacksea | 1.28 | 1.98 *** | 1.78 *** | 1.29 * |

| Southeast Anatolia | 1.14 | 1.23 | 2.19 *** | 1.60 *** |

| Middle east Anatolia | 1.69 *** | 2.70 *** | 2.13 *** | 1.98 *** |

| Northeast Anatolia (Reference) | ||||

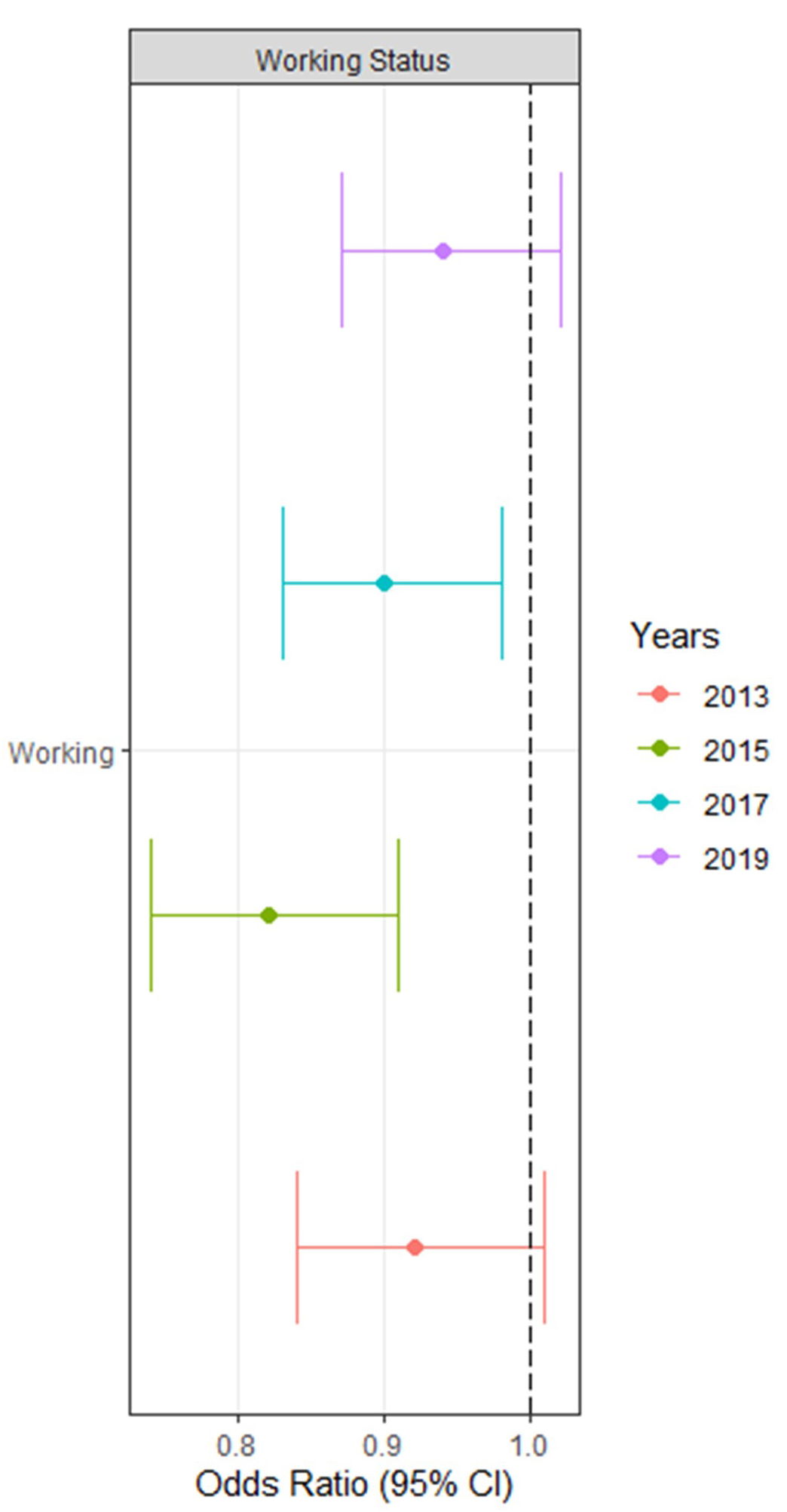

| Working Status | ||||

| Working | 0.92 | 0.82 *** | 0.90 * | 0.94 |

| Not Working (Reference) | ||||

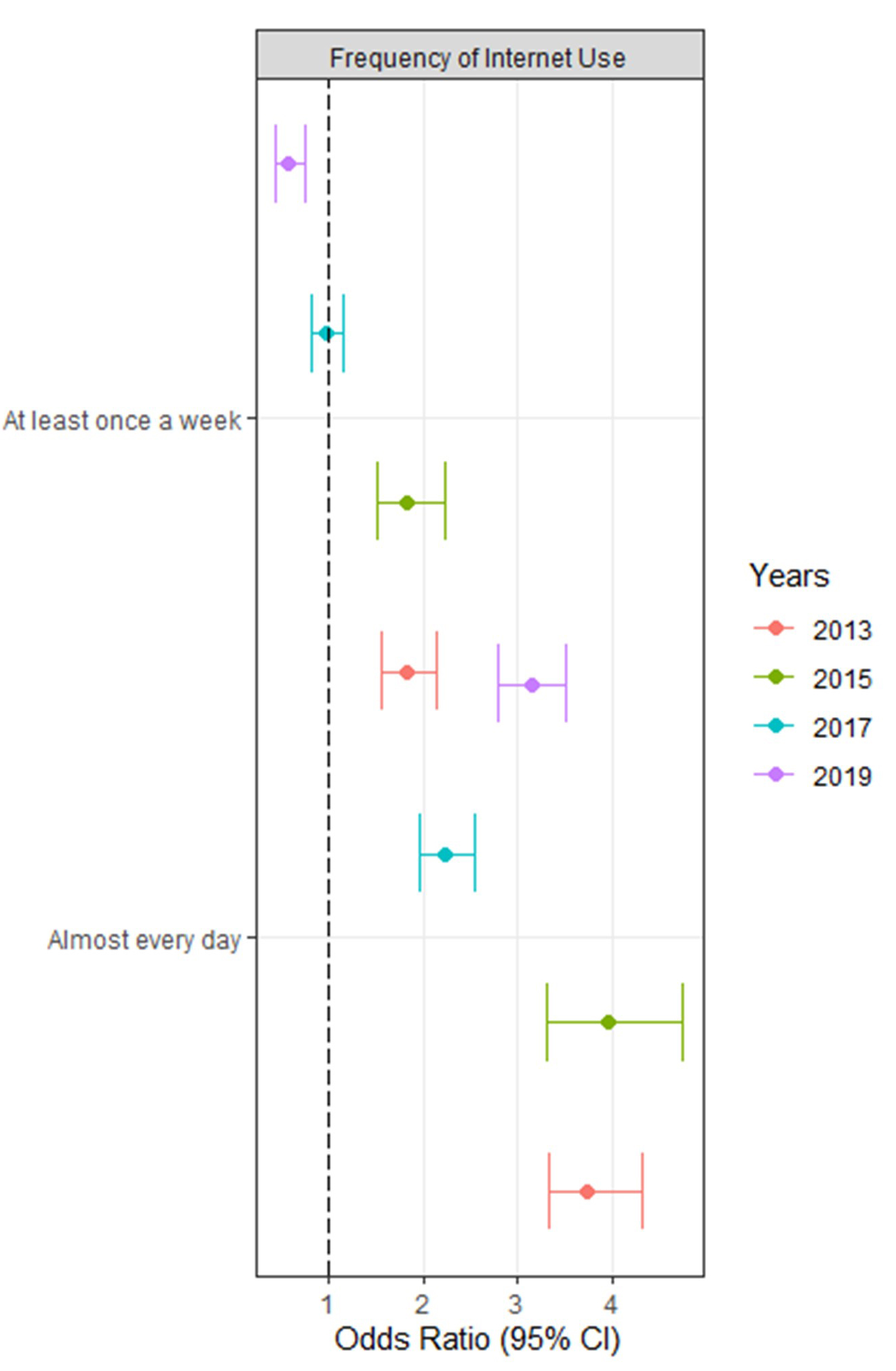

| Frequency of Internet Use | ||||

| Almost every day | 3.72 *** | 3.96 *** | 2.23 *** | 3.14 *** |

| At least once a week | 1.82 *** | 1.83 *** | 0.97 | 0.57 *** |

| At least once a month (Reference) | ||||

| Constant | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.06 |

