Smallholder farmers’ satisfaction with agricultural information accessed in rural Tanzania

Tumpe Ndimbwa, Kelefa Mwantimwa,, and Faraja Ndumbaro.

Introduction. Rural smallholder farmers’ satisfaction with the agricultural information they access has only attracted insufficient attention from researchers. As such, this study had to explore the farmers’ satisfaction with this type of information in rural Tanzania.

Method. The study employed a descriptive cross-sectional design alongside quantitative and qualitative approaches. In the study, a sample of 341 respondents comprising 318 conveniently selected smallholder farmers and 23 purposively drawn key informants was used.

Analysis. Quantitative data from the questionnaire survey used were analysed using descriptive statistics whereas qualitative data from interviews and focus group discussions were subjected to thematic analysis.

Results. The findings of the study suggest that smallholder farmers’ satisfaction with agricultural information depends on its type, relevance, and timeliness. However, there are various factors that undermine farmers’ satisfaction with the information. These include inadequacy of extension officers, untimely and unreliable information and sources, information access and use related costs, and language problems.

Conclusion. Smallholder farmers’ satisfaction with agricultural information fosters uptake of innovative farming techniques which translates into sustainable agricultural production.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper935

Introduction

Agricultural information plays a crucial role in fostering the agricultural sector’s development (Koutsouris, 2010) through significantly determining the degree of productivity (Ndimbwa et al., 2020; Soyemi and Haliso, 2015). Nzonzo and Mogambi’s (2016) study has underscored information as a major agricultural input that plays a pivotal role in ensuring farmers seize available opportunities so as to improve their produce. As widely reported, proper use of agricultural information enables farmers to adopt and/or adapt to new and improved practices that enhance yields and incomes (Soyemi and Haliso, 2015). Other scholars (e.g., Mwantimwa, 2019; Silayo, 2016; Mtega et al., 2016; Gunasekera and Miranda, 2011; Lwoga et al., 2011) have noted that access to agricultural information can also influence change and engender progress in the agricultural sector by empowering people with the ability to make informed decisions pertaining to value-adding agricultural production. In support of this view, the study by Kaske et al. (2017) suggests that if we are to see substantial development in the agricultural sector, we have to ensure farmers’ access to timely, reliable, and relevant agricultural information. As such, prosperity in the sector significantly depends on smallholder farmers’ ability to access, acquire, and use relatable agricultural information (Ndimbwa et al., 2019).

Moreover, extant literature shows that access to information on crops, production techniques, agricultural equipment, inputs, market, weather forecasts, credit, and loans enhances farmers’ informed decision-making (Mkenda et al., 2017, Aina, 2004). In fact, access to this information, coupled with expert advice on how to maintain crops’ healthy state (Milovanovic, 2014) ensures that the high harvests are kept well hence enhancing the impact of agriculture. Indeed, agricultural information is a powerful empowerment tool as it banishes ignorance while enlightening and strengthening farmers’ resolve (Nicholas-Era, 2017). Understandably, Odini (2014) summarises that information is a basic driver of success in everyday activity, including farming.

Seemingly recognising this, the government of Tanzania has been making numerous concerted efforts to foster smallholder farmers’ access to agricultural information in a bid to improve production. One of the notable efforts made is the formulation of the National Information and Communications Technology Policy in 2013 and its subsequent amendment in 2016 with the aim of transforming the nation’s subsistence agricultural sector into a commercialised one (United Republic of Tanzania, 2016). Another of these efforts in the government’s establishment of community telecentres in Lugoba, Mpwapwa, Ngara, Dakawa, Kilosa, Mtwara, and Kasulu to ensure that smallholder farmers, especially those with minimal access to telecommunication services, access agricultural information (Ndimbwa et al., 2019; Mwantimwa, 2019, Lwoga et al., 2011).

Furthermore, the government provides training to extension officers who are then deployed across the country where they facilitate smallholder farmers’ access to reliable and timely agricultural information to boost their production. To complement government efforts, big mobile companies such as Vodacom, Tigo, and Zantel provide services that allow smallholder farmers to request for and access necessary agricultural information (Ndimbwa et al., 2019; Barakabitze et al., 2015). For example, Tigo mobile service provider uses the programme called Tigo Kilimo to ‘provide different information to farmers on daily weather forecasts, comprehensive details on soil management, pest control methods, and information on livestock care and life-cycles’ (Levi, 2015, p.50).

Despite these substantial interventions and initiatives aimed to improve access to and use of agricultural information among smallholder farmers in Tanzania, the delivery of these resources remains largely poor (Mwantimwa, 2019, 2017). Regarding this, Nyamba (2017) informs that although the importance of agricultural information to smallholder farmers is well documented, most farmers in developing countries such as Tanzania lack access. This is attributed to the fact that only a small proportion of the information generated reaches the farmers (Siyao, 2012; Mwalukasa, 2013; Food and Agriculture Organization, 2017). In support, Msoffe and Ngulube (2016) add that farmers in rural areas have limited access to and underutilise information.

While this state is widely reported, the reasons behind it are unclear because the majority of existing studies (e.g., Mwantimwa, 2020, 2019; Ndimbwa et al., 2019; Mkenda et al., 2017; Nyamba, 2017; Msoffe and Ngulube, 2016; Silayo, 2016; Mtega et al., 2016; Lwoga et al., 2011) have not explored smallholder farmers’ satisfaction with agricultural information. Instead, the studies mainly focused on access to and use of agricultural information in rural settings. In other words, researchers have paid little research attention to rural smallholder farmers’ satisfaction with the agricultural information they access. Against this backdrop, the present study set out to explore Tanzania’s rural smallholder farmers’ satisfaction with the agricultural information they access. The specific objectives of the study were to identify types of agricultural information smallholder farmers access, examine smallholder farmers’ satisfaction with the information they access, and explore factors undermining the farmers’ satisfaction with the information they access.

Literature review

The concept of the smallholder farmer

Scholars from different disciplines have varyingly defined the term ‘smallholder farmer’. Whereas some rely on the size of farm owned by farmers, others associate it with the quantity of produce. Inevitably, there is variety of definitions of the terms smallholder or small-scale farmers. Generally, a smallholder farmer is one operating under a small-scale agriculture model. Such a farmer usually tills a small lot of land, utilises limited food production techniques or technology, and relies on family members for labour (Khalil et al., 2017). Therefore, smallholdings are usually farms supporting a single family with a mixture of cash crop and subsistence farming.

Information needs and information seeking behaviour

Users’ information needs and seeking behaviour are some of the widely studied topics in information science research. The term ‘information need’ is varyingly used to mean knowledge gap, knowledge deficit, information problem, and desire for information, knowledge discontinuity, or anomalous state of knowledge (Ndumbaro, 2016; Wilson, 1981, 2000). An information need arises when an individual senses a problematic situation that internal knowledge and beliefs fail to suggest a path towards solving it (Amah et al., 2021). In general, a relatively large number of studies have specifically focused on the information needs of farmers (Lwoga et al., 2010; Elly and Silayo, 2013; Phiri et al., 2019). These studies have shown that farmers’ information needs are diverse and heterogeneous as a result of the nature of farming activities (Elly and Silayo 2013), demographic factors (e.g., sex, age and level of education), and geographical location of farmers (Amah et al., 2021; Oyeniyi and Olofinsawe, 2015; Fawole, 2008; Munyua and Stilwell, 2010). The needs can also be categorized based on context (situation-specific need, internally or externally prompted), frequency (recurring or new need), predictability (anticipated or unexpected need), importance (degrees of urgency), and complexity (easily resolved or difficult) (Case, 2002; Wilson, 1981; Amah et al., 2021). However, although these determinants are diverse, a study by Elly and Silayo (2013) revealed that types of farming activities are the main factor responsible for variations in Tanzania’s rural smallholder farmers’ information needs.

Nevertheless, a person’s ability to identify information gaps leads to information-seeking and formulation of requests for information (Amah et al., 2021; Case, 2002; Wilson, 1981). According to Wilson (2000), information seeking behaviour is the totality of human conduct in relation to sources and channels of information including both active and passive information-seeking and information-use to answer a specific query. Diekmann, Loibl and Batte (2009) associate information-seeking behaviour with the procedure used to fill a knowledge gap; whereby individuals make information exchanges influenced by time and space to produce desired outcomes. The term is also used to refer to the micro level of behaviour an information searcher employs to interrelate with information systems of all kinds, be it between the seeker and the system or the pure method of creating and following up on a search (Munyua, 2000; Diekmann et al., 2009). A farmer’s aspiration to seek information and the capacity to accumulate social capital and social learning skills usually shape the information-seeking behaviour. In addition, the content needed and the sources of information that have to be consulted help to refine one’s seeking behaviour (Amah et al., 2021).

Types of agricultural information

Studies on agricultural information (e.g., Ndimbwa et al., 2020; Krel et al., 2020; Phiri et al., 2019; Milovanovic, 2014) have identified different types that smallholder farmers need. In general, the reviewed literature shows that the information smallholder farmers need and access prior to, during, and after production is diverse. For example, a study conducted by Milovanovic (2014) revealed that for smallholder farmers to improve agricultural production, they should have information on crops, production techniques, production equipment and agricultural input and market information. The study also showed that other information types of interest such as weather forecasts, credit availability, and expert advice on maintaining crops in a healthy state are needed. Similarly Magesa, Michael and Ko (2014) reported that the availability of various types of agricultural information enables smallholder farmers to decide what to plant, when to do so, where to sell, and how to negotiate for better agro-produce prices.

Overall, literature shows that the types of information smallholder farmers access have much to do with their need to improve production and boost harvests. For instance, before starting planting, smallholder farmers are likely to ask questions regarding what, where, when, and how to produce (Ndimbwa et al., 2019; 2020). Apparently, a large proportion of smallholder farmers access information on crop production and animal husbandry (see Phiri et al., 2019). An exploration by Diemer et al. (2020) of smallholder farmers’ behaviour in relation to information on organic and conventional pest management strategies in Uganda found that smallholder farmers are more receptive to organic pest management information when encountering a new type of pests. In other words, smallholder farmers develop information needs when they encounter problems in their agricultural activities.

According to existing literature, smallholder farmers need different types of information at different stages of their farming activities to enhance productivity (Mbwangu, 2018). On this, Opara (2008) states that before starting production, smallholder farmers usually need information on weather, loans, soil, seeds, farming mechanisms, and farm management. Similarly, other studies (e.g., Mubofu, 2016; Armstrong and Gandhi, 2012) contend that types of agricultural information such as land mechanisation, application of fertilisers and pesticides, and weeding techniques are needed during crop cultivation whereas that related to storage, markets, sales, investments, and repayment of loans is accessed post-harvesting. Regarding market information, Krell et al. (2020) specify that smallholder farmers in central Kenya accessed information to do with the buying and selling of agricultural products.

Apart from that, a study carried out in Lesotho by Mokotjo and Kalusopa (2010) found that smallholder farmers also need access to financial agricultural information. This information enables them to buy agricultural inputs and improve infrastructure in addition to assuring them about produce markets and prices. Similarly Sani et al. (2014) attest to the importance of this type of information in enhancing results in farming activities. Without such information, farmers will be less sure of what to produce and how to locate potential markets for their produce (Sani et al., 2014). Moreover, access to this and other types of information on new farming practices has the potential of expediting farmers’ adoption of new improved agricultural practices. Similarly, Siyao (2012) asserts that agricultural information acquaints people with better farming methods, improved seedlings, and modern pests control measures hence boosting their awareness on different agricultural developments and challenges. This is necessary in making appropriate livelihood actions.

Satisfaction with accessed agricultural information

Smallholder farmers’ success in their agricultural activities determines the level of their satisfaction with the information they have accessed and utilised for the same purpose. According to the literature reviewed, smallholder farmers’ satisfaction with crucial agricultural information is a vital element in enhancing agricultural production. As revealed by some studies (i.e., Kumar, 2011; Siyao, 2012) farmers’ production decisions are significantly influenced by the amount of information available to them. In the same vein, Soyemi and Haliso (2015) assert that in agriculture, satisfaction with information is a key agro-production determinant. This implies that well informed smallholder farmers who are satisfied with the information they have can make informed decisions that will allow them to improve their agricultural production. Likewise, Adio et al. (2016) confirm that dissatisfaction with the agricultural information accessed and used could have serious, or even, perilous consequences for smallholder farmers’ agricultural success. Nicholas-Ere (2017) demonstrates that when smallholder famers are dissatisfied with their access to information needed to help them to maximise their yields, they are left without no more choices than moving to urban centres for employment. As such, the survival and growth of the agricultural sector in developing countries suffer because they both depend on smallholder farmers (Mkenda et al., 2017; Elias et al., 2015).

Empirically, eariler studies on farmers’ satisfaction with agricultural information reveal mixed findings. For instance, an assessment of Nigerian vegetable farmers’ satisfaction with market information received revealed a 34.7% satisfaction rate (Otene et al., 2016). Other studies examining access to agricultural information (e.g., Pervaiz et al., 2020; Raza et al., 2020; Levi, 2015; Elias et al., 2015; Ramli, et al., 2013; Shaffril et al. 2012; Khatoon-Abadi, 2011; Fossard, 2005; Mirani et al., 2003) indicate that farmers derive satisfaction from diverse agricultural information they access. For example, Levi (2015) found that the majority (more than 50%) of the farmers surveyed were satisfied with the agricultural information they accessed through different channels like television, radio, and mobile phones. On the same note, a study by Pervaiz et al. (2020) reveals a 50% satisfaction rate with the agricultural information. Timeliness and relevance of agricultural information were found to be highly associated with farmers’ satisfaction (Raza et al., 2020; Msoffe and Ngulube, 2016; Msoffe, 2015; Siyao, 2012; Fossard, 2005; Mirani et al., 2003).

Accordingly, Ramli et al. (2013), in their study on farmers’ satisfaction with agricultural information received from television programmes, revealed a high level of satisfaction with information on crop farming, livestock husbandry, and good agricultural practices. In contrast, Sharma, Kaur and Gill (2012) reported that farmers were dissatisfied with different agricultural information delivered to them on matters such as weather, market prices, plant protection (e.g., disease and pest control), and seed varieties. Similarly, a study by Omar et al. (2013) reported that some farmers were dissatisfied with the reliability of weather forecasts. Lack of satisfaction stemming from unreliability of agricultural information delivered to farmers was also reported by other researchers (i.e., Omar et al., 2013; Sharma et al., 2012). On their part, Msoffe and Ngulube (2016) report that smallholder farmers that are satisfied with the information they access are more likely to use and benefit from it. As such, when deciding which information to provide farmers with, factors such as reliability and relevance must be considered.

Factors undermining farmers’ satisfaction with information accessed

Existing studies reveal that smallholder farmers’ satisfaction with the information they access is undermined by diverse factors such as shortage of supporting infrastructure, lack of interest, incompatible information formats, and maintenance problems (Brhane, 2017). Besides these, lack of timely and context-specified information, and users’ inadequate knowledge and skills on how and where to access information tend to influence satisfaction with information (Galadima, 2014; Omar et al., 2013). In a study of farmers’ information needs and search behaviour, a study by Babu et al. (2012) found that unreliability and untimeliness of information are some of the major factors that undermine smallholder farmers’ satisfaction with the information they access. In addition, Daudu et al. (2009) noted that financial constraints, inadequacy and unreliable information infrastructure, lack of information professionals to repackage agricultural information, and the presence of irrelevant information are some of the factors that undermine farmers’ satisfaction with agricultural information. Similarly, a meta-analysis of information behaviour of rural smallholder farmers in selected developing countries revealed diverse challenges. For example, Phiri and Chawinga (2019) found that problems such as lack of mobility, finance, rural information centres, and visits by extension officers limit information access and usage in rural settings. In fact, findings from a study by Phiri, Chipeta and Chawinga (2019) identify lack of mobility as a major problem affecting majority (76.6%) of the rural smallholder farmers in Malawi.