| Nagelkerke R² | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.24 |

| Hosmer and Lemeshow χ2(df) | 8.22 (8) | 13.94 (8) | 10.24 (8) | 6.56 (8) |

| Note: ***P-value < 0.001, **P-value < 0.01, *P-value < 0.05 | ||||

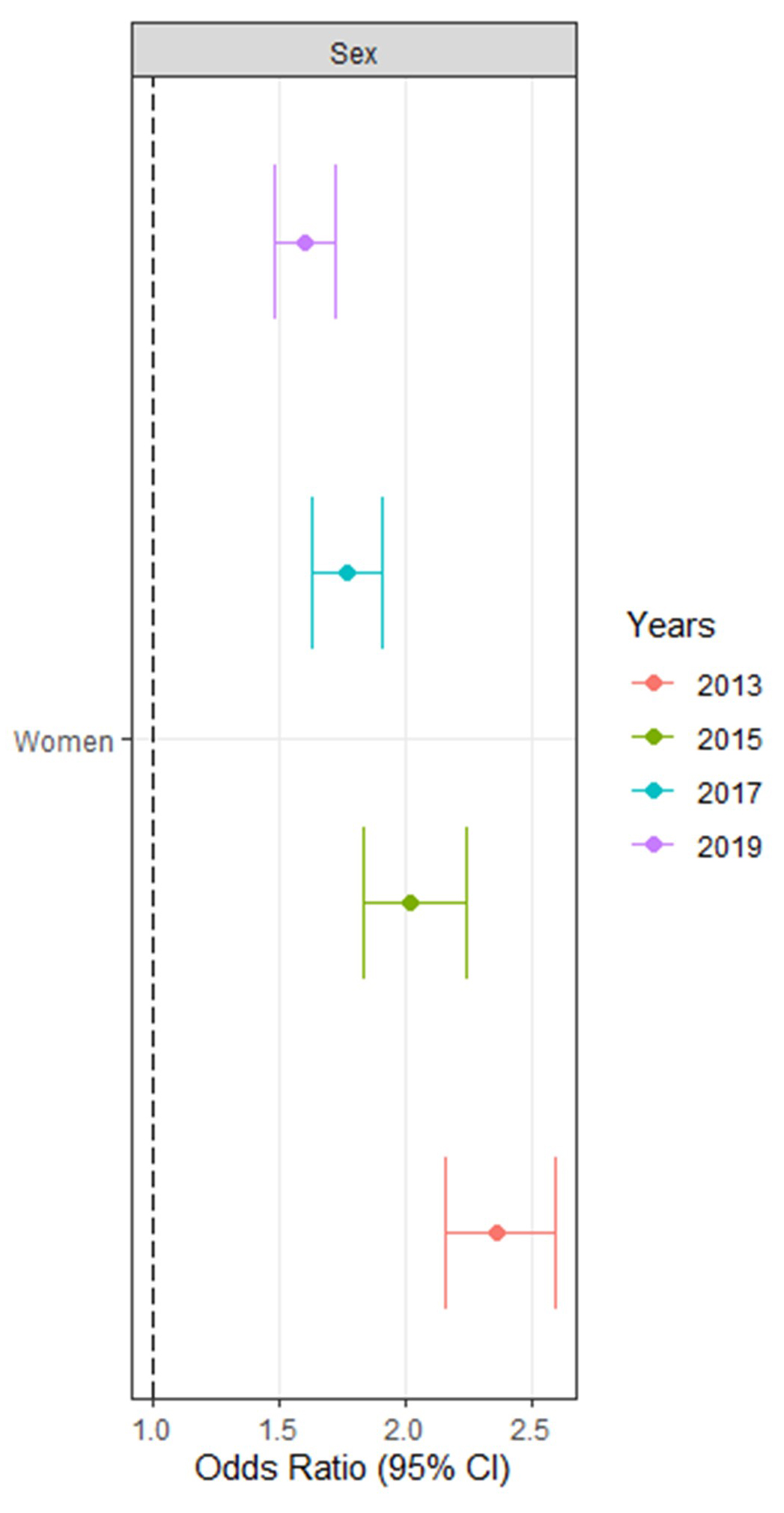

When the results regarding participant sex were analysed, it was determined that female participants were more likely to search for more health information on the Internet in all years compared to males, and these results were statistically significant. However, while women searched for health information on the Internet 2.36 times more than men, this coefficient decreased over the years, reaching 1.60 in 2019.

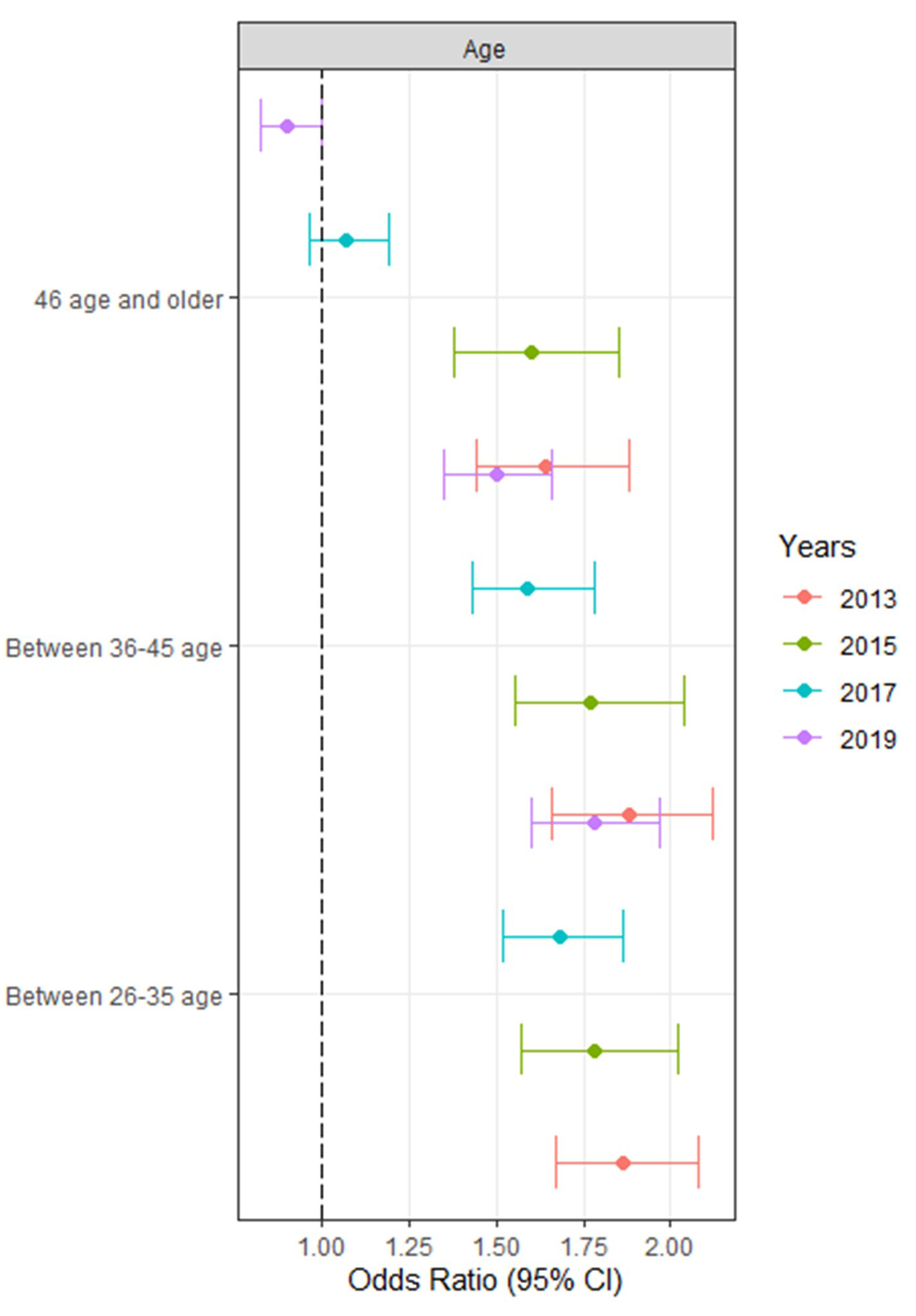

When the age variable was examined and compared with the reference ages of 25 and under, participants between 26 and 35 and 36 and 45 searched for more health information on the Internet in all years, and those aged 46 and over searched the most in 2013 and 2015, and these results were also statistically significant. The odds ratio difference between the reference group of age 25 and under and the other age groups was determined to decrease over the years.

Looking at the impact of participant income on health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet, it appeared that as participant income increased over the years, the health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet also increased, except for 2013.