On the same theme, a study conducted by Daniel et al. (2013) revealed unsatisfactory smallholder farmers’ access to correct information as a result of poor co-ordination of agricultural extension services. Moreover, Duta (2009) found that farmers’ dissatisfaction with information resulted from lack of access to electric power, inability to afford batteries, and, sometimes, unfavourable timing of agricultural programs aired on various media outlets. On their part, Otene et al. (2016) identified unavailability of desired channels of information and unreliability of information as some of the factors undermining farmers’ chances of being satisfied. Similarly, Sobalaje et al. (2019) observed that unavailability of relevant information and inadequacy of current information were the critical problems extension workers faced in their attempts to ensure farmers are satisfied with agricultural information. In addition, social norms in a social system have been noted to have detrimental effects on the use of information and innovation in organic farming (see Adebayo and Oladele, 2012). According to Msoffe and Ngulube,

most farmers (60%) were not satisfied with information dissemination services. Inadequate information services from extension officers, lack of reliable sources of information, lack of awareness of the availability of information, and unavailability of extension officers were cited as the main reasons for dissatisfaction. (2016, p.177)

Theoretical framework

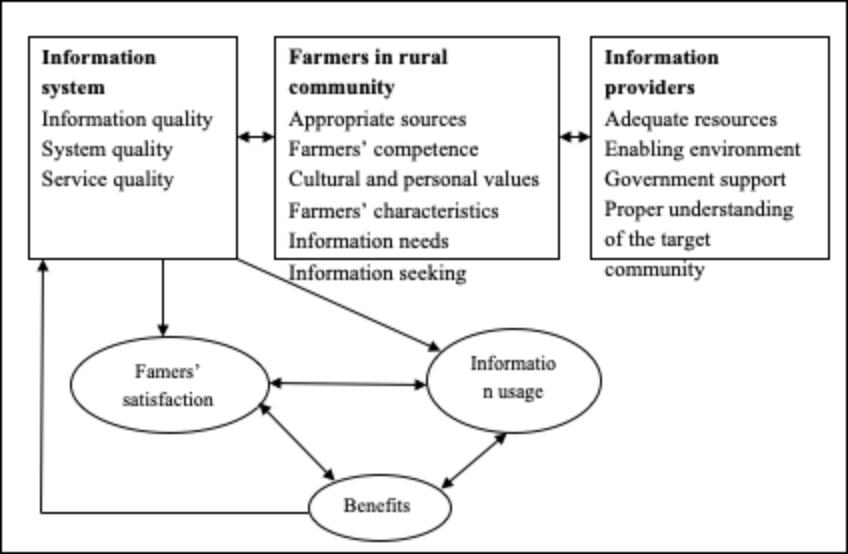

The model for dissemination of agricultural information proposed by Msoffe (2015) was used to guide this study. The model comprises six interrelated components: information system, farmers in rural community, information providers, farmers’ satisfaction, information usage, and benefits. To ensure effective information dissemination, each component requires important elements. These elements are farmers’ information needs; appropriate information sources; farmers’ competences; cultural and personal values; farmers’ characteristics; and information-seeking patterns. According to the model, for information providers to accomplish their work effectively, they require to consider factors such as the availability of adequate resources, the presence of an enabling environment and support from the government, and proper understanding of the target community. The design of an ideal information system needs to have a targeted rural community in mind. The elements to consider when designing an appropriate information system include information quality, system quality, and service quality. These three elements can promote information usage and ensure farmers’ satisfaction. The model’s assumption is that after using agricultural information and reaping associated benefits, farmers are likely to consult the information system again to access more information. However, for this to happen, the information being disseminated must be relevant to the farmers’ needs and be able to help them to improve their farming activities or result in noticeable benefits. Figure 1 presents the model:

Figure 1: Model for disseminating agricultural information. Source: Msoffe and Ngulube (2016)

The main proposition of the model is that farmers’ satisfaction with accessed agricultural information depends on an information system (i.e., information quality, service quality, and system quality), information providers (i.e., enabling factors), and farmers’ capabilities (i.e., ability to identify needs, and seek and use information). The model also suggests that farmers' satisfaction with information is directly dependent on information usage and benefits of doing so. Msoffe (2015), in an investigation of access to and use of poultry management information in rural areas, found that farmers interact with information systems to satisfy their information needs. In other words, a system’s usage depends on farmers’ possession of information needs that have to be met. The model further indicates that smallholder farmers that are satisfied with the information delivered to them are more likely to be the same ones experiencing benefits from it. The relevance of agricultural information and appropriateness of sources from which it comes determine farmers’ satisfaction. Farmers thereby use relevant information to decide on the recommended farming practices to apply benefit by improving their production (Msoffe and Ngulube, 2016). This model was found suitable for this study because it covers variables pertaining to smallholder farmers’ satisfaction with agricultural information delivered to them.

Research methods

Research design and approaches

This study deployed descriptive and cross-sectional research designs to investigate smallholder farmers’ satisfaction with agricultural information in Kyela district, Tanzania. The descriptive design tends to be quantitative and qualitative in nature and can generate more information on phenomena within a particular research problem by describing them (Tavakoli, 2012). In contrast, a cross-sectional design was adopted in this study because data collection was scheduled for one point in time (Tavakoli, 2012; Creswell, 2014). In fact, most studies carried out as part of academic programmes are generally time-constrained hence the need to collect data in one instance (Saunders et al., 2003). Under these designs, both qualitative and quantitative approaches were employed to collect and analyse data. In other words, a mixed research approach suitable “for mixing quantitative and qualitative data at some stage of the research process within a single study in order to understand a research problem in a more complete way” was employed (Tavakoli, 2012, p. 362). The overwhelming advantages of this approach also known as a triangulation approach inexorably made it the preferred one (Mwantimwa, 2012).

Generally, the approach was chosen because of the study’s need to collect in-depth research data on agricultural information accessibility and farmers’ satisfaction with accessed information. Besides this, the approach provides researchers with a variety of data collection, processing, and analysis methods (see also, Antwi-Agyei and Nyantakwi-Frimpong, 2021; Phiri et al., 2019; Reincke et al., 2018). In the approach, the qualitative part was used to explore smallholder farmers’ opinions, perceptions, and views regarding the studied variables while the quantitative part was useful in examining factors undermining smallholder farmers’ satisfaction with agricultural information delivered to them. Through these approaches the study collected quantitative data on socio-demographic characteristics of respondents and types of agricultural information. The combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches helped the researchers to generate evidence on the research problem under investigation. Overall, there is a growing interest in the employment of mixed design and approach in research (see Zhang and Watanabe-Galloway, 2014).

Study settings

This study was conducted in seven villages of Kyela district in Mbeya Region. These were Kisale, Kingili, Kange, Ushirika, Kisyosyo, Matema, and Kasumulu. The choice of these villages was purposively made because the presence of many smallholder farmers (Ngailo et al., 2016). The study targeted smallholder farmers because they are known to cultivate between 85 and 90% of the world’s agricultural land. In fact, these farmers produce is responsible for a third of the gross domestic product and employs about 67-70% of rural households (World Bank, 2019). In Tanzania, these farmers contribute about 70% of agricultural production (Edson and Akyoo, 2021; Msuya et al., 2018). Despite this contribution, these farmers are nowhere near the potential since their productivity remains low.

Previous studies in information science (e.g., Mkenda, 2017; Siyao, 2012) associated the farmers’ low productivity with limited agricultural information; a factor that raises the question of how satisfied these farmers are with the delivery of agricultural information. Although this question needs to be asked for smallholder farmers in majority of districts, this study only focused on those in selected villages in Kyela district because there was insufficient time to study the whole community. Generally, the population of Kyela district is made of smallholder farmers. As such, using seven representative villages was considered practical. More significantly, the choice of the study area was based on its geographical location and types of crops (e.g., rice, cocoa and cashew) grown by smallholder farmers.

Study population, sample and sampling procedures

In this study, the population targeted was made of smallholder farmers aged 20 years or above. This age group was selected because it relies on agriculture as their main economic activity. Key informants (i.e., agricultural extension, gatekeeper farmers, executive officers, researchers, and village leaders) were also part of the study. These key informants were included because they play key roles in the production, delivery, and use of agricultural information. In all, the study involved a sample of 341 respondents. To select the sample, two non-probability sampling procedures (i.e., convenience and purposive) were employed. Specifically, 318 smallholder farmers were conveniently selected while twenty-three key informants were purposively picked.