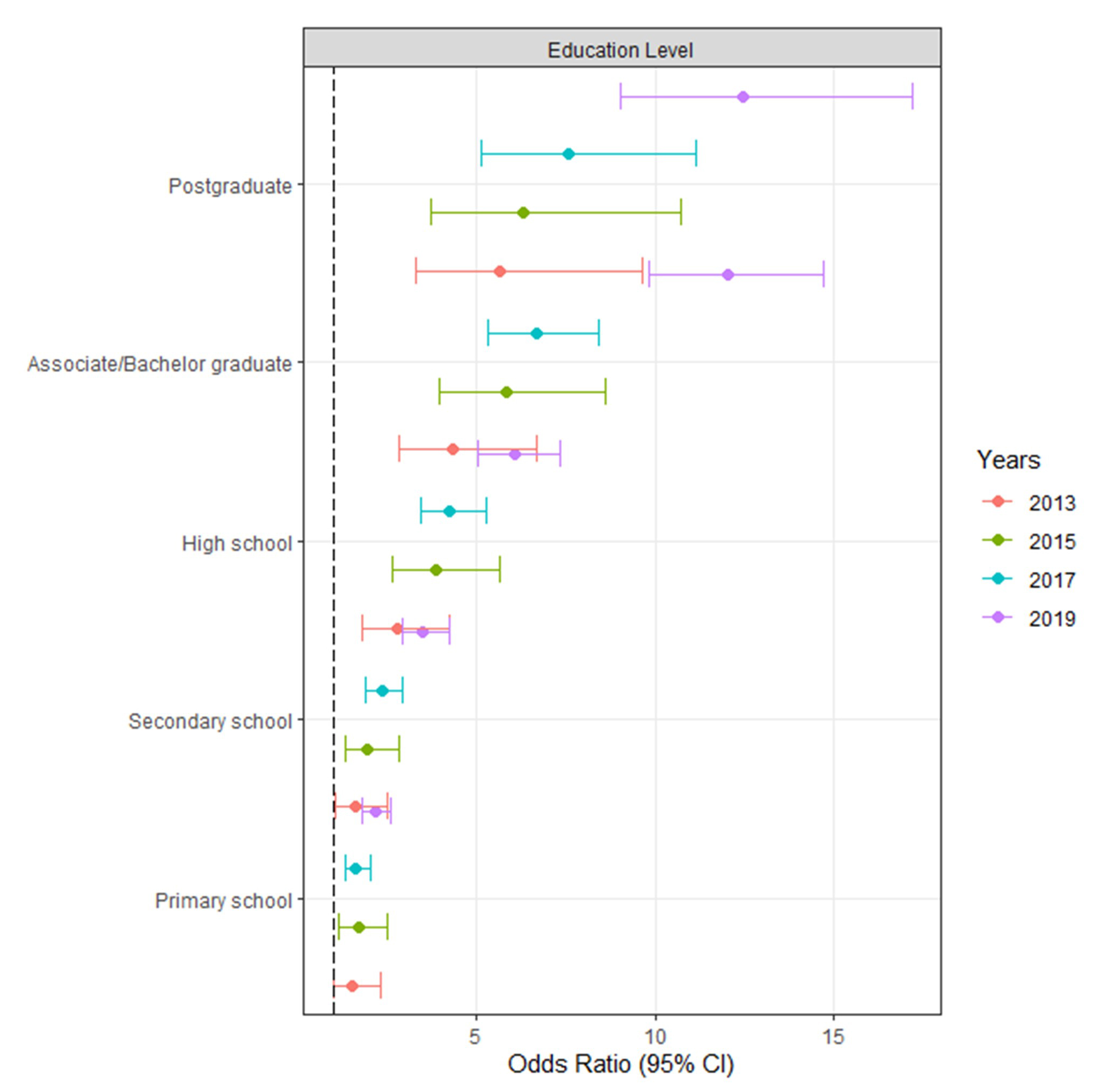

In terms of education, it was found that primary school (except for 2013), secondary school, high school, associate degree, and undergraduate graduates were more likely to search for health information on the Internet for all years compared to the reference group of non-degree holding participants, and these results were statistically significant. After a year-wise comparison, the odds ratio difference between the reference group and the other groups appeared to increase every year.

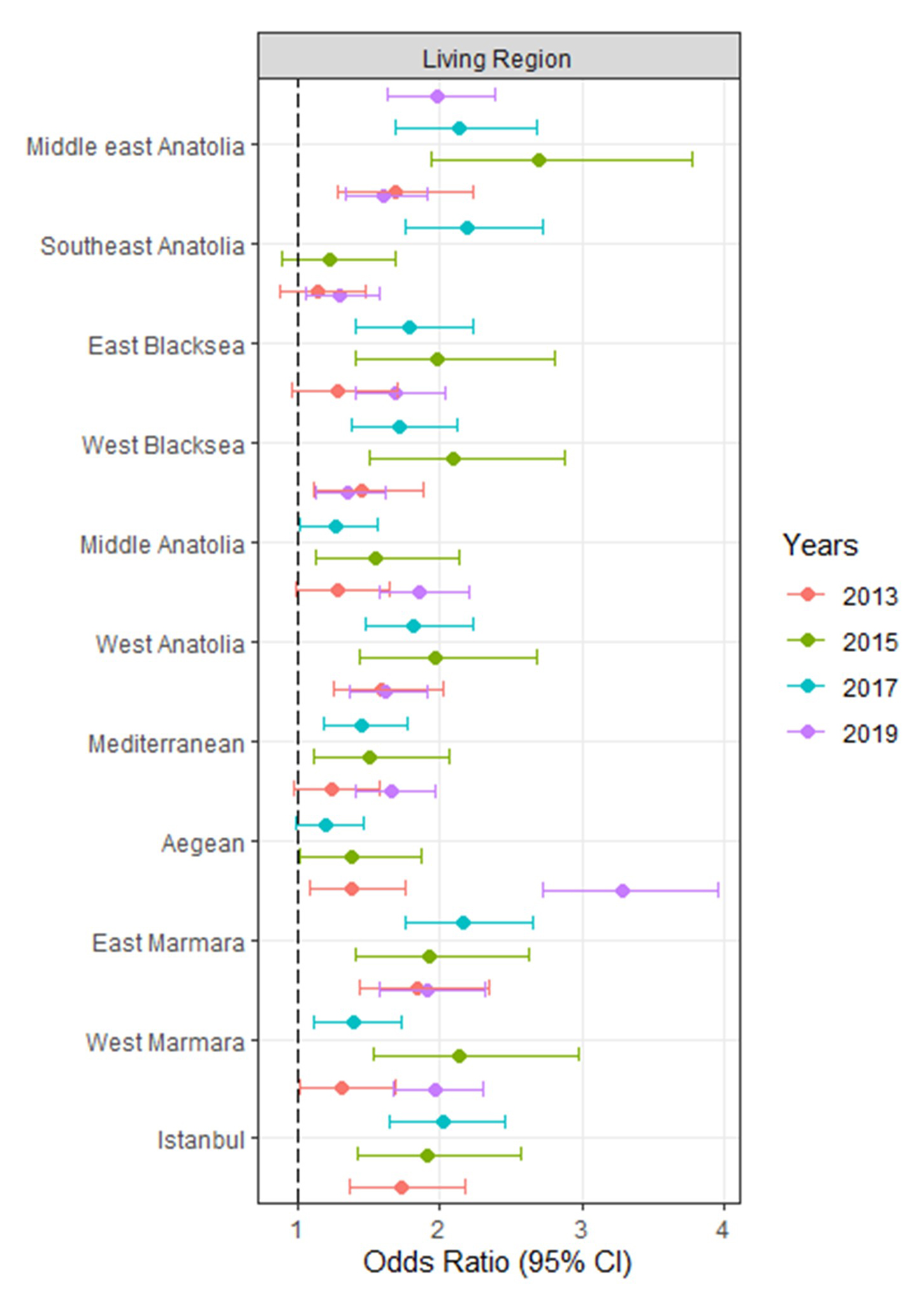

When the effect of the region of residence was evaluated, participants living in Istanbul, West Marmara, East Marmara, West Anatolia, West Black Sea, and Middle East Anatolia appeared to search for more health information on the Internet in all years, and these results were statistically significant. Participants in the Aegean region (except for 2017), participants in the Mediterranean, Central Anatolia and Eastern Black Sea regions (except for 2013), and participants in south-eastern Anatolia (except for 2013 and 2015) searched for more health information on the Internet than participants in the Northeast Anatolia region, which was the reference region, and these results were statistically significant. There was no regular increase in the odds ratio difference between the reference region and other regions (except for East Marmara) by year.

When employment status was analysed, the reference group, which was the unemployed (2015 odds ratio=0.82 and 2017 odds ratio=0.90), searched for more health information on the Internet than the employed, and these results were statistically significant.

When the effect of frequency of Internet use on the health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet was analysed, it appeared that those who used the Internet almost every day searched for health information 3.72 times more in 2013, 3.96 times more in 2015, 2.23 times more in 2017, and 3.14 times more in 2019 than those who used the Internet at least once a month, and these results were statistically significant. Participants using the Internet at least once a week searched for health information on the Internet 1.82 times more in 2013 and 1.83 times more in 2015 compared to the reference group. Participants using the Internet at least once a week (odds ratio=0.57) were found to search for health information on the Internet less in 2019 when compared with the reference group. There was no regular increase in the odds ratio difference between the reference group and other groups by year.

The study results are visually represented in Figure 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Discussion of the findings and implications

The Internet has revolutionized the way information is shared and accessed. Sharing and accessing information is easier now than ever before, at almost any time of the day with the help of modern search engines and social network access through devices such as smartphones and tablet or laptop computers (Tonsaker, et al., 2014). In Turkey, 91% of households have Internet access, and 80% of individuals aged 16–74 years use the Internet actively (TUIK, 2020). The Internet can thus be identified as an important information source for both patients and healthy people (Tonsaker, et al., 2014). Individuals with health problems today thus tend to search for health information on the Internet. There are many factors that affect health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet. This study sought to reveal the factors affecting health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet in Turkey and how these have changed over the years.

Many factors were identified. The tendency to search for health information on the Internet is higher among women than men, and people who are search for health information on the Internet tend to be more educated and have a higher income (Higgins, et al., 2011). According to the findings of this study, sex has a statistically significant effect on health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet, as women are more likely to search for health-related information on the Internet. Compared to men, women benefit from health services more (Boccolini and Junior, 2016). The effect of sex on receiving health services is also noteworthy, as women are more selective in their primary and secondary healthcare services, and they also refer to health care services more than men (Glynn, et al., 2011). Andreassen, et al. (2007), found that women use the Internet for health problems more than men, and motherhood status could be viewed as a reason for this behaviour. The fact that women have more responsibilities caring for children while breastfeeding than men, and children in these periods are more likely to become unwell makes the Internet a source of rapid information for mothers (Folayan, et al., 2017). Based on these findings, the fact that women search for health information on the Internet more than men can be associated with women’s cultural roles. According to the results of this study, while women searched for health information on the Internet 2.36 times more than men in 2013, this rate dropped to 1.60 in 2019, and a decrease was detected over the years. This decreasing trend may be associated with the fact that women have started to integrate more into business life and do not have as much free time as they balance motherhood and work-life roles. More research is needed to understand this trend better.

The age variable is also associated with health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet, as people engaging in such behaviour tend to be middle-aged or older (Cotten and Gupta, 2004). In this study, when the age variable was examined and compared with the reference ages of 25 and under, participants between 26 and 35 and 36 and 45 were more likely to search for health information on the Internet in all years and those 46 and over did so in 2013 and 2015; these findings are consistent with the literature. Some studies have also shown that health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet increased more in older age groups than other groups (Campbell and Nolfi, 2005; Ferguson, 2000). According to a study of 72,806 women aged 65 and older, 59% of participants used the Internet to search for health information (Sedrak, et al., 2020). Health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet might have some effect on the quality of life for people middle-aged and older. According to Jamal, et al. (2015), older individuals are at a higher risk of developing chronic diseases than those in other adult age groups. For this reason, getting information about health from the Internet quickly and easily – especially on chronic diseases – might affect the quality of life of elderly people. Elderly people who have higher levels of education and income, who use many medications, and who have more than one concomitant illness (comorbidity) also tend to use digital technologies more (Levine, et al., 2016). Elderly individuals who have problems accessing health care services also tend to be more likely to search for health information on the Internet (Waring, et al., 2018).

Considering the effect of participant income on health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet, such behaviour increased as income increased in all years except for 2013. Income can be evaluated as a significant factor in buying technological devices and accessing the Internet. It is stated in the literature that individuals with low socio-economic status have limited opportunities for high-speed, private, home-based Internet access. This socio-demographic difference prevents some individuals from accessing sufficient online health information (Li, et al., 2016). Alkhatlan, et al. (2018), found that the ratio of participants getting information about health from the Internet notably increased as the socio-economic level and monthly family income increases. Similarly, Nangsangna and Vroom (2019) found that average monthly income was significantly related to use of the Internet to seek health information. Income thus appears to be an important factor that makes health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet easier.

The effect of education, another variable examined within the scope of this study, on health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet was examined. Participants who had completed primary school (except for 2013), secondary school, high school, associate degree, and undergraduate degrees tended to search for more health information on the Internet for all years compared to the reference group of participants without any degree. After the literature review, similar results can be seen, revealing that, as education level increases, the level of searching for health information on the Internet increases (Alkhatlan, et al., 2018; Andreassen, et al., 2007; Chu, et al., 2017; Hesse, et al., 2005; Lee, et al., 2014; Sedrak, et al., 2020). The level of technological literacy, health literacy, and health awareness appears to be directly proportional to education level (Hesse, et al., 2005; Lee, et al., 2014). Low levels of education may cause lower health awareness and technological literacy, leading to less health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet.