Having access to all smallholder farmers was quite impossible due to diverse reasons such as financial and time constraints. As a result, convenience sampling was used to draw the required sample. Various studies (e.g., Elfil and Negida, 2017; Onwuegbuzie and Collins, 2017) show that convenience sampling is one of the most applicable methods for picking samples from inaccessible populations. The method is quick, inexpensive, and convenient. According to Tavakoli (2012), the ease of locating elements of a sample, geographical distribution of the sample, and the ease of obtaining data from selected individuals are vital factors informing sampling procedure choices. In all, accessibility, willingness, and proximity to potential participants are the primary considerations made when picking convenience sampling method (Sarstedt et al., 2018; Elfil and Negida, 2017; Onwuegbuzie and Collins, 2017; Baker et al., 2013).

Data collection methods and instruments

This study employed cross-sectional surveys (i.e., questionnaire, interview), focus group discussions and observations to collect data. In other words, multiple data gathering methods were used to collect data. Mtega and Bernard (2013) contend that using multiple data collection methods is particularly useful in exploring people’s knowledge and experiences can help to examine not only what people think but also how they think and why they think that way. In this study, mixed research methods helped to establish trustworthiness of data since triangulation helps to increase the validity and credibility of research.

A content validity method helped to design research instruments used in the study. The researchers prepared first drafts of research instruments based on the study objectives and research questions. Thereafter, research experts reviewed the research instruments and made critical assessments of the quality and relevance of the questions or items in them. These assessments provided valuable inputs that enhanced the tools’ content validity. The experts did not only examine the appropriateness of the items and their wording, but also assessed the structure of the instruments and their potential hence providing a holistic view of the instruments quality (Qasim et al., 2018, 2019). All the comments raised by the experts were incorporated in the subsequent drafts of the instruments. After being reviewed, the instruments were edited and pre-tested to improve their reliability and validity. The pre-tests were carried out in Rungwe district. During this exercise, unclear words were omitted or adjusted accordingly to enhance clarity and the validity of the instruments. During this stage, the researchers adjusted the instruments to the population’s textual understanding level. After this, the drafts were revised, edited, and before being produced for fieldwork. This involved translation of the instruments into the Swahili language to enhance respondents’ understanding and the reliability of data.

In all, 318 questionnaires with both closed and open-ended questions were administered by the researchers and research assistants to smallholder farmers. This approach was used because of literacy challenges among the respondents. Choudhury (n.d.) supports that one of the major limitations of using questionnaires is their ineffectiveness when respondents do not have enough education. Questionnaires cannot be used by illiterate and semi-literate persons. The process lasted 30-45 minutes per questionnaire. Scales such as nominal and ordinal (Likert scale) were used in the questionnaires. To measure the level of satisfaction, a Likert scale (1 = Very satisfied, 2 = Satisfied, 3 = Nether neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, 4 = Very dissatisfied and 5 = Dissatisfied) was used. The verbal responses to questions were recorded by the researchers and research assistants in the questionnaires. Not all the questions in the questionnaires yielded detailed information that provided a deeper understanding of smallholder farmers’ satisfaction with information. Questions meant to obtain detailed information were, therefore, asked during interviews and focus group sessions. These methods provided researchers with opportunities to capture detailed information that was not possible through questionnaires.

Accordingly, semi-structured face-to-face interviews and focus group discussions were carried out by the researchers with key informants. The interview used a semi-structured guide in face-to-face interview sessions that lasted 20-30 minutes. The researchers used a notebook and a tape-recorder to record responses. Apart from that, three focus group discussion sessions were held with smallholder farmers and key informants. Each session had a group of eight to ten participants. This number of participants was appropriate as recommended by Kumar (2011, p.124) who asserts that it is optimal for such discussion groups. There were no difficulties to ensure gender diversity in the focus groups since the culture of the communities surveyed encourages interaction between males and females. During the focus group discussions, every participant had an opportunity to provide their opinions, views, and perceptions on the agricultural information they had access to. After the discussions, a consensus was reached, and opinions highly agreed upon were recorded by the researchers. In addition, the researchers observed issues related to channels used to deliver information to smallholder farmers in the study area. An observation checklist with different variables facilitated data collection on sources and channels used to deliver agricultural information. To collect secondary data, this study used a variety of sources, such as Statistics about agriculture in Tanzania, (Statista, 2021), Tanzania agriculture: Tanzania agriculture value and growth 2014-2018, (TanzaniaInvest, 2019, the agricultural statistics of the Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics (2019), and the national information and communications technology policy (United Republic of Tanzania, 2016)

Ethical issues

In this study, ethical considerations and procedures established by the University of Dar es Salaam were followed. Before going for data collection in the field, a research clearance letter and permit were obtained from the Directorate of Research and Publications of the University of Dar es Salaam. The clearance letter helped the researchers to obtain permission from authorities in the selected study areas. The researchers obtained permission from responsible government offices including Mbeya Regional Administrative Secretary, Dodoma Regional Administrative Secretary, and the Kyela District Administrative Secretary. Introduction letters from these authorities enabled the researchers to visit and collect data in the selected study areas. Before data collection, the research team carried out sensitisation sessions for ward and village leaders to introduce them to the research project and assistants. Besides, assurances of confidentiality were made at the beginning of data collection. The researchers introduced themselves, the purpose of the study, and made clear the purpose for which the data was going to be used. Paramount in these assurances were issues of anonymity and confidentiality to cultivate trust among respondents.

Data processing and analysis

The completion of data collection was followed by analysis. Under this stage, qualitative and quantitative data were analysed separately. Whereas the quantitative approach was used to process and analyse data collected from questionnaires, the qualitative approach was used to analyse data that emanated from interviews and focus group discussions. Prior to analysis, quantitative data were organised, verified, compiled, coded, and analysed by using the 21st version of IBM's SPSS Statistics. Processing quantitative data involved editing, coding, creating a data set, data entry into SPSS, data cleaning and producing descriptive statistics, and data presentation in tables. Descriptive statistics were used to generate frequencies and percentages of the investigated variables as well as to organize and summarise data. On the other hand, qualitative data from open questions in questionnaires, focus group discussions, and interviews were analysed using a thematic method. This was done through transcription, familiarisation of data, identification of codes, constructing themes, revisiting themes, defining themes, and presenting data in narration form. Accordingly, reorganisations of different sub-themes, as well as identification of similar and dissimilar aspects of data were careful done manually. Finally, quantitative and qualitative results were reported concomitantly through using qualitative results to elaborate on and validate quantitative ones.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents

Respondents were asked to indicate their socio-demographic characteristics. Specifically, the characteristics of interest were sex, age, marital status, and education level as Table 1 illustrates:

| Characteristics (n = 318) | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 213 | 67.0 |

| Female | 105 | 33.0 |

| Age | ||

| Below 21 | 4 | 1.3 |

| 21-30 | 62 | 19.5 |

| 31-40 | 89 | 28.0 |

| 41-50 | 92 | 28.9 |

| Over 50 | 71 | 22.3 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 271 | 85.2 |

| Single | 14 | 4.4 |

| Divorced | 7 | 2.2 |

| Widowed | 18 | 5.7 |

| Separated | 8 | 2.5 |

The study results indicate that most (67%) of the smallholder farmers that participated in this study were males. The findings further signify that more than three-quarters (76.4%) of the respondents were in the 21-50 years age-group, followed by 22.3% that were aged over 50 years. Meanwhile, only 1.2% of the respondents were made of individuals aged below 21 years. In other words, a significant proportion of smallholder farmers comprised young adults and middle-aged people who were likely to actively engage in agricultural production. This is a good thing because the surveyed communities’ livelihoods are hugely dependent on agricultural production. Furthermore, the results indicate that most (85.2%) respondents were married while only a few were single, divorced, separated, or widowed. In other words, the smallholder farmers in the area live with their partners.