Regional development level is another factor affecting health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet. In their study, Chen and Zhu (2016) indicated that individuals with psychological problems who migrated from rural areas to cities were more likely to access online health information and get help from the Internet. In another 2016 study, Koo, et al. 2016, found that male Internet users living in a city centre searched for health information on the Internet more. Besides the rural-urban distinction, the regional development levels of a country can also influence the health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet. In a study conducted by Gallagher, et al. (2008), such behaviour occurred more in developed regions than in underdeveloped regions. Within the scope of this study, whether there was a relationship between interregional development status and the health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet was examined. In this context, north-eastern Anatolia was taken as the reference region, and comparisons were made with other regions accordingly. North-eastern Anatolia is a mountainous region with low population density and a climate with harsh winters, and these characteristics can hinder Internet access. In this context, it was detected that participants living in other regions were more likely to search for health information on the Internet than those in North-eastern Anatolia – that is, in Istanbul, West Marmara, East Marmara, West Anatolia, West Black Sea, and Middle East Anatolia in all years, in the Aegean except for 2017, in the Mediterranean, Middle Anatolia, and East Black Sea except for 2013, and in Southeast Anatolia except for 2013 and 2015. These other regions have higher populations and better climate and land, so technology and Internet infrastructure are more widespread. Within the scope of incentive region-based policies, the Marmara Region, which is the most developed in Turkey, has the most investment incentive certificates (Ersungur, et al., 2007). More investments and incentives to the regions other rather than North-eastern Anatolia could also be a facilitating factor in accessing the Internet and accessing health care services also tends to be more difficult in underdeveloped regions (Chu et al., 2017).

The unemployed appeared to search for more health information on the Internet than the employed. There can be several reasons for this, and it might be related to the fact that the unemployed have more free time, and, because they tend not to have health insurance, they do not have access to health care services.

When the effect of frequency of Internet use was analysed, it was found that individuals who use the Internet every day and those who use it once a week were more likely to search for health information compared to individuals who use the Internet at least once a month.

The findings of this study indicate that health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet had shown an increasing trend over the years. The sociodemographic factors also explain a significant portion of the variance in this behaviour. According to the results of the logistic regression, the Nagelkerke’s R² explanatory coefficient for 2013 is 0.20, 0.22 for 2015, 0.18 for 2017, and 0.24 for 2019. The explanatory coefficient increased in all years except for 2017.

Patients’ search for health information on the Internet is seen as a remarkable sign of patient participation in health care services and a purposeful and targeted action rather than accepting passive information. Studies about seeking health information on the Internet are therefore of broad interest (Graffigna, et al., 2017). Patients’ search for information about their health and participation in their treatment might provide significant data to professionals. It can, however, also cause negative behaviour such as self-diagnosis and self-medication. At this point, it is crucial for health professionals to share qualified information on the Internet, for the users to be careful about accessing wrong information and disinformation, and for patients to consult with health professionals as well as searching for information online.

Information on the Internet is provided by many sources with variable levels of quality, so it can be difficult to distinguish between accurate and inaccurate information. Some researchers have examined websites presenting health information and found that there were many that present inaccurate information (Ahmadinia and Eriksson-Backa, 2020; Ayantunde, et al., 2007; Gilliam, et al., 2003). Websites presenting vital health care information should be reviewed and monitored by governments or other agencies to ensure their accuracy, completeness, and consistency. It is also important to provide training to individuals about how to obtain appropriate and trustworthy health information on the Internet. Such training could be delivered by governmental units or non-governmental organizations. Websites presenting health information should also be designed so they are easy to use, and the desired information can be reached quickly and easily, without being scarce or dull. If the websites presenting health information present scarce or dull information or are difficult to navigate, the population may end up seeking downright harmful opinions in particular echo chambers.

Some suggestions can be given based on the results of this study. It is a known fact that, although elderly individuals engage in health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet, they face various obstacles, including low trust in the information obtained, difficulty financing the technological hardware, low health literacy, and being alienated from the developing Internet technology (Waterworth and Honey, 2018). It is recommended that services that will improve health and technology literacy in this population be provided to facilitate the access to health information in this group. This would lead to positive results for elderly individuals searching for information on the Internet related to their health.

The analysis shows that low-income individuals are less likely to search for health information on the Internet. Internet access opportunities should thus be increased, and cheap Internet access should be provided by the state. Health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet appears to increase as the education level increases, so it is necessary to encourage the spread of education to the maximum extent possible given public resources, which is an important indicator not only of Internet access but also human development. Technology and Internet literacy should also be included in the curriculum to encourage better online citizenship, which will be necessary in the future, and to clarify the use of this tool in accessing health information. There may also be problems in accessing the Internet in underdeveloped regions, so investment incentives should be increased for such regions and the technological infrastructure should be improved.

Limitations

Of the variables assessed that might have an impact on individuals’ health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet, only socio-economic determinants (i.e., sex, age, education level, residential region, employment status, Internet use frequency, and monthly household income) were included in this study. This is an important limitation of this study. Health information seeking behaviour on the Internet is a very complex, cultural and societal phenomenon and depends on societal cultural norms. It is constrained by infrastructure, available systems and services, and legislation and regulation of use. However, this study was only able to consider the socio-economic dimensions affecting this behaviour because the data set used in this study only included data on these socio-economic characteristics. This is a limitation of the study. Future studies should consider all aspects of that may affect health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet.

Another limitation of the current study is that although the change in the target behaviour based on the survey years was intended to be evaluated since 2004, there was no similarity in terms of content and scope in the Survey on the Usage of Information Technologies in Households up to 2013, so only the data sets for 2013, 2015, 2017, and 2019 were included in the study.

In the current study, we used the answers from participants taking part in the TUIK survey, and the question regarding health information-seeking behaviour on the Internet was a yes or no question. This question did not reveal any information about the kinds of Internet devices and websites that the participants used for this behaviour, which is another limitation of the current study.

About the authors

Dr Murat Konca is working as a research assistant at the Department of Health Care Management, Karatekin University, Cankiri, Turkey. Interests cover health economics, research methods in health care services, statistical analysis, and health care management. He can be contacted at konca71@gmail.com.

Şenol Demirci is working as a research assistant at the Department of Health Care Management, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey. Interests cover health economics, data mining, statistical analysis and health care management. He can be contacted at senoldemrci@gmail.com.