Status of agricultural information accessibility

To understand the status of accessibility of different types of agricultural information delivered to smallholder farmers in the villages surveyed, the farmers were asked about the status of various types of information delivered to them through various sources and channels. A five Likert scale (Excellent, Very Good, Good, Fair and Poor) was used to gauge the status of agricultural information accessibility. Their responses are presented in Table 2:

| Information type | Excellent | Very good | Good | Fair | Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market information | 9(2.8%) | 24 (7.5%) | 37(11.6%) | 68(21.4%) | 180(56.6%) |

| Climate variation | 6(1.9%) | 39(12.3%) | 154(48.4%) | 70(22.0%) | 49(15.4%) |

| Credit and loan | 9(2.8%) | 30(9.4%) | 45(14.2%) | 89(28.0%) | 145(45.6%) |

| Afforestation | 8(2.5%) | 45(14.2%) | 176(55.3%) | 60(18.9%) | 29(9.1%) |

| Weather | 7(2.2%) | 69(21.7%) | 186(58.5%) | 38(11.9%) | 18(5.7%) |

| Improved seeds | 5(1.6%) | 94(29.6%) | 183(57.5%) | 26(8.2%) | 10(3.1%) |

| Production techniques | 3(0.9%) | 56(17.6%) | 210(66.0%) | 38(11.9%) | 11(3.5%) |

| Pesticides | 2(0.6%) | 42(13.2%) | 186(58.5%) | 69 (21.7%) | 19(6.0%) |

| Legal information | 0(0.0%) | 6(1.9%) | 21(6.6%) | 79(24.8%) | 212(66.6%) |

| Incentives | 2(0.6%) | 8(2.5%) | 37(11.6%) | 60(18.9%) | 211(66.4%) |

| Post-harvest | 3(0.9%) | 24(7.5%) | 157(49.4%) | 90(28.3%) | 44(13.8%) |

| Animal husbandry | 4(1.3%) | 13(4.1%) | 186(58.5%) | 78(24.5%) | 37(11.6%) |

| Transport | 4(1.3%) | 8(2.5%) | 62(19.5%) | 118(37.1%) | 126(39.6%) |

| Animal feed | 3(0.9%) | 13(4.1%) | 100(31.4%) | 104(32.7%) | 98(30.8%) |

| Vaccination | 4(1.3%) | 50(15.7%) | 208(65.4%) | 33(10.4%) | 23(7.2%) |

| Livestock breeding | 3(0.9%) | 8(2.5%) | 47(14.8%) | 126(39.6%) | 134(42.1%) |

Overall, the results presented in Table 2 indicated varying statuses of the accessibility of different types of agricultural information to smallholder farmers in the wards surveyed in Kyela. The overall results indicate that most (66.1%) smallholder farmers in the district reported the accessibility of information on production techniques as good, followed by that on animal vaccination (65.2%), weather (58.6%), and pesticides (58.3%). The results further reveal that 57.4% of the smallholder farmers said they received information on improved seeds, followed by 49.5% that indicated that they received post- harvest information, and 48.3% that reported to receive information on climate variations as well as credit and loans.

On the other hand, the results indicate that more than half (66.1%) of the smallholder farmers reported that the accessibility of legal information was poor, followed by that on marketing (56.4%), livestock breeds (42%) and transportation (39.7%). These results imply that in the surveyed study area, some types of agricultural information were accessible to smallholder farmers while the accessibility of others was poor or fair as Table 2 illustrates. The results are similar to those obtained from face-to-face interviews and focus group sessions. Key informants reported that smallholder farmers were delivered with diverse agricultural information. The results also show that the farmers in the study area needed other types of agricultural information such as that on agricultural inputs, land preparation, climate changes, when to sow seeds, types of seeds, application of fertiliser and pesticide, and market prices of cash crops such as cocoa, rice and cashew nuts. The findings further show that smallholder farmers needed agricultural information related to how to plant in lines, weeding, harvesting, and how to store crops after harvests. In support of results from the main survey, interviews, focus groups, and observations, one of the extension officers interviewed said:

We always receive various types of agricultural information from TARI-Uyole Agricultural Institute and the Ministry of Agriculture…we receive information on new improved seeds, types of fertilisers TSP, SA, UREA, Minjingu, Dap and their application…also knowledge related to planting in lines, usage of power tillers in both uplands and in irrigation schemes, how to prepare farms, and the use of plough in cultivation…we deliver the information to farmers in our areas (Male, extension officer, aged 32).

Similarly, one of the smallholder farmers from Matema ward said the following during focus group discussions:

we access different types of information related to agricultural production from agricultural officers. The information provided to us is important as we see progress in our production. However, some of our fellow smallholder farmers, particularly those who are not in groups ignore or fail to effectively utilize the information due to their own reasons (Female, smallholder farmer, aged 35).

Along the same line, one extension officer explained that:

One of our roles as extension officers is to provide agricultural information to farmers, especially on fertilisers to use, how to preserve fertilisers, and the use of different pesticides. We also inform them about current market prices (Male, extension officer, aged 39).

This indicates that smallholder farmers have access to information on diverse areas including farm preparation, sowing, weeding, fertilisation, pesticides, harvesting and post harvesting. However, the accessibility of these information types varies.

Satisfaction with agricultural information farmers’ access

The question on satisfaction with accessed agricultural information was central in this study because it was expected to provide more insights on the topic. As such, smallholder farmers were asked to indicate their levels of satisfaction with the agricultural information delivered to them. An ordinal scale (i.e. 1: very satisfied, 2: satisfied, 3: neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, 4: dissatisfied and 5: very dissatisfied) was used to rate levels of satisfaction. In general, results indicate that close to three-fifths (58.5%) of smallholder farmers in the wards surveyed were satisfied with the agricultural information they accessed whereas just over a quarter (26.7%) were dissatisfied and 9.4% did not respond. Accordingly, the respondents were asked to indicate their level of satisfaction with various types of agricultural information. The results obtained are as presented in Table 3:

| Information type | Very satisfied | Satisfied | Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | Dissatisfied | Very dissatisfied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market information | 10 (3.1%) | 26 (8.2%) | 94 (29.6%) | 183 (57.5%) | 5 (1.6%) |

| Climate variation | 4 (1.3%) | 23 (7.2%) | 50 (15.7%) | 208 (65.4%) | 33 (10.4%) |

| Credit and loan | 2 (1.9%) | 42 (13.2%) | 186 (58.5%) | 69 (21.7%) | 19 (6.0%) |

| Afforestation | 12 (3.8%) | 4 (1.3%) | 104 (32.7%) | 98 (30.8%) | 100 (31.4%) |

| Weather | 48 (15.1%) | 126 (39.6%) | 7 (2.2%) | 134 (42.1%) | 3 (0.9%) |

| Improved seeds | 45 (14.2%) | 60 (18.9%) | 176 (55.3%) | 29 (9.1%) | 8 (2.5%) |

| Production techniques | 45 (14.2%) | 146 (45.9%) | 89 (28.0%) | 30 (9.4%) | 8 (2.5%) |

| Pesticides | 6 (1.9%) | 39 (12.3%) | 154 (48.4%) | 70 (22.0%) | 49 (15.4%) |

| Legal information | 9 (2.8) | 37 (11.6) | 24 (7.5%) | 180 (56.6%) | 68 (21.4%) |

| Incentives | 2 (0.6%) | 8 (2.5%) | 37 (11.6%) | 60 (18.9%) | 211 (66.4%) |

| Post-harvest | 3 (0.9%) | 8 (2.5%) | 62 (19.5%) | 118 (37.1%) | 127 (39.9%) |

| Animal husbandry | 37 (11.6%) | 78 (24.5%) | 13 (4.1%) | 187 (58.8%) | 3 (0.9%) |

| Transportation | 98 (30.8%) | 48 (15.1%) | 100 (31.4%) | 104 (32.7%) | 4 (1.3%) |

| Animal feed | 37 (11.6%) | 69 (21.7%) | 187 (58.8%) | 18 (5.7%) | 7 (2.2%) |

| Vaccination | 90 (28.3%) | 158 (49.7%) | 43 (13.5%) | 24 (7.5%) | 3 (0.9%) |

| Livestock breeding | 38 (11.9%) | 56 (17.6%) | 211 (66.4%) | 10 (3.1%) | 3 (0.9%) |

The results in Table 3 indicate that most (more than 50%) of the responding smallholder farmers were satisfied with agricultural information related to vaccination, weather, and production techniques. These were followed by information on transportation of agricultural inputs and outputs, animal husbandry, improved seeds, animal feeds, and livestock breeds. On the other hand, the smallholder farmers were not satisfied with information on post-harvests, incentives, legal matters, pesticides, credit and loans, markets, afforestation, and climate variations. To establish why smallholder farmers were satisfied with the agricultural information they accessed, the study required them to provide reasons for their satisfaction levels. The responses provided on this are presented in Table 4:

| Satisfaction level | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Information accessed improves practical farming | 59 | 29.5 |

| Provides opportunities to gain new knowledge | 57 | 28.5 |

| Increases awareness on agricultural production techniques | 49 | 24.5 |

| Information provided is adequate to make farming decisions | 12 | 6.0 |

| Some of the accessed information is relevant to our needs | 12 | 6.0 |

| Sometimes timely information is provided | 11 | 5.5 |

As Table 4 indicates, smallholder farmers in the wards surveyed were satisfied with the agricultural information delivered because it enabled them to improve their farming (29.5%); provided them with new knowledge (28.5%), and raised their awareness on farming practices (24.5%). Others mentioned timely and relevant agricultural information as reasons behind their satisfaction. These results concur with those stemming from interviews and focus groups, which confirmed that information accessed enabled smallholder farmers to gain new practical knowledge and farming skills and techniques. One of the smallholder farmers from Matema village commented:

Although we have inadequate extension officers in our area, the use of demonstration plots and training of trainers is important in sharing agricultural information. Through demonstration plots, farmers are informed on improved seeds and farming techniques. …farmers can test new seeds in demonstration plots and decide either to use them or not. This information is very helpful (Male, smallholder farmer, aged 56).

In other words, smallholder farmers are satisfied with the information delivered due to the effectiveness of some of the mechanisms applied to disseminate it. These, in one way or the other compensate for the inadequacy of information delivered by extension officers.

Factors undermining farmers’ satisfaction with information accessed

Though the findings presented in Table 4, it can be seen that farmers were satisfied with the information delivered to them because of various positive factors. The results also show that 37.1% of smallholder farmers revealed reasons for their dissatisfaction. Although they were supplied with agricultural information, farmers in groups said they were not satisfied with it, especially that on pesticides, weather, and markets. To establish the reasons undermining their satisfaction with the agricultural information delivered, the respondents were asked to indicate the factors behind their dissatisfaction. The results are as summarised in Table 5:

| Low level of satisfaction | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient information | 43 | 36.4 |

| Untimely information | 38 | 32.2 |

| Inadequate extension officers | 16 | 13.6 |

| High costs | 9 | 7.6 |

| Lack of electricity | 8 | 6.8 |

| Language used | 4 | 3.4 |

Generally, the study findings show that over a third (36.4%) of smallholder farmers were not satisfied with the information delivered to them because it was too insufficient. Another 32.2% of the respondents indicated that the agricultural information delivered was untimely. Impliedly, although agricultural information was delivered to the smallholder farmers, it was too inadequate and untimely. These results concur with those from the focus groups. In this regard one of the focus group participants said:

last year (2018) during a village meeting, our extension officer instructed farmers to plant a new improved rice seed known as Sallo 5 that produces more yields. However, we had already planted our own traditional seeds by then (Male, farmer, aged 42).

Another smallholder farmer disclosed that:

The other time they told us to grow crops that take shorter periods to mature and ripen due to weather problems. But we had already planted crops that take a long time to mature (Male, farmer, aged 55).

Similar results were obtained during an interview sessions during which one interviewee said:

extension officers provide the same information every year without updates. But if you use other sources you can access current information compared to what you were told (Male, farmer, aged 51).

In the same context, another smallholder farmer, while explaining reasons for low satisfaction with the agricultural information delivered in the study area, commented:

There is a shortage of extension officers in rural areas... also even those few available are not sometimes well informed in their areas of specialisations. As a result, they give us wrong and, sometimes, out-dated information (Male, teacher and farmer, aged 48).

These statements indicate that smallholder farmers were aware and ready to use the information available in their farming activities. However, most of them were dissatisfied with how the information was provided. On this, one group member of cocoa growers reported that:

the knowledge we have on pesticides is inadequate. As you can see, trees are affected by diseases. We were taught to use a traditional pesticide but it is not working. Also, we are not sure of where we can get good prices for our yields. As a result, we sell our produces at low prices (Male, farmer, aged 36).

Although farmers were reportedly satisfied with the agricultural information delivered to them, some indicated that the information was insufficient, thus failing to meet all their needs. Regarding the shortage or lack of extension officers with up-to-date information, another respondent said:

it is not enough for every village to have its own agricultural extension officer if the officer is not instrumental in assisting farmers to access and use relevant information to improve the quality of their agricultural produce (Female, smallholder farmer, aged 42).

Apparently, smallholder farmers’ satisfaction with the agricultural information they access generally depends on the qualification of extension officers. Qualified extension officers can provide farmers with up-to-date agricultural information. In this regard, short courses and seminars would do a great job in updating the knowledge and skills of extension officers.

Discussion

This study has examined smallholder farmers’ satisfaction with the delivery of agricultural information in rural Tanzania. Generally, the findings suggest that a variety of agricultural information is delivered to these farmers. Specifically, farmers have access to agricultural information on animal husbandry and breeding, vaccination, crop production techniques, post-harvest activities, as well as pesticides and herbicides. These findings are in line with those reported by Milovanovic (2014) who noted that smallholder farmers accessed information on crops, production techniques, production equipment, and agricultural inputs and market information and other topics of interest such as weather forecasts, credit, and expert advice on maintaining crops in a healthy state. Magesa, Michael and Ko (2014) add that the availability of various types of agricultural information enables smallholder farmers to decide on what to plant, when to do so, where to sell, and how to negotiate good produce prices. These findings also support earlier studies that reported that improvement of agricultural production depends on the availability of timely agricultural information (i.e., Ndimbwa et al., 2020; Mbwangu, 2018).

Regarding smallholders’ satisfaction with the agricultural information delivered to them, the findings have revealed that not all the agricultural information accessed by the farmers satisfy them. A higher satisfaction level was mainly recorded on information related to weather, production techniques, transportation, and animal vaccination while low satisfaction was seen in information related to markets, and post-harvest matters. In addition to these, the farmers were not satisfied with information on climate variations, afforestation, pesticides, legal issues, incentives, and credit and loans. Similarly, previous studies (e.g., Ramli et al., 2013) revealed higher level of satisfaction with information on crop farming, livestock husbandry, and good agricultural practices. The findings have shown that the information’s ability to increase awareness on new farming techniques, facilitate acquisition of new agricultural knowledge, improve farming decisions making ability, and its relevance and timeliness are the main factors behind smallholder farmers’ satisfaction. Apart from the reported satisfaction, the findings have also clearly shown that some of information accessed does not satisfy the some smallholder farmers’ needs.

The model for dissemination of agricultural information by Msoffe (2015) affirms that appropriateness and relevance of information and sources determine farmers’ satisfaction because they foster information use. This corroborates findings by Msoffe and Ngulube (2016). Similarly, the findings of this study suggest that relevant and timely information on new farming practices can expedite farmers’ adoption of new and improved practices capable of leading to their satisfaction. These findings tally those from other studies (e.g., Raza et al., 2020; Ramli et al., 2013; Siyao, 2012; Fossard, 2005). However, the findings are contrary to what was found by Sharma, Kaur and Gill (2012) who recorded that the farmers expressed dissatisfaction with different agricultural information delivered to them on subjects such as weather, market prices, plant protection (e.g., disease and pest control), and seed varieties. The findings further reveal that smallholder farmers can collectively be satisfied as they receive and access timely agricultural information from non-governmental organisations, buyers, input suppliers, and financial institutions. These parties use farmers’ groups to reach significant numbers of smallholder farmers.

Factors such as inadequacy of extension officers, insufficient and untimely information, language barriers, and access costs undermine smallholder farmers’ level of satisfaction with the agricultural information accessed. In fact, in recent years, there has been a decline in extension services in rural Kyela, a state attributed to shortage of extension officers and reluctance of some of them to visit rural farmers. Thus, the roles extension officers perform are generally unsatisfactory. Similarly, Msoffe and Ngulube (2016) noted that most farmers are not satisfied with the information dissemination services. The main reasons for the dissatisfaction included inadequacy of information services from extension officers, lack of reliable sources of information, and lack of awareness on the availability of information. In this study, untimely delivery of information was responsible for dissatisfaction among a noticeable proportion of smallholder farmers.