Cuma Çakmak is working as a research assistant at the Department of Health Care Management, Dicle University, Diyarbakir, Turkey. Interests cover health economics, data mining, statistical analysis and health care management. He can be contacted at cuma.cakmak@dicle.edu.tr.

Professor Özgür Uğurluoğlu is working as a professor at the Department of Health Care Management, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey. Interests cover health care marketing and strategic management in health care. He can be contacted at ozgurugurluoglu@gmail.com.

References

Note: A link from the title, or from (Internet Archive) is to an open access document. A link from the DOI is to the publisher's page for the document.

- Ahmadinia, H., & Eriksson-Backa, K. (2020). E-health services and devices: availability, merits, and barriers-with some examples from Finland. Finnish Journal of eHealth and eWelfare, 12(1), 10–21. https://doi.org/10.23996/fjhw.64157.

- Alkhatlan, H. M., Rahman, K. F., & Aljazzaf, B. H. (2018). Factors affecting seeking health-related information through the Internet among patients in Kuwait. Alexandria Journal of Medicine, 54(4), 331-336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajme.2017.05.008.

- Andreassen, H. K., Bujnowska-Fedak, M. M., Chronaki, C. E., Dumitru, R. C., Pudule, I., Santana, S., Voss, H. & Wynn, R. (2007). European citizens' use of E-health services: a study of seven countries. BMC Public Health, 7(1), 53-60. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-7-53.

- Ayantunde, A. A., Welch, N. T., & Parsons, S. L. (2007). A survey of patient satisfaction and use of the Internet for health information. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 61(3), 458–462. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01094.x.

- Beaudoin, C. E., & Hong, T. (2011). Health information seeking, diet and physical activity: an empirical assessment by medium and critical demographics. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 80(8), 586-595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.04.003.

- Boccolini, C. S., & de Souza Junior, P. R. B. (2016). Inequities in healthcare utilization: results of the Brazilian National Health Survey, 2013. International Journal for Equity in Health, 15(1), 150. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0444-3.

- Campbell, R. J., & Nolfi, D. A. (2005). Teaching elderly adults to use the Internet to access health care information: before-after study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 7(2), e19. https://doi.org/e19.10.2196/jmir.7.2.e19.

- Chen, J., & Zhu, S. (2016). Online information searches and help seeking for mental health problems in urban China. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(4), 535-545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-015-0657-6.

- Chu, J. T., Wang, M. P., Shen, C., Viswanath, K., Lam, T. H., & Chan, S. S. C. (2017). How, when and why people seek health information online: qualitative study in Hong Kong. Interactive Journal of Medical Research, 6(2), e24. https://doi.org/10.2196/ijmr.7000.

- Chung, J. E. (2013). Patient–provider discussion of online health information: results from the 2007 Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). Journal of Health Communication, 18(6), 627-648. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2012.743628.

- Cotten, S. R., & Gupta, S. S. (2004). Characteristics of online and offline health information seekers and factors that discriminate between them. Social Science & Medicine, 59(9), 1795-1806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.02.020.

- Din, H. N., McDaniels-Davidson, C., Nodora, J., & Madanat, H. (2019). Profiles of a health information–seeking population and the current digital divide: cross-sectional analysis of the 2015-2016 California Health Interview Survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(5), e11931. https://doi.org/10.2196/11931.

- Ersungur, Ş. M., Kızıltan, A., & Polat, Ö. (2007). Türkiye’de Bölgelerin Sosyo-Ekonomik Gelişmişlik Sıralaması: Temel Bileşenler Analizi [Ranking for socio-economic development of regions in Turkey: principal component analysis]. Atatürk Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Dergisi, 21(2), 55-66.

- Ferguson, T. (2000). Online patient-helpers and physicians working together: a new partnership for high quality health care. British Medical Journal, 321(7269), 1129-1132. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.321.7269.1129.

- Finney-Rutten, L. J., Blake, K. D., Greenberg-Worisek, A. J., Allen, S. V., Moser, R. P., & Hesse, B. W. (2019). Online health information seeking among us adults: measuring progress toward a healthy people 2020 objective. Public Health Reports, 134(6), 617-625. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354919874074.

- Folayan, O. F., Adeosun, F. O., Adeosun, O. T., & Adedeji, B. O. (2017). The influence of the Internet on health seeking behaviour of nursing mothers in Ekiti State, Nigeria. International Journal of Advanced Research and Publications, 1(5), 1-6. https://bit.ly/3NDZHqL. (Internet Archive)

- Gallagher, S., Doherty, D. T., Moran, R., & Katralova-O'Doherty, K. (2008). Internet use and seeking health information online in Ireland: demographic characteristics and mental health characteristics of users and non-users. https://www.lenus.ie/bitstream/handle/10147/336103/HRBResearchSeries4.pdf?sequence=1 (Internet Archive)

- Gencer, Z. T., Daşlı, Y., & Biçer, E. B. (2019). Sağlık iletişiminde yeni yaklaşımlar: dijital medya kullanımı [New approaches in health communication: using digital media]. Selçuk Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Meslek Yüksekokulu Dergisi, 22(1), 42-52. https://doi.org/10.29249/selcuksbmyd.466855.

- Gilliam, A. D., Speake, W. J., Scholefield, J. H., & Beckingham, I. J. (2003). Finding the best from the rest: evaluation of the quality of patient information on the Internet. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, 85(1), 44-46. https://doi.org/10.1308/003588403321001435.

- Glynn, L. G., Valderas, J. M., Healy, P., Burke, E., Newell, J., Gillespie, P., & Murphy, A. W. (2011). The prevalence of multimorbidity in primary care and its effect on health care utilization and cost. Family Practice, 28(5), 516-523. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmr013.

- Graffigna, G., Barello, S., Bonanomi, A., & Riva, G. (2017). Factors affecting patients’ online health information-seeking behaviours: the role of the Patient Health Engagement (PHE) Model. Patient education and counseling, 100(10), 1918-1927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.05.033.

- Gutierrez, N., Kindratt, T. B., Pagels, P., Foster, B., & Gimpel, N. E. (2014). Health literacy, health information seeking behaviors and Internet use among patients attending a private and public clinic in the same geographic area. Journal of Community Health, 39(1), 83-89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-013-9742-5.