Specifically, smallholder farmers have associated untimely delivery with poor information infrastructure, shortage of extension officers to deliver and exchange information with them, and the costs of information resources such as TV and smartphones as also reported by Ndimbwa et al. (2019) and Mwantimwa (2017). These findings corroborate those by Babu et al. (2012) who noted that unreliability and its untimeliness are major factors undermining smallholder farmers’ satisfaction with provided information. Indeed, inadequate and unreliable agricultural information impede farming activities as Adio et al. (2016) noted. The dissatisfaction with accessed agricultural information has serious consequences on smallholder farmers’ agricultural production. As shown by related studies (e.g., Msoffe and Ngulube, 2016; Ali and Kumar, 2011; Siyao, 2012; Soyemi and Haliso, 2015) satisfaction with information is a key determinant of the extent of productivity primarily because farmers' decisions on production tend to be significantly influenced by the amount of information accessed to upgrade to modern practices that ensure higher yields and income.

Implications of the study

The implications of the present study are diverse. Overall, the study has both theoretical and practical applications, particularly regarding the understanding of smallholder farmers’ access to agricultural information and their satisfaction with it. Theoretically, the findings of this study are an enhancement of the theoretical body of knowledge since they add new details regarding smallholder farmers’ satisfaction with agricultural information and knowledge. On the practical side, the study presents information resource centres, libraries, and other stakeholders with information they can use to delineate the status of agricultural information accessibility and farmers’ satisfaction with it. The findings also provide the Ministry of Agriculture and agricultural institutes with a basis to improve smallholder farmers’ access to and use of agricultural information to enhance agricultural production. Accordingly, the findings are likely to benefit smallholder farmers’ communities by orchestrating the delivery of relevant and timely agricultural information to them hence helping them to boost their knowledge and, subsequently, their production and livelihoods.

Study limitations and further research

Like any other research project, the present study was not immune to limitations. Among the limitations faced was the researchers’ failure to access a sample-frame of smallholder farmers in the selected villages of Kyela district. This hindered the use of simple random sampling to select the study’s sample. As a result, the researchers decided to use convenience sampling to draw the sample. This has limited the generalisability of the study’s findings. Convenience sampling does not yield a representative sample because sample units are only selected if they can be accessed easily and conveniently. In consequence, most members of the target population did not have the likelihood of being drawn into the sample (see also Sarstedt et al., 2018; Baker et al., 2013). Besides, the present study adopted a cross-sectional design that has taken a snapshot of smallholder farmers’ satisfaction with delivered agricultural information rather than a longitudinal research design that could have helped to validate the level of satisfaction and application of the information. In fact, a longitudinal survey has many advantages in advancing knowledge because it allows for more concise and better results as compared to a cross-sectional one (Pampaka, 2021; Cohen et al., 2017; Abrahams et al., 2018; Farrington, 1991).

Thus, future studies aimed to address some of the limitations of the present study to advance knowledge in this area are important. Although previous studies have extensively reported findings on access to and use of agricultural information as a key determinant of agricultural production, the present study reveals satisfaction with the information as another important ingredient for fostering agricultural production. Thus, further studies should be carried out to establish linkages between access to, use of, and satisfaction with agricultural information. Accordingly, long-term follow-up research using a longitudinal design to assess the tangible impact of agricultural information delivered to farmers is necessary. Such studies will further enrich our understanding of the contributions of information to the knowledge economy and, subsequently, to agrarian revolution in the developing world context of Tanzania.

Conclusion and recommendations

Smallholder farmers’ satisfaction with agricultural information depends on the types,relevance, and timeliness of information. In fact, satisfaction with the information is an important determinant of informed and rational decision-making in agriculture. Satisfaction with and utilisation of agricultural information help smallholder farmers to uptake innovative farming techniques which then translate into sustainable production. Therefore, to foster smallholder farmers’ agricultural production, deliberate efforts by the Tanzanian government, non-governmental organisations, and other relevant parties to enhance the farmers’ satisfaction with agricultural information should be made. The stakeholders should start using channels such as demonstration plots, farm field schools, agricultural shows, and farmers’ groups to foster access to and use of agricultural information to enhance satisfaction.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks go to the University of Dar es Salaam and Mozambique-Tanzania Centre for Foreign Relations for material support. Besides, our special thanks go to the University of Dar es Salaam for the research clearance letter that facilitated data collection. We are also grateful to Mr. Elias Mwabungulu for his language and content expertise.

About the authors

Tumpe Ndimbwa is a Librarian at the Mozambique-Tanzania Centre for Foreign Relations (CFR). She has a master’s and PhD in Information Studies from the University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Her teaching and research specialization are library, information and knowledge management, international relations, and diplomacy. She can be contacted at mwakapalila@yahoo.com

Kelefa Mwantimwa is a Senior Lecturer in the Information Studies Unit at the University of Dar es Salaam. He has master’s degree in information studies from the University of Dar es Salaam and PhD in Information Science from the University of Antwerp. Kelefa is a multidisciplinary researcher with more than twelve years of research experience. His research interests are information, knowledge and innovation systems, and ICTs. He has conducted research and published papers in information, knowledge and innovation systems, and ICTs in socio-economic development. His contact address is mwantimwa@udsm.ac.tz

Faraja Ndumbaro is a Senior Lecturer in Information Studies,University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. He obtained his BA degree in political science and public administration and MA degree in information studies from the University of Dar es Salaam and PhD in collaborative learning based information behaviour from the University of Kwazulu Natal, Pietermaritzburg, Republic of South Africa. His teaching and research interests include collaborative information behaviour, application of technology in libraries, management of libraries and information service organizations, and virtual political participation. He can be contacted at ndumbaro.faraja@gmail.com

References

Note: A link from the title or from (Internet Archive) is to an open access document. A link from the DOI is to the publisher's page for the document.

- Adebayo, S., & Oladele, O. (2012). A review of selected theories and their applications to information seeking behaviour and adoption of organic agricultural practices by farmers. Life Science Journal, 9(3), 63-69. https://doi.org/10.7537/marslsj090312.09

- Abrahams, Z., Lund, C., Field, S., & Honikman, S. (2018). Factors associated with household food insecurity and depression in pregnant South African women from a low socio-economic setting: a cross-sectional study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(4), 363-372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1497-y

- Adio, E.O., Abu,Y., Yusuf. K., & Nansoh .S. (2016). Use of agricultural information sources and services by farmers for improve productivity in Kwara State. Library Philosophy and Practice . (http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1456).

- Aina, L. O. (2004). Towards improving information access by semi and non-literate groups in Africa: a need for empirical studies of their information-seeking and retrieval patterns. In T.J.D. Bothma, and A. Kaniki, (Eds.). ProLISSA 2004 Progress in Library and Information Science in Southern Africa: Proceedings of the Third Biennial DISSAnet Conference, Farm Inn, Pretoria, South Africa, 28-29 October 2004 (pp. 11-20). University of South Africa.

- Ali, J., & Kumar, S. (2011). Information and communication technologies (ICTs) and farmers’ decision-making across the agricultural supply chain. International Journal of Information Management, 31(2), 149-159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2010.07.008

- Amah, N. E., Alele, I. O., & Chukwukere, V. C. (2021). Appraisal on information–seeking behaviour of rural women farmers in Jos South Local Government Area, Plateau State, Nigeria. International Journal of Science and Applied Research, 4(1-2), 9-18. (http://www.ijsar.org.ng/index.php/ijsar/article/download/85/80) (Internet Archive)

- Antwi-Agyei, P., & Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H. (2021). Evidence of climate change coping and adaptation practices by smallholder farmers in northern Ghana. Sustainability, 13(3), 1308. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031308

- Armstrong, L., & Gandhi, N. (2012). Factors influencing the use of information and communication technology (ICTS) tools by the rural famers in Ratnagiri Districts of Maharashtra, India. In Proceedings of the Third National Conference on Agro Informatics and Precision Agriculture 2012 (APIA 2012). (pp. 58-63). Allied Publishers Private Ltd. (https://ro.ecu.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1104&context=ecuworks2012).

- Babu, S.C., Glendenning, C.J., Asenso-Okyere, K., & Govindarajan, S.K. (2012). Farmers’ information needs and search behaviors. Case study in Tamil Nadu, India. International Food Policy Research Institute. (IFPRI Discussion Paper 01165). (https://ebrary.ifpri.org/digital/api/collection/p15738coll2/id/126836/download). http://dx.doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.126226.