- Güzel, A., & Kurtuldu, A. (2018). A study about the Internet use of vocational high school students for health issues. Turkish Studies Social Sciences, 13(18), 741-755. https://doi.org/10.7827/TurkishStudies.13983.

- Haluza, D., Naszay, M., Stockinger, A., & Jungwirth, D. (2017). Digital natives versus digital immigrants: influence of online health information seeking on the doctor–patient relationship. Health Communication, 32(11), 1342-1349. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2016.1220044.

- Hesse, B. W., Nelson, D. E., Kreps, G. L., Croyle, R. T., Arora, N. K., Rimer, B. K., & Viswanath, K. (2005). Trust and sources of health information: the impact of the Internet and its implications for health care providers: findings from the first Health Information National Trends Survey. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165(22), 2618-2624. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.165.22.2618.

- Higgins, O., Sixsmith, J., Barry, M. M., & Domegan, C. (2011). A literature review on health information-seeking behaviour on the web: a health consumer and health professional perspective. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. https://bit.ly/3yXo5zI. (Internet Archive)

- Jacobs, W., Amuta, A. O., & Jeon, K. C. (2017). Health information seeking in the digital age: an analysis of health information seeking behavior among US adults. Cogent Social Sciences, 3(1), 1302785. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2017.1302785.

- Jamal, A., Khan, S. A., AlHumud, A., Al-Duhyyim, A., Alrashed, M., Shabr, F. B., Alteraif, A., Almuziri, A., Househ, M. & Qureshi, R. (2015). Association of online health information–seeking behavior and self-care activities among type 2 diabetic patients in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(8), e196. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4312.

- Jiang, S., & Liu, P. L. (2020). Digital divide and Internet health information seeking among cancer survivors: a trend analysis from 2011 to 2017. Psycho‐Oncology, 29(1), 61-67. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5247.

- Koo, M., Lu, M. C., & Lin, S. C. (2016). Predictors of Internet use for health information among male and female Internet users: findings from the 2009 Taiwan National Health Interview Survey. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 94, 155-163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.07.011.

- Lambert, S. D., & Loiselle, C. G. (2007). Health information-seeking behavior. Qualitative Health Research, 17(8), 1006-1019. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732307305199.

- Lee, C. J. (2008). Does the Internet displace health professionals? Journal of Health Communication, 13(5), 450-464. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730802198839.

- Lee, Y. J., Boden-Albala, B., Larson, E., Wilcox, A., & Bakken, S. (2014). Online health information seeking behaviors of Hispanics in New York City: a community-based cross-sectional study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(7), e176. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3499.

- Levine, D. M., Lipsitz, S. R., & Linder, J. A. (2016). Trends in seniors’ use of digital health technology in the United States, 2011-2014. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 316(5), 538-540. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.9124.

- Li, J., Theng, Y. L., & Foo, S. (2016). Predictors of online health information seeking behavior: changes between 2002 and 2012. Health Informatics Journal, 22(4), 804-814. https://doi.org/10.1177/1460458215595851.

- Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. (1995). Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 80-94. https://doi.org/10.2307/2626958.

- Matusitz, J., & Breen, G. M. (2007). Telemedicine: its effects on health communication. Health communication, 21(1), 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410230701283439.

- Mills, A., & Todorova, N. (2016). An integrated perspective on factors influencing online health-information seeking behaviours. In ACIS 2016 Proceedings (paper 83). https://aisel.aisnet.org/acis2016/83/ (Internet Archive)

- Nangsangna, R. D., & Vroom, F. D. C. (2019). Factors influencing online health information seeking behaviour among patients in Kwahu West Municipal, Nkawkaw, Ghana. Online Journal of Public Health İnformatics, 11(2), e13. https://doi.org/10.5210/ojphi.v11i2.10141.

- Percheski, C., & Hargittai, E. (2011). Health information-seeking in the digital age. Journal of American College Health, 59(5), 379-386. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2010.513406.

- Sedrak, M. S., Soto-Perez-De-Celis, E., Nelson, R. A., Liu, J., Waring, M. E., Lane, D. S., Paskett, E.D., & Chlebowski, R. T. (2020). Online health information–seeking among older women with chronic illness: analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(4), e15906. https://doi.org/10.2196/15906.

- Te Poel, F., Baumgartner, S. E., Hartmann, T., & Tanis, M. (2016). The curious case of cyberchondria: a longitudinal study on the reciprocal relationship between health anxiety and online health information seeking. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 43, 32-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.07.009.

- Tennant, B., Stellefson, M., Dodd, V., Chaney, B., Chaney, D., Paige, S., & Alber, J. (2015). eHealth literacy and Web 2.0 health information seeking behaviors among baby boomers and older adults. Journal of Medical Internet research, 17(3), e70. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3992.

- Tonsaker, T., Bartlett, G., & Trpkov, C. (2014). Health information on the Internet: gold mine or minefield? Canadian Family Physician, 60(5), 407-408.

- Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. (2019). TUIK news bulletin. TUİK Publishing. https://bit.ly/3LUT9CM (Internet Archive)

- Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. (2020). TUIK database. TUİK Publishing. https://biruni.tuik.gov.tr/medas/?kn=72&locale=tr (Internet Archive)

- Waring, M. E., McManus, D. D., Amante, D. J., Darling, C. E., & Kiefe, C. I. (2018). Online health information seeking by adults hospitalized for acute coronary syndromes: who looks for information, and who discusses it with healthcare providers? Patient Education and Counseling, 101(11), 1973-1981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.06.016.

- Waterworth, S., & Honey, M. (2018). On-line health seeking activity of older adults: an integrative review of the literature. Geriatric Nursing, 39(3), 310-317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2017.10.016.

- Weaver III, J. B., Mays, D., Lindner, G., Eroğlu, D., Fridinger, F., & Bernhardt, J. M. (2009). Profiling characteristics of Internet medical information users. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 16(5), 714-722. https://doi.org/10.1197/jamia.M3150.

- Wright, R. E. (1995). Logistic regression. In L. G. Grimm & P. R. Yarnold (Eds.). Reading and understanding multivariate statistics (p. 217–244). American Psychological Association.

- Zhao, S. (2009). Parental education and children's online health information seeking: beyond the digital divide debate. Social Science & Medicine, 69(10), 1501-1505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.08.039.