- Baker, R., Brick, J.M., Bates, N.A., Battaglia, M., Couper, M.P., Dever, J.A., Gile, K.J., & Tourangeau, R. (2013). Non-probability sampling. Report of the AAPOR task force on non-probability sampling. American Association for Public Opinion Research. (https://bit.ly/3taXuvm). (Internet Archive)

- Barakabitze, A.A., Kitindi, E., Sanga, C., Shaban, A., Philipo, J., & Kabirige, G., (2015). New technologies for disseminating and communicating agriculture knowledge and information: challenges for agricultural research institutes in Tanzania. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 70(2), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1681-4835.2015.tb00502.x.

- Berg, B. (2007). An introduction to content analysis. In B.L. Berg, (Ed.)., Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. (pp. 238-267) Allyn and Bacon.

- Brhane, G., Mammo, Y., & Negusse, G. (2017). Sources of information and information seeking behaviour of smallholder farmers of Tanqa Abergelle Wereda, central zone of Tigray, Ethiopia. Journal of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, 9(4), 47-52. https://doi.org/10.5897/JAERD2016.0850

- Choudhury, A. (n.d.). Questionnaire method of data collection: dvantages and disadvantages. Your Article Library. (https://www.yourarticlelibrary.com/social-research/data-collection/questionnaire-method-of-data-collection-advantages-and-disadvantages/64512). (Internet Archive)

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2017). Surveys, longitudinal, cross-sectional and trend studies. In L. Cohen, L.Manion, & K. Morrison. Research methods in education (pp. 334-360). Routledge.

- Creswell, J.W. (2014). Research design: qualitative and quantitative, and mixed methods approach. (4th ed.). Sage publication.

- Daniel, E., Bastiaans, L., Rodenburg, J., Centre, A.R., Schut, M., & Mohamed, J.K. (2013). Assessment of agricultural extension services in Tanzania: a case study of Kyela, Songea Rural and Morogoro rural districts. Internship Report. (http://www.parasite-project.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Elifadhili-2013-Internship-report-final.pdf) (Internet Archive)

- Daudu, S., Chado, S.S., & Igbashal, A. A. (2009). Agricultural information sources utilized by farmers in Benue State, Nigeria. Production Agriculture and Technology Journal, 5(1), 39-48. http://patnsukjournal.net/vol5no1/p5.pdf (Internet Archive)

- Diemer, N., Staudacher, P., Atuhaire, A., & Fuhrimann, S. (2020). Smallholder farmers’ information behaviour differs for organic versus conventional pest management strategies: a qualitative study in Uganda. Journal of Cleaner Production, 257, article 120465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120465

- Diekmann, F. Loibl, C., & Batte, M.T. (2009). The economics of agricultural information: factors affecting commercial farmers’ information strategies in Ohio. Review of Agricultural Extension, 31(4), 853-872. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9353.2009.01470.x

- Case, D.O. (2002). Looking for information: a survey of research on information seeking needs and behaviors. Academic Press.

- Dutta, R. (2009). Information needs and information-seeking behaviour in developing countries: a review of the research. The International Information and Library Review, 41(1), 44-51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iilr.2008.12.001

- Edson, S.A., & Akyoo, A.M. (2021). Implication of quality uncertainty on market exchange: the case of seed industry in Kilolo district, Tanzania. Emerald Open Research. https://doi.org/10.35241/emeraldopenres.13447.3

- Elfil, M., & Negida, A. (2017). Sampling methods in clinical research: an educational review. Emergency, 5(1), e52. https://doi.org/10.22037/emergency.v5i1.15215.

- Elly, T & Silayo, E.E. (2013). Agricultural information needs and sources of the rural farmers in Tanzania: a case of Iringa rural district. Library Review, 62(8-9), 547-566. https://doi.org/10.1108/LR-01-2013-0009

- Elias, A., Nohm, M., Yasunobu, K., & Ishida, A. (2015). Farmers’ satisfaction with agricultural extension service and its influencing factors: a case study in Northwest Ethiopia. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology, 18(1), 39-53. http://jast.modares.ac.ir/article-23-6455-en.html (Internet Archive)

- Farrington, D.P. (1991). Longitudinal and experimental research in criminology. Journal of Crime and Justice, 42(1), 453-527. https://doi.org/10.1086/670396

- Fawole, O.P. (2008). Pineapple farmers’ information sources and usage in Nigeria. Bulgarian Journal of Agricultural Science, 14(4), 381-389. https://www.agrojournal.org/14/04-05-08.pdf. (Internet Archive)

- Food and Agriculture Organization. (2017). The state of food and agriculture: leveraging food systems for inclusive rural transformation. The Organization. https://www.fao.org/3/I7658E/I7658E.pdf. (Internet Archive).

- Fossard, E.D. (2005). Writing and producing radio dramas. Sage Publications. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9788132108573

- Galadima, M. (2014). Constraints of farmers’ access to agricultural information delivery. A survey of rural farmers in Yobe Nigeria. Journal of Agriculture and Veterinary Science, 7(9),18-22. https://doi.org/10.9790/2380-07921822.

- Gunasekera, J., & Miranda, R. (2011). Beyond projects: making sense of the evidence. In D.J. Grimshaw, & S. Kala. Strengthening rural livelihoods. The impact of information and communication technologies in Asia (pp. 133–148). Practical Action Publishing Ltd.

- Kaske, D., Mvena, Z., & Sife, A. (2017). Mobile phone usage for accessing agricultural information in Southern Ethiopia. Journal of Agricultural and Food Information, 19(3) 284-298. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496505.2017.1371023

- Khalil, C.A., Conforti, P., Ergin, I., & Gennari, P. (2017). Defining small-scale food producers to monitor target 2.3 of the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Food and Agriculture Organization. Statistical Division. https://www.fao.org/3/i6858e/i6858e.pdf. (Internet Archive)

- Khatoon-Abadi, A. (2011). Prioritization of farmers’ information channels: a case study of Isfahan Province, Iran. Journal of Agriculture Science and Technology, 13(6), 815-828. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=216807

- Koutsouris, A. (2010). The emergence of the intra-rural digital divide: a critical review of the adoption of ICTs in rural areas and the farming community. In Proceedings, 9th European IFSA Symposium, Vienna, Austria, 4-7 July, 2010 (pp. 23-32). http://ifsa.boku.ac.at/cms/fileadmin/Proceeding2010/2010_WS1.1_Koutsouris.pdf. (Internet Archive)

- Krell, N.T., Giroux, S. A., Guido, Z., Hannah, C., Lopus, S.E., Caylor, K.K., & Evans, T.P. (2020). Smallholder farmers' use of mobile phone services in Central Kenya. Climate and Development, 13(3), 215-227. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2020.1748847

- Kumar, R. (2011). Research methodology: a step-by-step guide for beginners. (3rd ed.) Sage Publications.

- Levi, C. (2015). Effectiveness of information communication technologies in dissemination of agricultural information to smallholder farmers in Kilosa district, Tanzania. (Unpublished master's dissertation). Makerere University.

- Lwoga, E.T., Ngulube, P., & Stilwell, C. (2011). Access and use of agricultural information and knowledge in Tanzania. Library Review, 60(5), 383-395. https://doi.org/10.1108/00242531111135263

- Lwoga, E.T., Ngulube, P., & Stilwell, C. (2010.) Information needs and information seeking behaviour of small-scale farmers in Tanzania. Innovation, 2010(40), 82-103. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC46504

- Lwoga E.T., Stilwell, C., & Ngulube, P. (2011). Access and use of agricultural information and knowledge in Tanzania. Library Review, 60(5), 383-395. https://doi.org/10.1108/00242531111135263

- Magesa, M. M., Michael, K., & Ko, J. (2014). Access to agricultural market information by rural farmers in Tanzania. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Research, 4(7), 264-273. https://doi.org/10.1002/isd2.12134

- Mbwangu, F. (2018). Challenges of meeting information need of rural farmers though internet-based services: experiences from developing countries in Africa. In Proceedings IFLA World Library and Information Conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 24-30 August, 2018. (9 p.) http://library.ifla.org/id/eprint/2195/1/166-mbagwu-en.pdf

- Milovanovic, S. (2014). The role and potential of information technology in agricultural improvement. Journal of Economics of Agriculture, 61(2), 471-485. https://doi.org/10.5937/ekoPolj1402471M